China Newspeak

The Tea Leaves of Xi-Era Discourse

Five years ago, I published an article in Media Digest called “Textual Analysis of the 18th Congress Political Report” in which I listed 10 key terms to focus on to analyze the trends presaged in the report. Prior to this year’s 19th Congress, we took a different approach, compiling a database of more than 300,000 words from the political reports of every Party congress held since the 11th National Congress in 1977. Some of the results around certain keywords in that database can be found in Chinese here.

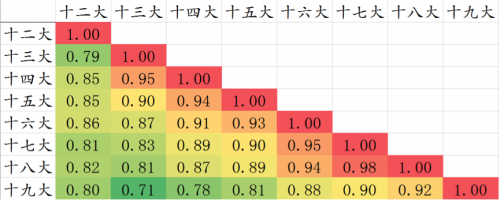

Understanding the textual history of discourse evolution is helpful in analyzing the political report from the 19th Congress. The following is a comparison of the similarity of the reports of the past eight congresses since the 12th Congress in 1982:

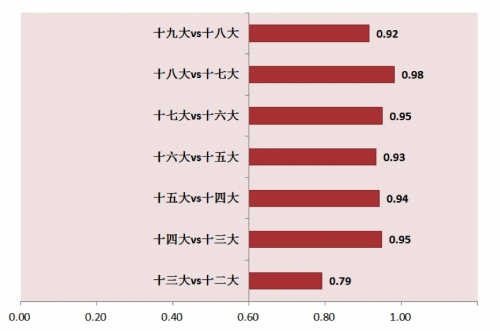

The higher the number on the table, the higher the degree of similarity. The following figure shows the difference between the political report of each national congress and that of the previous congress. The shorter the red column, the greater the difference:

The similarity between the two reports given by Hu Jintao at the 18th and 17th Congresses is 98 percent. The similarity between the two reports given by Xi Jinping at the 19th and 18th Congresses is 92 percent, appearing—among seven numerical values—second from the bottom on the above chart. In other words, there is significant difference in political vocabulary between the 19th and 18th Congresses.

The Xi Jinping Brand

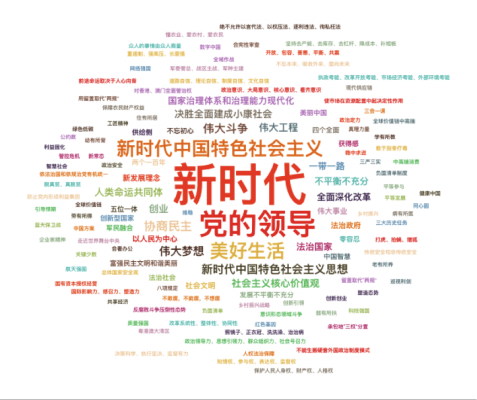

Some scholars believe that the 19th Congress political report was “marked with Xi’s clear brand.” Since Xi came to power five years ago, a large amount of new vocabulary has appeared. These terms were used for the first time in the 19th Congress report, and some of them having never appeared in political documents or in the media before.

Of these the most important ones are “New Era Socialism With Chinese Characteristics” (新时代中国特色社会主义) and “The Thought of New Era Socialism With Chinese Characteristics” (新时代中国特色社会主义思想). The latter is the new banner term determined at the 19th Congress — the term that is meant to mark Xi Jinping’s legacy as Party chief.

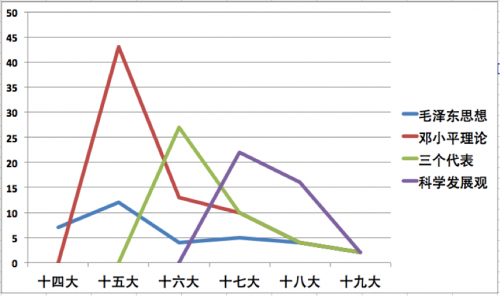

The Communist Party’s banner terms, or guiding ideologies, in the past have been “Marxism” (马克思主义), “Leninism” (列宁主义) and “Mao Zedong Thought” (毛泽东思想)– commonly known together as “Marxism-Leninism-Maoism”–followed by “Deng Xiaoping Theory” (邓小平理论), Jiang Zemin’s “Three Represents” (叁个代表) and Hu Jintao’s “Scientific Outlook on Development” (科学发展观). The last group is commonly shortened in Chinese to “Deng/Three Represents/Science” (邓叁科), though the effect of shortening hardly comes across in English.

Since the 14th Congress, each and every congress would, after presenting its subject, mention the banner language and guiding ideology. The 14th Congress focused on “Deng Xiaoping’s Thought on Building Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.” “Deng Xiaoping Theory” was raised at the 15th Congress. At the 16th, “Deng Xiaoping Theory” and “The Important Theory of Three Represents” were raised. At the 17th and 18th, “Scientific Outlook on Development” was added to “Deng Xiaoping Theory” and the “Three Represents.”

