Headlines and Hashtags

Chen Ping on Chinese politics and the missing individual

By David Bandurski — If we tightened the focus on our mental microscopes, dropping through the broad strokes of Chinese history and politics, and through the thicket of foreign aggression — would it then be possible to locate the root of China’s historical weakness in the micro-details of Chinese culture itself, in China’s “cultural genes”?

That may sound like sticky and dangerous territory, but it is exactly where Sun TV chairman Chen Ping (陈平) stood last Thursday evening as he addressed an audience at the University of Hong Kong.

In his talk, “People, Party and Princedom: The Chinese People on the Road to Republicanism,” hosted by the Journalism & Media Studies Centre, Chen Ping made a cultural reading of the nature and history of politics in China, arguing that one of the most fundamental stumbling blocks to China’s social, political, economic and cultural development has been the “lack of respect for the individual, and for the notion of the individual.”

This idea — whose simplicity was perhaps both its virtue and its vice — formed the basis of Chen’s argument that China had been unable to transition from a “princedom,” or junzhu (君主), to a democratic republic in the early 20th century because the concept of the individual had not yet taken root.

Instead, China moved into what Chen characterized as a “transitional phase” between princedom and democracy — a system of “party rule,” or dangzhu (党主).

“We are still in the midst of an age of party rule,” Chen said to his mostly Chinese audience.

And the suppression of the individual, he added, remains a key stumbling block for the future of China’s growth and development today.

In Chinese society, said Chen, individual identity is routinely erased. “What we have in China are roles allocated for us by society (社会分工的角色),” he said.

“If you attend a conference in mainland China, people will open up the session by saying things like, ‘Dear Leaders,’ or ‘Dear Special Guests.’ Everyone has a role, an abstract identity — they are not there as individuals. In Chinese culture, when I look at someone, it may seem that I am looking at a flesh-and-blood human being, but in fact, what I’m looking at is a sign [denoting something else]. I am looking at [the concrete manifestation of] a particular social role.”

Chen explained how he was often referred to at Sun TV as “Chairman Chen,” to which he sometimes jokingly replied: “What? I don’t have a name?”

In Chinese culture, said Chen, the “natural person” has disappeared in a culture of pre-defined roles and identities. “Much to our sorrow, we [Chinese] have lost sight of the individual,” he said.

In Chen’s view, this cultural fact explains why democracy did not take root after the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 and the May Fourth Movement of 1919. While China sought at the time to develop into a democratic republic, which was “all the rage worldwide,” the concept of the individual, the basic foundation of human rights and democracy, had not yet taken root.

“How could a society based on role assignment (分工角色) possibly transform itself [so quickly] into a democratic society?” he asked.

The result, said Chen, was the emergence in China of party rule, or dangzhu (党主).

According to Chen’s reading of 20th century Chinese history, the system of party rule was instituted by Sun Yat-sen, then carried on by Chiang Kai-shek. Finally, said Chen, to a peal of audience laughter, “party rule was perfected by Mao Zedong.”

As China gazed into its own past for something with which it could re-organize society, the only playbook it found was dictatorship (专制). But dictatorship could no longer center upon an emperor who embodied the divine nature of “Heaven” (天). The imperfect solution, said Chen, had been to transition to a system of party dictatorship in which the new Marxist ideology was used to once again suppress the individual.

While Chen did not address the mechanics by which the concept of the individual and individual consciousness is taking root in China today, the assumption was there in his insistence that “party rule” is a necessary “transitional phase.”

“Party rule,” he concluded, “is a preparation for democracy.”

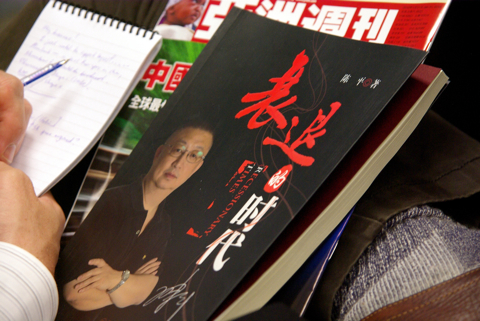

[ABOVE: Published in 2009, Chen Ping’s latest book, Recessionary Times, offers his reflections on China and the recent global economic crisis.]

[Posted by David Bandurski, January 22, 2010, 4:12pm HK]