Headlines and Hashtags

Don’t Flaunt It

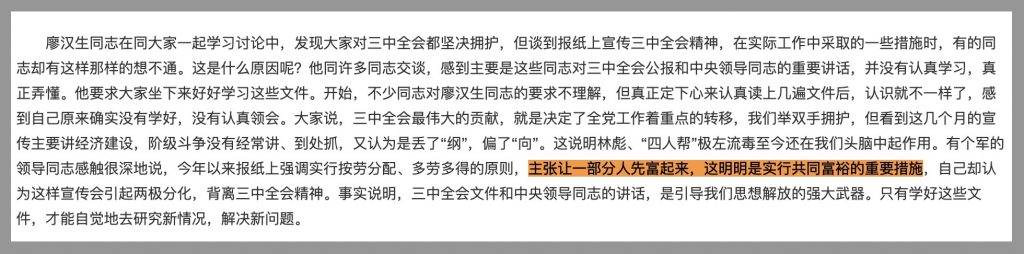

A generation ago China’s drive for economic growth and wealth creation could be summed up in Deng Xiaoping’s famous injunction to “first let a few get rich” (让一部分人先富起来), a formula that became simplified early on with the phrase “to get rich is glorious” (致富光荣). But these days, as Xi Jinping has insisted that the Chinese Communist Party must now close the gap and pursue “common prosperity,” getting rich, or being rich, can be a mark of socio-political shame.

On Chinese social media, this ethos of shame has lately centered on the phenomenon of “wealth flaunting,” or xuanfu (炫富).

Since the Cyberspace Administration of China launched its internet cleanup campaign back in May this year, social media platforms have been working overtime to comply with the broad demands of authorities, regulating content related to fandom culture, online gaming and other areas of priority for the CAC, pushing for a “clean and clear” (清朗) online space. “Wealth flaunting” has been one of a number of areas of focus.

Last week, the social media and e-commerce platform “Xiaohongshu” (小红书), known in English as “Little Red Book” or sometimes simply as “RED,” publicly announced the results of its internal campaign to combat “wealth flaunting,” or xuanfu (炫富), within its online community. RED is a platform where users post on a variety of topics such as food, fashion, travel and lifestyle.

According to RED’s announcement, the platform’s efforts over the past six months to “combat wealth flaunting” (抵制炫富) have resulted in the deletion of 8,787 “wealth-flaunting records in violation of regulations” (炫富类违规笔记). Fines were reportedly imposed by the platform on 240 accounts for related violations.

Interestingly, RED also reported that it had upgraded its algorithmic model for spotting posts that flaunt wealth (炫富识别的算法模型), offering a glimpse at how platforms are directly involved in creating and deploying technical solutions to achieve the objectives defined by the CCP and the CAC. The goal of RED’s upgraded algorithm model is to detect and remove wealth-flaunting content more quickly.

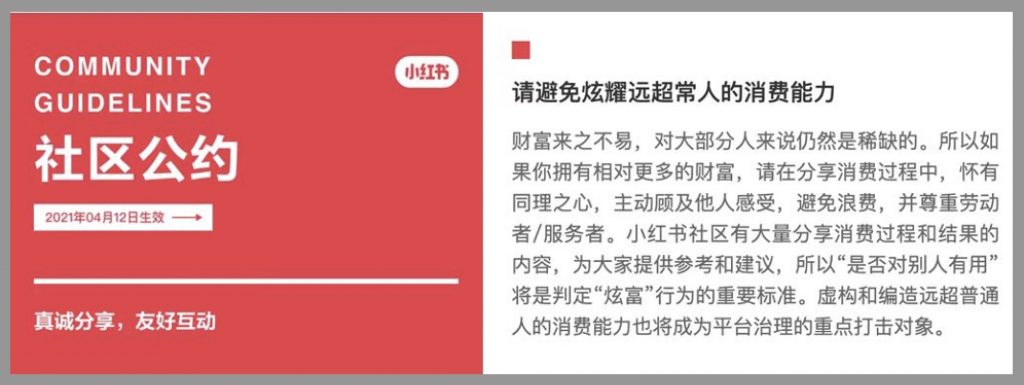

Back in April 2021, before the Chinese internet cleanup campaign was formally launched by the CAC, RED released community guidelines (社区公约) that defined “avoiding showing off your spending power” and “whether [content] is useful to others” (是否对别人有用) as important criteria in determining whether users’ posts should be shared. The guidelines also mentioned “respecting laborers/service providers” and “avoiding waste” as values to be upheld.

Online influencers have also joined the anti-wealth flaunting campaign by posting related content on RED. “Jassie” (杰西学姐Jassie), an influencer who shares career advice on the platform, wrote that such content is harmful to people of all ages, generating anxiety in adults, and implanting “incorrect” values, such as vanity, the temptation to take shortcuts, and the need to constantly compare oneself to others.

Another online influencer, “HR Brother Hong” (HR小弘哥), posted on RED that ostentatious displays of wealth were a vice, creating the illusion that all users on RED are prosperous, even though this is far from the truth. Echoing Xi Jinping’s recent pronouncements on “common prosperity” (共同富裕), “HR Brother Hong” emphasized that pursuing this goal – meaning closing the gap between rich and poor – is more important than chasing fame and affectation.