The 19th Congress political report stopped this needless duplication. Xi Jinping said: “The theme of the conference is: Remain true to our original aspiration and keep our mission firmly in mind, hold high the banner of socialism with Chinese characteristics, secure a decisive victory in building a moderately prosperous society in all respects, strive for the great success of socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era, and work tirelessly to realize the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation.”

Xi Jinping no longer speaks of “Deng, Three, Scientific” as guiding the congress. In his report, Xi twice mentioned “Marxism, Leninism, and Mao Zedong thought” and “Deng, Three, Scientific.” In the first instance, he said that the Party, guided by “Marxism, Leninism, and Mao Zedong Thought” and “Deng, Three, Scientific” has worked hard to undertake theoretical explorations and has achieved major theoretical innovations, ultimately giving shape to “New Era Socialism With Chinese Characteristics.”

When he mentioned it the second time, Xi said: “The Thought of New Era Socialism With Chinese Characteristics builds on and further enriches Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the Theory of Three Represents, and the Scientific Outlook on Development. It represents the latest achievement in adapting Marxism to the Chinese context, and encapsulates the practical experience and collective wisdom of our Party and the people. It is an important component of the system of theories of socialism with Chinese characteristics, and a guide to action for all our members and all the Chinese people as we strive to achieve national rejuvenation. This Thought must be adhered to and steadily developed on a long-term basis.” In this passage, the “Deng, Three, and Scientific” formulation is given in the past tense, while “New Era Socialism With Chinese Characteristics” present tense, reflecting its greater currency and relevance.

The relative frequencies of specialized banner terms in the political reports of the 14th to 19th Congresses tell us that prior banner terms have now become history with the 19th Congress. Moreover, when Xi’s new banner term was written into the Party Constitution at the 19th Congress, Xi’s name was added to it: “Xi Jinping Thought of New Era Socialism With Chinese Characteristics.” Jiang Zemin, with his “Three Represents,” and Hu Jintao with his “Scientific Outlook on Development,” were never crowned with their names when their banner terms were written into the Party Constitution. On this count, Xi Jinping has accomplished something extraordinary.

A Forceful Expression of Party Power

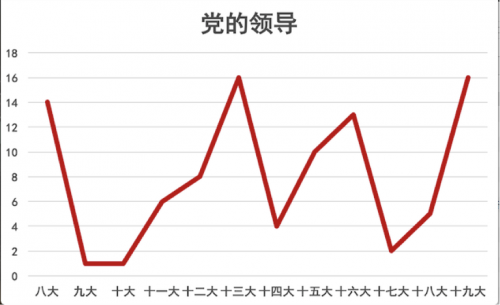

Use of the term “party leadership” reached the highest frequency in the 19th Congress political report compared with previous reports.

Many people who experienced the Cultural Revolution are familiar with Xi Jinping’s phrase: “The Party exercises leadership over all areas of endeavor in every part of the country.” The phrase literally translates: “Party, government, military, society and education, east, west, south, north, the Party governs everything” (党政军民学,东西南北中,党是领导一切的). This is unmistakably the language of the Mao era. The political report to the 10th Congress in 1973 said: “[We] must further strengthen the Party’s unified leadership. The Party exercises overall leadership in the seven aspects of industry, agriculture, business, academics, military, political and Party” (要进一步加强党的一元化领导. 工, 农, 商, 学, 兵, 政, 党这七个方面, 党是领导一切的).

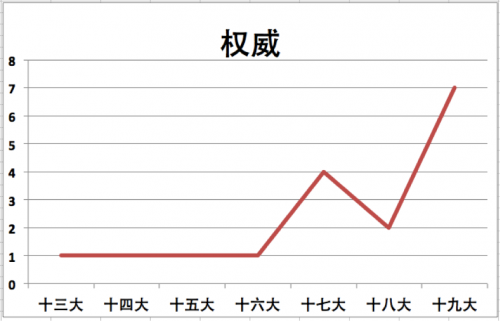

In the 19th Congress political report the word “authority” was also used more frequently than in all previous reports, as we can see here:

“Basic Contradiction” and “Great Struggle”

With ultimate power vested in one person, what is to be done? In addition to the “New Era,” and “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era,” we can add the following frequently-used words that were used more than three times in the report to briefly outline Xi’s blueprint: “Better Life” (美好生活), “Chinese Dream” (中国梦), “prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious, and beautiful” (富强民主文明和谐美丽), “Securing a Decisive Victory in Building a Moderately Prosperous Society” (决胜全面建成小康), “the four comprehensives” (四个全面), “China’s system for governance and capacity for governance” (国家治理体系和治理能力), “Belt and Road” (一带一路), “supply side” (供给侧), “country based on the rule of law” (法治国家) and “sense of fulfillment” (获得感).

