For anyone with an enduring relationship with China, the stock phrase “5,000 years of Chinese civilization” (中华文明五千年) sits somewhere between familiarity and semantic satiation. And while historians may question that number — which includes the rule of legendary god-kings — as well as the assumption China’s history has been uniquely continuous, there can be little doubt that Chinese today are the inheritors of an ancient and magnificent civilization.

Perhaps that is why, when Xi Jinping proposed the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI) in March, the word at its center raised few eyebrows. But the same cannot be said about “Xivilization,” a portmanteau of “civilization” and Xi’s name coined by the nationalist Global Times tabloid for a new series promoting the GCI.

“Xivilization” is yet to catch on outside the pages of the Global Times. But it may be the pithiest way suggested so far to capture the real assertions being made behind the scenes of Xi’s GCI.

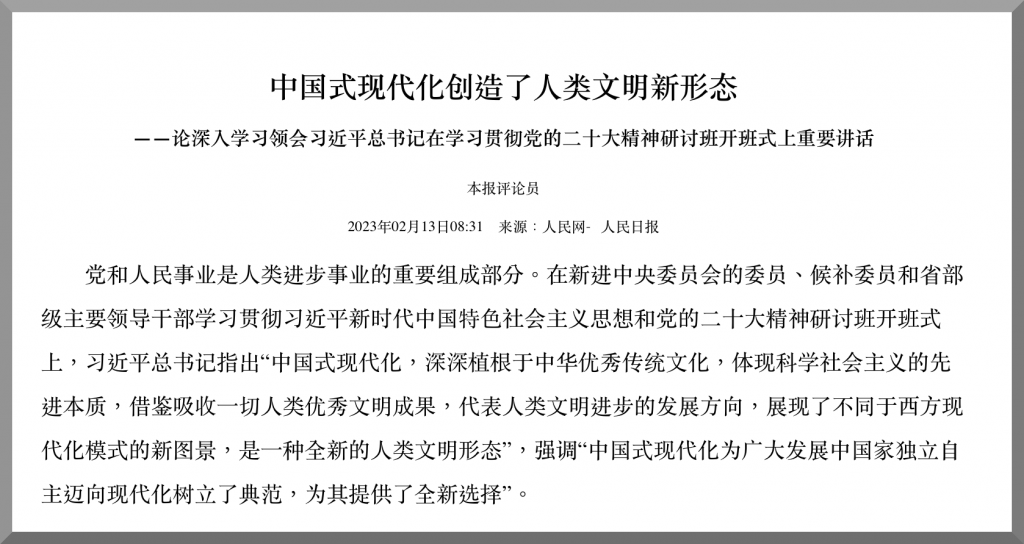

In his speech pitching the GCI to the leaders from political parties from around the world, Xi said “the Chinese Communist Party is committed to promoting the progress of human civilization,” and called Chinese-Style Modernization — another Xi neologism — “a new form of human civilization.” Chinese-Style Modernization, a piece in the Party’s flagship theoretical journal gushed, “represents the developmental direction for [all] human civilization.”

Proclamations like these make it clear that Xi Jinping is no longer considered merely an inheritor or even protector of a great civilization, but the creator of one, too.

‘Civilization’ Comes to China

Despite the long history of civilization in China, the history of the word “civilization” itself is surprisingly short. Like the Chinese for “telephone” or “constitution,” the word for “civilization” in Chinese, wenming (文明), acquired its current meaning through the Japanese translations of European texts made during the island nation’s drive to learn from West during the Meiji-era (1868-1912).

Even then, however, “civilization” and the idea it represented were new to most Europeans as well. When it entered the English lexicon from French it met with stiff resistance from Samuel Johnson, who argued, in compiling his dictionary of the English language, that the word “culture” was perfectly sufficient. What Johnson had failed to grasp, however, was something Chinese thinkers had entertained for centuries. “Civilization” did not merely denote “culture” (wenhua 文化) but a particular, higher stage of culture: one that is more technologically and socially advanced and that crushes other, inferior cultures that stand in its way.

Every nation has culture — only a few have civilization.

In a way, this dynamic was hardly new to the territories we today know as China. As far back as the Tang dynasty (618-907), insulting epithets were being lobbed at those who did not conform to Confucian elites’ criteria for “civilization,” such as having a written language and walled settlements and practicing agriculture. Despite conquering Taiwan in 1683, the Qing dynasty (1644-1912) chose not to govern most of the island until the twilight of their reign, since the territories still dominated by indigenous Taiwanese were considered “beyond civilization” (化外).

