By QIAN GANG

Keyword: intraparty democracy (党内民主)

On May 14, 2012, an editorial appeared in China’s official People’s Daily newspaper arguing that the country had made “immense progress” on political reform. At the same time, the editorial resolutely shut the door on the idea of a multiparty political system in China. Even as China “actively and steadily promotes” political reform, it said, the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party must be upheld. Moreover:

. . . [We] resolutely will not imitate Western political forms. Only by respecting [our country’s] national circumstances, and by proceeding step-by-step in an orderly way, will we be able to create new Chinese miracles, constantly reaping new self-confidence for our people.

If the idea of competing political parties is left out in the cold, is there any sense in talking about “democracy” at all? Yes, say many Party leaders. And what they advocate are more mechanisms for shared decision-making within the ruling Party itself, what is known as “intraparty democracy,” or dangnei minzhu.

The phrase “intraparty democracy” was in fact a hot watchword in the political report to the 17th National Congress in 2007. But like many Party watchwords, “intraparty democracy” has run hot and cold through history.

At the 9th and 10th national congresses, held during the Cultural Revolution (and the height of power concentration in the hands of Mao Zedong), the phrase disappeared altogether. The phrase appeared three times in the political report to the 11th National Congress in 1977, following the end of the Cultural Revolution, a return to levels actually seen two decades earlier at the 8th National Congress. From the 12th National Congress in 1982 to the 16th National Congress in 2002, the term did appear, but was used only rarely. In these five political reports it emerged 1, 2, 2, 1, and 2 times respectively.

Against this background, the phrase’s showing in the 2007 political report was remarkable. The term popped up five times in a single breathless utterance, as President Hu Jintao said:

. . . [We must] actively advance the building of intraparty democracy, working hard for unity and solidarity within the Party. Intraparty democracy is an important guarantee in strengthening the vitality of the Party, and firming up the Party’s unity and solidarity. [We must] expand intraparty democracy in order to set people’s democracy in motion, furthering harmony within the Party in order to advance harmony in society. [We must] respect the principal status of Party members, ensure the democratic rights of Party members, promote openness of Party affairs, and create the conditions for democratic discussion within the Party. [We must] improve the Party’s national congress system, instituting a system of fixed tenure for delegates to the Party’s national congress, and selecting delegates on a trial basis from a number of counties (cities, districts) for a permanent Party congress system.

Throughout the Party’s history there have been voices calling for an expansion of “democracy” under a single-party system, regarding this as a safe and reliable way of reform. In offering this long grocery list of Party reforms in his political report in 2007, Hu Jintao endeavored to use intraparty democracy as a wedge to promote further reform. But even this is not an easy road.

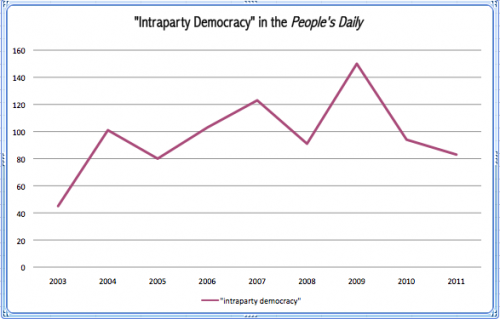

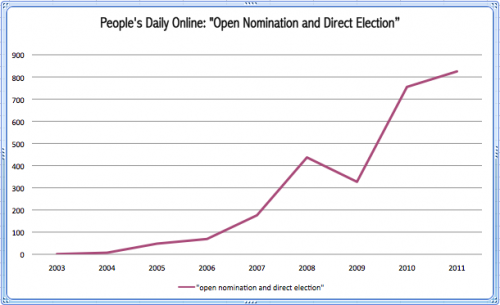

The above graph plots usage of the term “intraparty democracy” in the People’s Daily since 2003, reflecting fluctuations of the term within central-level Party media.

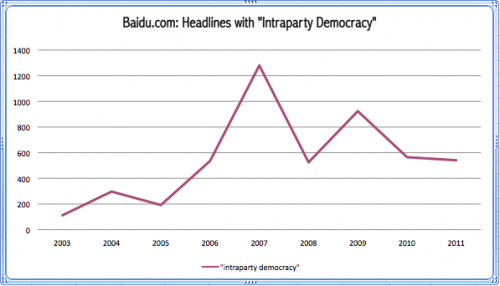

The second graph above shows the frequency with which the term “intraparty democracy” was used in Chinese news media more generally. The original data were obtained from the Baidu.com news search engine. The two data sets do not entirely match up, but we can see that the peaks and lows do correspond, with rising usage in 2004, 2007 and 2009, and falling usage in 2005, 2008 and 2011.

