Ever since President Hu Jintao’s major media policy speech back on June 20, 2008, party leaders have been obsessed with “public opinion channeling,” or yulun yindao (舆论引导), the banner term of what we have called at CMP “Control 2.0.” Unlike the Jiang Zemin-era media control term “guidance of public opinion,” channeling is less focused on suppressing negative news coverage and more concerned with spinning news in a direction favorable to the leadership. As we’ve pointed out, however, this is much more than “spin” — it’s spin with all the advantages of traditional media controls. Trusted party-state media may be encouraged to report breaking news, such as mine disasters, more actively and from the scene, but controls are maintained or tightened for in-depth coverage.

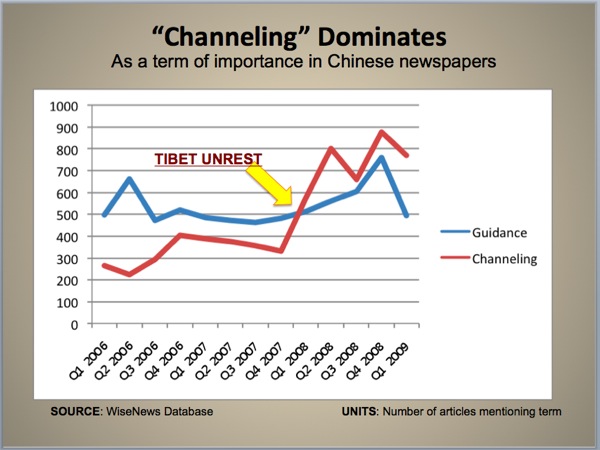

The term “public opinion channeling” in fact rose to dominance before Hu Jintao’s media policy speech in 2008. The crucial turning point was unrest in Tibet in March 2008 and the resulting international public relations disaster for China. Tibet in 2008 has in many ways become the media failure that precipitated the rise of “channeling,” in the same way that widespread protests in the spring of 1989, and the crackdown that followed, were the media failure that prompted the rise of “guidance of public opinion” as the dominant term for almost two decades. In the following graph, I have plotted the number of articles using the term “guidance” or “channeling” in Chinese newspapers from 2006 through to the end of last year.

While some have argued that “public opinion channeling” represents a newfound respect for “news principles” on the CCP’s part, or even a greater openness, the control aspects of the policy remain evident, and it would be naive to suggest the CCP has had a change of heart on information controls. The gains that can be seen in more active reporting of natural disasters, for example, have been offset by stricter control of such practices as “supervision by public opinion,” or media supervision of power. We prefer the term Control 2.0 because it points to the overall advancement of China’s media environment — particularly, the development of the internet and new media — while acknowledging that controls have changed and advanced too.

Fortunately for those who’d like to know more about “public opinion channeling,” new writings on the subject are coming out all the time in China to meet the demand for this must-know policy. The latest is a book by Ren Xianliang (任贤良), currently a deputy propaganda minister in the Shaanxi Province, and it is called The Guiding Art of Public Opinion.

In a recent piece in Guangdong’s Southern Weekend, Chen Bin (陈斌) takes a look at this newly released volume on the policy that is taking the news and propaganda field by storm in China. “It is ordinary for officials to think about public relations, and people naturally hope to receive praise rather than censure,” Chen writes. “But public opinion channeling must not become the covering up of the truth, otherwise the outcome will be the opposite of what is intended.”

The Technique of Public Opinion Channeling: How Officials Can Face the Media

By Chen Bin (陈斌), Southern Weekend

The Xinhua Publishing House recently released a book called The Guiding Art of Public Opinion: How Cadres Can Deal With The Media, written by an official presently serving in the propaganda department. It does not oppose supervision by public opinion, or press supervision, and places its emphasis on the “channeling” rather than the “killing” (封杀) of news reports. It sees [“channeling”] as a raising of governance capability and a beneficial experiment in the art of governing. The shift in focus from “impeding” (堵) to “channeling” tells us that leaders now have greater respect for “news principles” (新闻规律), and this is a welcome change.

However, this book carries with it the danger of being misread . . . [I]f the goal becomes to put a positive spin on negative incidents, then even this so-called public opinion channeling is really about the art of taking tragedies and turning them into triumphs, and the opposite of the intended effect will result.

. . . If negative incidents can give rise to positive outcomes, this is naturally for the good of everyone. The problem lies in the methods that are used to obtain these positive outcomes. Consider the Sanlu poisoned milk scandal [of 2008], in which we saw power acting with negligence and ineffectiveness, and in which the failings of the system were thrown into sharp relief. No matter what methods might have been used [at the time] to soften the impact of this incident on local governments, it would have been difficult to instill confidence in the people. In this case, the best thing was to improve the system and address loopholes, ensuring that the Sanlu scandal never happens again. [These improvements] were the triumph amid the tragedy, and the “positive effect” (正面效果) society was looking for.

To sum up, it is ordinary for officials to think about public relations, and people naturally hope to receive praise rather than censure . . . But public opinion channeling must not become the covering up of the truth, otherwise the outcome will be the opposite of what is intended.