Despite the long history of civilization in China, the history of the word “civilization” itself is surprisingly short.

This, however, points to what differentiated these historical and contemporary conceptions of civilization. As Chinese empires expanded and people in frontier territories acquired cultural characteristics, the process of becoming Chinese was equated with becoming civilized. Although China already had words that conveyed the notion of civilization, they were all, as historian Wang Gungwu notes, Sinocentric — the idea of a universal ideal of civilization was a much later import.

The modern reinvention of wenming changed everything. It posited the idea that one could produce a single set of criteria for “civilization” for all of humankind. And, most unsettlingly, it raised the specter that the Chinese themselves might be “civilized” by militarily— and perhaps even culturally — superior outsiders.

The Four Civilizations

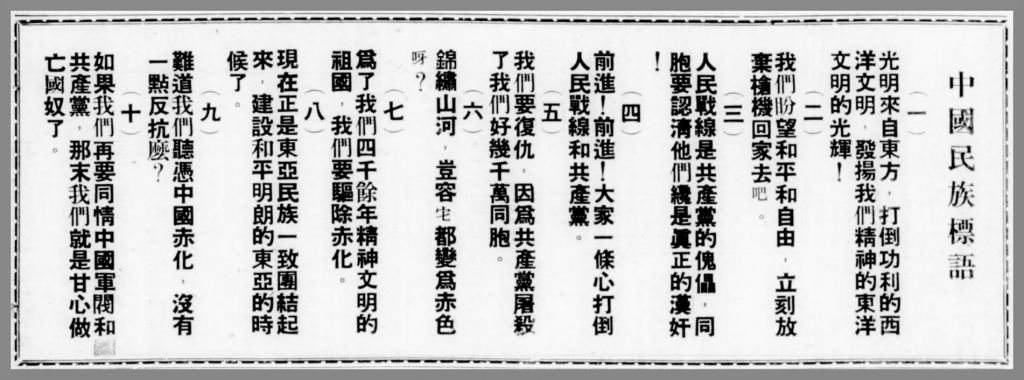

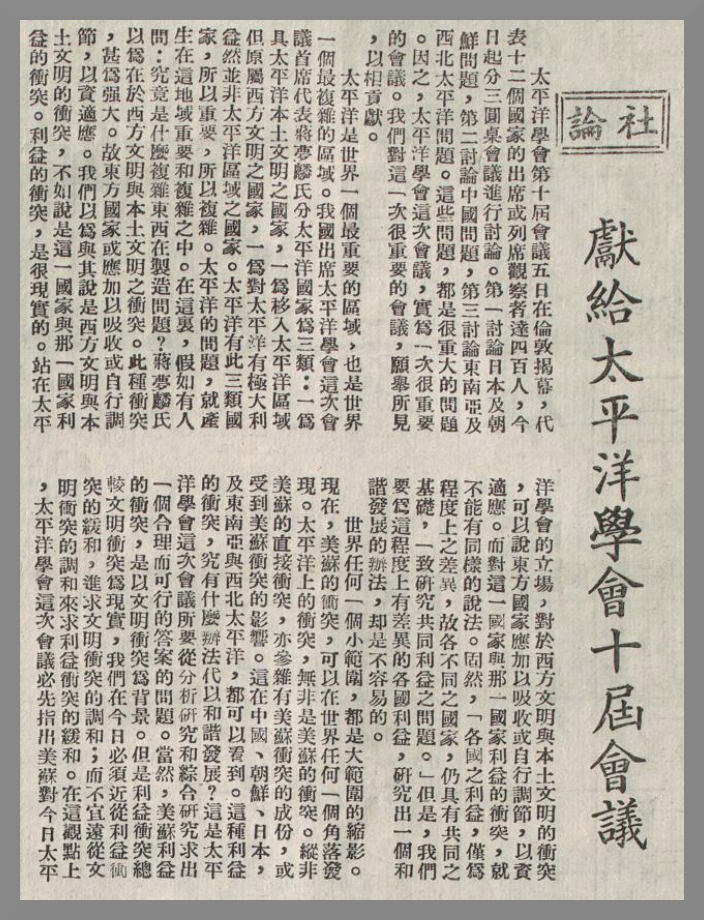

Throughout the Republican Era (1911-1949), debates about civilization spilled across the pages of the young nation’s newspapers. Commentators described a “clash of civilizations” (文明衝突) that characterized the fraught relations between China and Western countries and proposed that there were two opposing forms of civilization: the material and the spiritual.