The rise in 2007 is the most robust, reflecting the more prominent role the term played at the 17th National Congress that year and a general expectation across media that intraparty democracy might make advances. The situation in 2009 is quite different, with a strong showing for the term in the People’s Daily but much weaker use of the term across the media as a whole.

Intraparty democracy basically means shutting the door and promoting democracy inside — it does not entail reforms directly impacting Chinese society at large. But the space within the room, so to speak, is in fact extensive. There are more than 80 million Chinese Communist Party members in China, a Party population roughly equal to the population of Germany. If serious steps were taken to promote “democratic” decision-making within this subpopulation of Chinese, this would greatly advantage China as a whole.

[ABOVE: A door in China, photo by Gill Penney posted to Flickr.com under Creative Commons license.]

The problem is that so far the Chinese Communist Party’s talk on intraparty democracy is just that, talk — at least where the fundamental issues are concerned. Are the conditions there for more “democratic discussion” within the Party? It certainly does not seem so when even China’s premier, Wen Jiabao, is censored by the Central Propaganda Department when he talks about political reform. Are the Party’s affairs handled openly? Ahead of this year’s 18th National Congress, speculation has run rife over possible personnel changes within the Party, and Party members are as much in the dark as anyone else. Nothing at all has been done to experiment with a permanent tenure system for congress delegates, an idea that has come up again and again in talk about intraparty democracy.

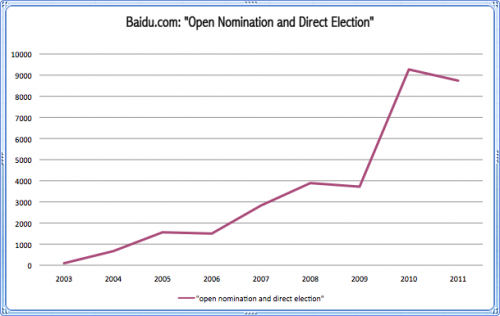

The only apparent action is happening at the grassroots level, where there is purportedly experimentation in certain areas with direct election of Party officials. After he took office, Hu Jintao encouraged a number of places in China to organize experiments in the direct election of grassroots Party officials. One of these places was in Jiangsu province, where the provincial Party secretary, Li Yuanchao, first experimented with “open nomination and direct election,” or gongtui zhixuan (公推直选), between 2002 and 2007.

Gongtui zhixuan is one method of reforming the mechanisms by which leaders are chosen for official posts, a limited decentralization (or letting go) of the Party’s power to exercise control over its own cadres. The word gongtui, which means roughly “mutual nomination,” refers to the method by which candidates emerge.

Formerly (and of course this is mostly still the case), candidates were simply appointed by their Party superiors. Now, in addition to candidates recommended by superiors, Party members can jointly or individually recommend candidates, and city residents or villagers can send representatives to take part in the nomination process. Zhixuan, which means “direct selection,” refers to a process by which a general meeting of Party members or a congress of Party delegates directly elects a candidate for a post from among the nominees.

At the 17th National Congress in 2007, Li Yuanchao, the Jiangsu leader who had experimented with “open nomination and direct election” at the grassroots level, was himself promoted to the Politburo and made head of the Organization Department of the Chinese Communist Party, the body within the Secretariat that handles personnel decisions. From this position he more actively promoted “open nomination and direct election” as a means of making strides in the development of intraparty democracy.

The Fourth Plenary Session of the 17th Central Committee in 2009 said the Party should “promote a method combining open nomination by Party members and the masses and nomination by Party organizations in order to gradually expand the scope of direct election of the leadership groups of grassroots Party organizations.” In 2009 and 2010, China’s media reported actively on these proposed reforms.

By the summer of 2010, “open nomination and direct election” was reportedly being practiced “across the board” in the city of Nanjing, where Li Yuanchao had previously served as Party secretary. This meant, in theory, that all leaders of Party branches in urban neighborhoods and rural villages in this jurisdiction had emerged through this process of open nomination and election. Chinese media called this a “new advance in democracy.”

[ABOVE: A cover of China Newsweek in June 2010 carries the bold headline: “A New Advance in Democracy.”]