The term “unbalanced and inadequate,” which appears five times in the report, comes from an unprecedented formulation:

As socialism with Chinese characteristics has entered a new era, the principal contradiction facing Chinese society has evolved. What we now face is the contradiction between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life. China has seen the basic needs of over one billion people met, has basically made it possible for people to live decent lives, and will soon bring the building of a moderately prosperous society to a successful completion. The needs to be met for the people to live a better life are increasingly broad. Not only have their material and cultural needs grown; their demands for democracy, rule of law, fairness and justice, security, and a better environment are increasing. While China’s overall productive forces have significantly improved and in many areas our production capacity leads the world, our problem is that our development is unbalanced and inadequate. This has become the main constraining factor in meeting the people’s increasing needs for a better life.

This new formulation is worthy of attention as it seems that the ever-growing group who support Mao and criticize Deng and wish to overturn the verdict of the Cultural Revolution will feel very sensitive about this.

In 1956, the 8th Congress declared that “the contradiction between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie in our country has been basically resolved.” The main contradiction in China at that time had been “the contradiction between the advanced socialist system and the backward social productive forces.” As soon as the 8th Congress closed, however, the notion that the contradiction had been resolved was roundly attacked by Mao, and this became one of the crimes alleged against his heir-apparent Liu Shaoqi during the Cultural Revolution.

From the 9th to the 11th Congresses, the “main contradiction” was expressed as “the struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie,” and “the struggle between the socialist road and the capitalist road.” The Third Plenary Session of the 11th Congress cast away “taking class struggle as the key link.” From the 13th to the 18th Congresses, the main contradiction was “between the ever growing demands of material culture and backward social production.” In response to the current situation of China’s economy, the 19th Congress replaced “backward social production” with “unbalanced and inadequate development” and mentioned the growing demands of the people for democracy, the rule of law, fairness and justice.

The latest expression of the main contradiction is certainly closer to Deng and further from Mao. In the Fourteen Perseverances (十四個堅持) offered as part of the idea of “New Era Socialism With Chinese Characteristics” in the 19th Congress report, the third perseverance is offered as “continuing to comprehensively deepen reform.” It emphasizes that China must “continue to modernize China’s system and capacity for governance.”

We must have the determination to get rid of all outdated thinking and ideas and all institutional ailments, and break through the barriers of vested interests. We should draw on the achievements of other civilizations, develop a set of institutions that are well conceived, fully built, procedure-based, and efficiently functioning.

The fourth perseverance is “adopting a new vision for development.” It stresses that “there must be no irresolution in strengthening and expanding the state-owned economy, and encouraging, supporting, and guiding the development of the private sector. We must see that in resource allocation the market plays the decisive role.” These statements are not acceptable to Maoist leftists–the same group that voice extreme dissatisfaction on the internet following the “Decision on Several Issues on the Comprehensive Deepening of Reform” adopted at the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Congress in 2013).

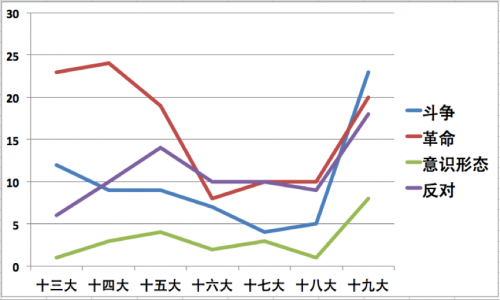

But another key word in the 19th Congress political report will encourage the Maoists. That is the word “struggle,” or douzheng (鬥爭). Xi Jinping said in the report that “to achieve great dreams requires great struggle.” “For the people to confront a great challenge,” said Xi, “they must withstand great hazard and overcome great obstacles and resolve great contradictions.” From the 13th to the 18th Congresses, the word “struggle” was used less and less frequently in political reports. But in the 19th Congress report, it suddenly did an about-face and was used 23 times. Words like “revolution,” “combat” and “ideology” were also used more frequently.

The report also for the time used the term “stability maintenance,” or weiwei (维稳). “Stability maintenance” is shorthand for “the maintenance of stability,” or weihu wending (维护稳定). In the Chinese context, “stability maintenance” sounds much tougher than “the maintenance of stability,” though the subtlety is impossible to detect in English. In the 16th and 18th congress reports, the slightly softer term “the maintenance of stability” was used, but the abbreviated form was not. The 19th congress report praises the effective role of the military in its “counterterrorism stability maintenance.”

The 19th Congress report is a mixture of “left” and “right.” Reading it gives one a sense of contradiction.