China boasts a “developed spiritual civilization,” we read in Awakening (覺悟), a supplement to the Kuomintang-founded Republic of China Daily (國民日報), while the West is a “developed material civilization.” This duality reflected the paradigm of “adopting Western knowledge for its practical uses while keeping Chinese values as the core” (中體西用) favored by late-Qing reformers.

This material-versus-spiritual civilizational discourse, so in-vogue in the pre-war decades, made a dramatic comeback in the post-Mao Reform and Opening-up era. But instead of pitting “the East” and “the West” against one another, it put forward the spiritual and material as two parallel tracts running within a single civilization.

In order to achieve “balanced development” (平衡的发展) as his market reforms pushed China further and further from Marxist orthodoxy, paramount leader Deng Xiaoping resurrected the binary framework of the “Two Civilizations” (两个文明): Material Civilization (物质文明) and Spiritual Civilization (精神文明). The former represented the improving living conditions of the people and the latter their allegedly faltering moral character. To reach a positive relationship between the two was to reconcile capitalist development with Communist doctrine.

Deng’s successor, Jiang Zemin, eagerly embraced the notion of spiritual civilization. But whereas Deng had grounded the term in socialist ideology, Jiang festooned it in the cultural nationalism that was promoted in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square crackdown to bolster regime legitimacy. “Spiritual civilization” became a byword for traditional cultural values, an avatar for the emerging struggle between globalization and nationalism in the age of China’s 2001 accession to the World Trade Organization.

At the CCP’s 16th national congress in 2002, however, Jiang broke the neat “two civilization” duality to introduce a third civilization: “Political Civilization” (政治文明). The construction of a “Socialist Spiritual Civilization” (社会精神文明) was also declared a precondition for achieving the overarching goal of a “well-off society” (小康社会). The equation was knocked off-balance but it raised hopes for deepening political reform, since the idea that political systems had to be “civilized” suggested room for reflection and improvement for the Party itself.

Soon “civilization” was everywhere, at no time more ubiquitous nationwide than in the lead-up to the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing and the 2010 Shanghai World Expo. Up and down the country, propaganda posters lined the streets extolling “civilized cities,” “civilized districts,” “civilized work units,” and “civilized households.”

The mania for national self-civilization exemplified how “civilization” was understood to be both a human grouping as well as a historical process, and also how the Communist Party sought to rebrand itself from a revolutionary vanguard to an elite circle. The CCP, wrote Nicholas Dynon, was “recreated as a party which finds its legitimacy not on the basis of class credentials but on the basis of civilizational superiority.”

Talk of building a “Socialist Spiritual Civilization” thinned out under Hu Jintao, but the “civilizing” mission lived on — both in a domestic imperative to raise population “quality,” aimed primarily at ethnic minorities and rural migrants, and a growing sense that Chinese entrepreneurs, officials, and workers abroad were taking up the torch of the global modernizing mission once championed by Euro-American powers. Pál Nyíri observed how Beijing’s narratives “combine trade, investment, labor export, migration, and development aid with distinctly civilizational overtones.” And while the desire to “civilize” its subjects characterizes the modern nation-state in general, Nyíri notes that, unlike the Western colonial case, China’s internal and external “civilizing” missions are being run in tandem.

Considering Hu’s concept of the “harmonious society” (和谐社会), his addition of a fourth, “Social Civilization” (社会文明) is unsurprising. Like the harmonious society, “Social Civilization” was an attempt to paper over the widening divisions in Chinese society, between the winners and losers of the country’s breakneck industrialization and urbanization. While Hu’s concept lacked the rhetorical strength or staying power of earlier “civilizations,” it showed how deeply entrenched and yet endlessly malleable the idea of “civilization” had become in the political life of the CCP.

Every leader was now expected to create their own “civilization” — and they could attach it to virtually anything they wanted.

Age of Xivilization

When Xi Jinping’s transition to power began in 2012, China was still riding a wave of awestruck international perceptions built around the notion that the emerging superpower was something greater than a nation — it was a civilization.