It is interesting to note that in fact the earliest mentions of Deng Xiaoping’s phrase “first let a few get rich” in the 1970s were closely associated at the time with the phrase “common prosperity.” For example, the first mention of “first let a few get rich” in the People’s Daily, appearing on May 28, 1979, was followed immediately by the words, “this is clearly an important measure in bringing about common prosperity.”

Back in May this year, the CAC directly addressed criteria for assessing wealth-flaunting content as part of its internet cleanup campaign. Zhang Yongjun (张拥军), chief of the CAC’s information management bureau, said during a related meeting: “How do we tell if content is simply sharing [details about] life, or actually showing off wealth? The standard here is to look at the dissemination effect of the content,” he said. “It depends on whether the dissemination of the content encourages people to live a positive and healthy life, or whether it instead triggers people to resent the poor and pursue lives of luxury, seeking ease and comfort without working.”

Zhang’s remarks clearly underscored the desire of the CCP to address the social and political impact of the growing gap between rich and poor in the country.

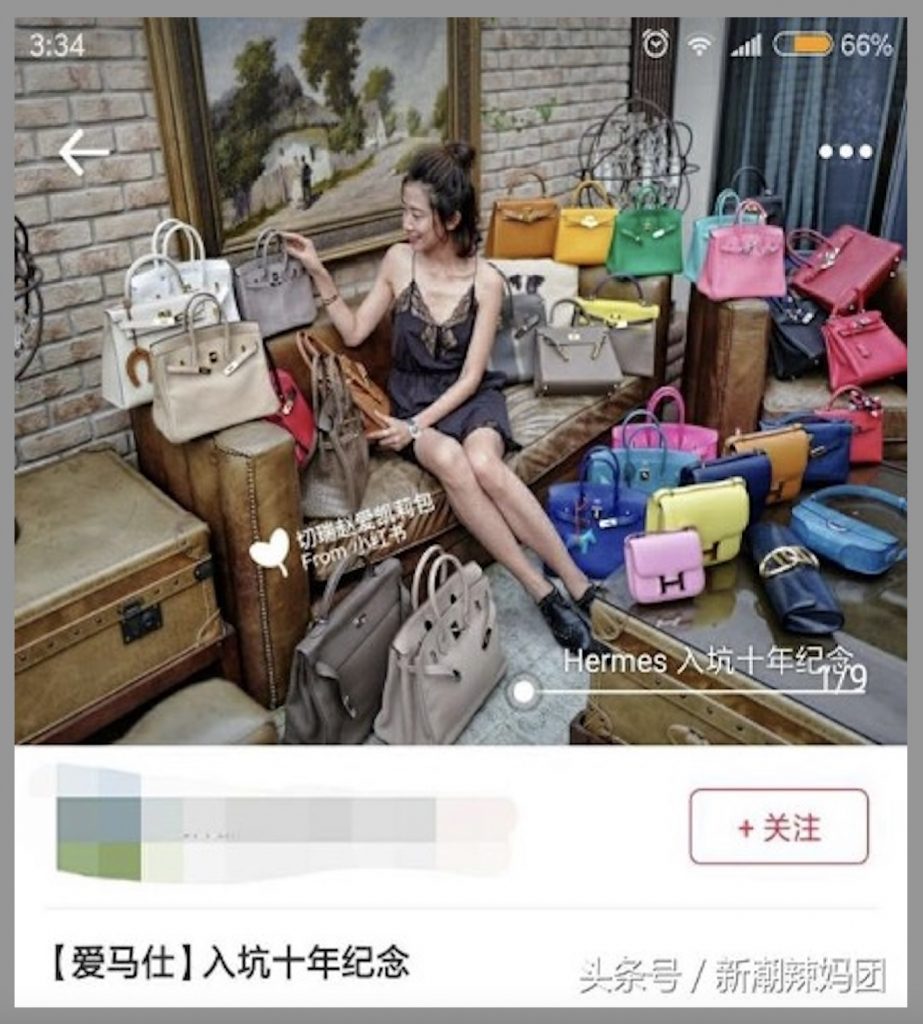

RED has been associated through much of its history – it was launched in June 2013 – with the sharing of content about luxury goods and extravagant lifestyles, an approach that has gained the platform a loyal following. There is a saying in Chinese social media that you can never know how rich Chinese people are until you see them on RED, showing off their latest Hermes bag, their newly-purchased Maserati, or the new house their parents bought for them.

The campaign on RED has been reported by various media in China, and shared widely on Weibo. Many netizens, however, have voiced discontent about the new measures. In the comment section under a related report by China Daily, some refused to support RED’s deletions of wealth-flaunting content. “Deleting all those wealth-flaunting posts and accounts doesn’t mean erasing the wealth gap in China,” wrote one user.

“This is unnecessary,” another wrote. “I can’t afford these products and lifestyles, but can’t I just scroll through the app and see how other people are enjoying such things?”