“Open nomination and direct election” quickly spread to other regions. In Shenzhen, a deputy provincial level city just across the border from Hong Kong, this method was used even in the selection of delegates to the local Party congress as well as members of the consultative conference, a nominal advisory body made up of representatives from various parties and mass organizations. In a development much touted by the media, Ma Hong, a 42-year-old accountant who had nominated himself as a candidate, was successfully elected as a Party delegate in Shenzhen, becoming the first such case in the country. Ma was dubbed the “black horse,” a play on his surname (“ma” means horse).

[ABOVE: Guangzhou’s Southern Metropolis Daily reports on the election of Ma Hong, the “black horse,” as a delegate to the local Party congress in Shenzhen in 2010.]

“Open nomination and direct election” has not yet been formally promoted nationwide in China as the method of handling Party personnel arrangements, one important reason being that it requires amendment of the Party Constitution. But it’s clear from news reports since 2009 that the method has already spread to many places in China.

I wrote in the Hong Kong Economic Times back in 2010: “The 18th National Congress in 2012 is just two years away, and it’s difficult to say whether open nomination and direct election will, in the next two years, be promoted at the level of county Party secretary appointments. However, it is not inconceivable that open nomination and direct election could be practiced to some extent in the selection of provincial Party congress delegates, and even perhaps for national congress delegates.”

The facts over the past two years have shown that I vastly over-estimated the potential for progress on intraparty democracy. So-called intraparty democracy remains confined to the grassroots, to the lowest levels of the Party’s vast bureaucracy, and any progress beyond this has been difficult.

A number of issues related to intraparty democracy are in fact of greater urgency and importance. These include:

1. Checks-and-balances on the powers of decision-making, administration and monitoring (an issue I addressed here).

2. “Fixed tenure” for the national congress.

3. “Differential election” within the Party’s national congress.

The Party notion of “differential election” or cha’e xuanju (差额选举), is a strange concept to grasp, and for readers from democratic countries it may even verge on the ludicrous. But in China, the so-called ”differential ratio,” the ratio of open seats to candidates, is taken seriously as a democratic measure. Essentially, it refers to the ratio of candidates for official posts to the number of posts actually available. In most democratic countries, ideally you would have a ratio of at least 100 percent before you could talk about democracy at all — which is to say, you have at least two candidates for any given position, 100 percent more candidates than positions available.

From the 14th National Congress in 1997 to the 16th National Congress in 2002, the ratio was 10 percent. That means 110 candidates were nominated for every 100 positions. Delegate spots were subject to competition between multiple candidates in at most 10 cases, with delegates to be chosen by Party electors (there could also have been more than 2 candidates for a spot).

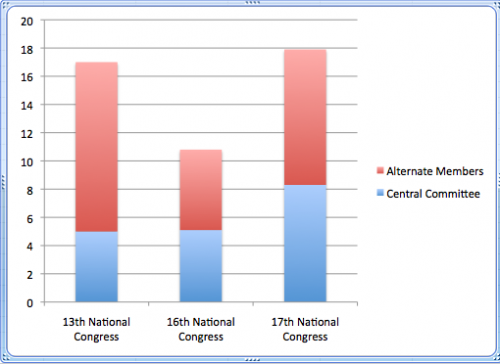

At the 17th National Congress in 2007, much was made in official media about the new ratio of 15 percent (115 candidates for every 100 spots). And at this year’s congress the rate is supposed to surpass 15 percent. The highest rate in the Party’s history was set back at the 13th National Congress in 1987, where one out of five delegate positions were contested.

We can also talk about the “differential rate” in selection of candidates for the Party’s Central Committee, the group of around 350 members selected by the national congress, as well as alternative committee members. Here is a chart showing rates for three congresses since the 1980s.

[ABOVE: “Differential rates” for Central Committee members and alternates for three national congresses.]

What will these differential rates look like for the 18th National Congress? More importantly, will differential election be applied at all to the Politburo, that more elite group of 20-odd Party officials who wield the most political power in China? Never in the Party’s history have these elite positions been left to an intra-party elective process.

There is little doubt that we will continue to see the watchword “intraparty democracy” at the 18th National Congress, but the above three issues are critical ones that the 18th National Congress would have to grapple with if any meaningful progress is to be made. We will have to wait and see how the Party deals with them, if at all. At the same time, we should pay attention to whether the 18th National Congress significantly extends the scope of experiments in the reform of grassroots appointments for Party organizations. For example, will “open nomination and direct election” be more formalized as a model and promoted?