One word that never changed as a key term in reports to successive Party congresses was “transformation” (改造), which was always included in the list of “standard words” accompanying reports. But the word did not appear at all in the report to the 19th congress because, for example, phrases like “socialist transformation” (社会主义改造) were also dropped.

Under example of left-right vacillation: The 16th Congress and 18th Congress reports used the term “[we must] never copy the Western political model.” But in the 19th Congress report the words are slightly toned down and modified to say “we cannot copy mechanically and apply indiscriminately the Western political model.”

I always pay close attention to what I call the “deep red discourse”—the frequency of the terms like “Mao Zedong Thought” and the “Four Basic Principles.” In the 19th Congress report, we see these used at their lowest frequency ever. But in the aspects of Party power and struggle, Maoist language does not decreases but rather noticeably increases. This is perhaps one of the key aspects of what “Chinese Characteristics in the New Era” means–namely, the centralization of Party power, strengthening the whole nation, the unifying of will and direction, the suppression of dissent, the elimination of obstacles, and the efficient construction of a beautiful new world.

Expect Cooling of Political Reform

Xi Jinping’s report uses a new term with which we must familiarize ourselves. This is “channeling expectations” (引導預期). These words have profound significance for understanding the Xi Jinping era.

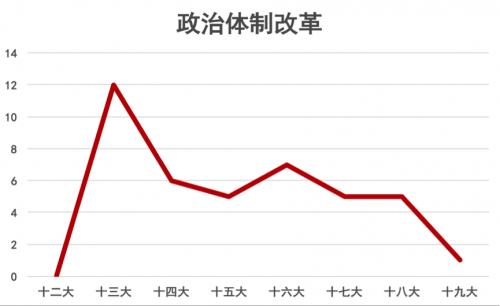

Since Deng’s reforms in the 1980s, Chinese society has always harbored an expectation of political reform. In the 2007 and 2012 China Media Project analyses of the 17th and 18th congress reports, political reform was a key focal point. But the 19th Congress saw major changes.

First, “political reform,” or zhengzhi tizhi gaige (政治体制改革), was removed as a section heading in the political report. From the 13th to the 16th Congresses, “political reform” was always included in a section heading. It was removed in the 17th Congress report, then reappeared in the 18th Congress report. It has once again been removed in the 19th Congress report. The part in the 19th Congress report having to do with political reform is given the more roundabout title: “Perfecting the Peoples’ Control of the Political System, Developing Democratic Socialist Politics.” The term “political reform” appears only once, the lowest frequency since the 13th Congress in 1987.

Correspondingly, the formulation “[The Party] will act within the scope of the constitution and the law” (党必须在宪法和法律範围内活动) was removed from this year’s political report. “The Party must act within the scope of the constitution and the law” was first broached at the 12th Congress in 1982. It continued to be used at the 13th Congress five years later. The 15th Congress in 1997 used the phrase, “The Party leads the People in developing the constitution and the law, and must act within its scope.” The 17th Congress changed this formulation to: “Party organizations at all levels and all Party members must consciously act within the scope of the Constitution and the law.” Finally, the 18th Congress said: “The Party must act within the scope of the constitution and the law.”

All references were removed at the 19th Congress. The alternative wording was: “No organization or individual has the privilege to transcend constitutional law.” As a result of the removal of the subject “The Party,” the weight of this prohibition is obviously reduced as a check on Party power.

Nor do we see in this political report two other phrases related to political reform: “rule the nation in accord with the constitution” (依宪治国) and “governing in accord with the constitution” (依宪执政). These two expressions were coined by Xi when he first came to power. On December 4, 2012, commemorating the 30th anniversary of the current constitution, Xi stated: “Ruling the country in accord with the law first means ruling the country in accord with the constitution; the crux of governing in accord with the constitution is governing in accord with the constitution” (依法治国首先是依宪治国,依宪执政关键是依宪执政).

In 2014, this wording was removed from a Central Propaganda Department compilation called Collection of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s Important Speeches. In commemorating the 60th anniversary of the National People’s Congress in September 2014, Xi Jinping used the two slogans once again. But in the past two years, the slogans have rarely appeared in the People’s Daily. The 19th Congress report referred to “constitutional supremacy,” and even referred to the promotion of “constitutional review.” But it didn’t mention “ruling in accord with the constitution” or “govern in accord with the constitution.” After the 19th Congress, these two terms may be consigned to long-standing limbo.

Obviously, what the authorities hope is to put to rest the hopes of some that talk of “governing in accord with the constitution” might mean institution of “constitutionalism” in China. They want to cool off expectations for political reform, and hinder any limitation on political power or checks and balances. This is in direct opposition to the principle that guided Deng’s notion of political reform in the 1980s, the need to avoid “over-centralization of authority.”

(Zheng Xin served as data editor for the above study).