Throughout the 2000s, Chinese translations of Samuel P. Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order filled bookstore shelves and street side carts flogging bootleg printouts. The American scholar’s theory that the wars of the future would pit loosely-defined “civilizations” rather than nations against one another found an eager readership in the People’s Republic, and neatly dovetailed with the idea of China as a “civilization-state” popularized in Martin Jacques’ When China Rules the World (2009) and the work of Fudan University political scientist Zhang Weiwei (张维为).

A little over a decade later, this zeitgeist has not aged well. The notion of the People’s Republic as a singularly harmonious and tolerant “civilization-state” seems farcical in Xi Jinping’s China: one that is increasingly nationalistic, outwardly aggressive, and inwardly repressive.

Jacques’ argument that China possesses an unparalleled capacity for plurality hinged on the existence of the “one country, two systems” formula preserving Hong Kong’s freedoms and autonomy. That equation no longer meaningfully exists in Xi’s China, which has crushed the territory’s civil society and its free press, effectively banned protests, removed any meaningful elections, and jailed or exiled nearly every prominent member of the political opposition.

Zhang’s big idea, meanwhile, was evinced by China’s benevolent treatment of its “ethnic minorities” — questionable even before Xi’s campaign of mass incarceration for Uyghurs and other non-Han peoples in the far-west — and frictionless relations with its neighbors, which now spew sparks regularly as Beijing presses its claims in the South China Sea and elsewhere.

Every leader was expected to create their own “civilization” — and they could attach it to virtually anything they wanted.

But where Xi has torn down previous leaders’ civilizational pillars, he is now building anew. While he has yet to formally add a fifth civilization to the pantheon built by his predecessors, his “New Form of Human Civilization” (人类文明新形态) effectively constitutes just that.

Red Flag (红旗文稿), a bi-monthly magazine published by the CCP’s flagship journal Qiushi, ties Xi’s thought to previous “civilizations” (although retconning the contributions of lesser leaders Jiang and Hu), proclaiming that it “harmonizes Material and Spiritual Civilization.” Whereas previous incarnations communicated who deserved to wield power at home, however, Xi is more concerned with who wields power on the international stage.

Civilizational Values

The rhetorical flourishes of CCP-speak can form a fast and dazzling tapestry, and yet they all share a common thread. Whether it’s Deng’s Spiritual Civilization, Jiang’s Political Civilization, or Xi’s New Form of Human Civilization, the base logic behind these fanciful terms is the raw assertion of power and legitimacy.

China has made its rejection of universal values well-known. The well of resentment toward any criticism levied at Beijing, particularly for its human rights record, runs deep; and unlike its supposed rival, the US-led Summit for Democracy, the GCI is envisioned as a club in which members are expected to mind their own business.

“People need to keep an open mind in appreciating how different civilizations perceive values, and refrain from imposing their own values or models on others,” the State Council Information Office (SCIO) wrote in a piece celebrating the GCI. This alternative vision of value systems can be looked at in opposition to the universal values espoused by the CCP’s critics — a form of “civilizational values” that is informed by national conditions and not subject to criticism by anyone.

Xi Jinping’s “New Form of Human Civilization” is therefore one in which individuals’ rights are immaterial but nation-states’ rights are inviolable; wherein states’ treatment of their people is not open to scrutiny from within or without.

This latest contribution to China’s civilizatory discourse continues a pattern of discussion and reformulation that, as we have seen, goes back well over a century. But it is also, paradoxically, deaf to this process. Instead of building upon the established discourse, Xi — not unlike his predecessors — merely attaches its gravitas to a self-serving policy, giving grand, civilizational airs to what amounts a worldwide carte blanche for his administration.

All this brings us back to Samuel Johnson and his failure to grasp the difference between good, old-fashioned “culture” and this newfangled “civilization.” Why was the Global Civilization Initiative not called the Global Culture Initiative instead, and why did the SCIO not simply write about appreciating different cultural values?

Culture is understood as an expression of a community, bubbling from the bottom up. It is, by its nature, as changeable as any individual or community. Civilizations are superior to cultures, according to the logic that created this discourse, because they are capable of regimenting vast societies through the exercise of power. Cultural values are open to debate by all members of that culture, but civilizational values are whatever the civilizers — or, indeed, “Xivilizers” — tell us they are.