As a January 19 deadline looms to ban or sell TikTok, and as a key decision awaits from the US Supreme Court on the constitutionality of the related July 2024 act on “foreign adversary controlled applications,” many users of the popular video-sharing platform are already rendering judgment with their feet, seeking refuge in the most unlikely of places — the international version of a popular Chinese app that has a long track record of censorship and surveillance.

This week, more than 700,000 self-styled “TikTok refugees” have flocked to China’s RedNote platform, known at home as Xiaohongshu (小红书) — literally “little red book” — an Instagram-like platform that has long been a go-to space for posts on shopping, makeup, fashion and travel. The app currently has 300 million monthly active users, nearly 80 percent women.

The mass migration, announced with the hashtag #TikTokrefugees, has made the Chinese lifestyle-sharing app an odd escape route for American users of TikTok, some of whom have posted videos criticizing the actions of US lawmakers, and declaring provocatively that they are prepared to volunteer their personal data to the Chinese government. As of yesterday the hashtag had received more than 250 million views and was closing in on six million comments.

Some media, including CNN, have noted that the influx of users to China’s hugely popular RedNote, which to date has had few foreign users and little experience moderating content outside the Chinese language, has resulted in an unprecedented interaction of users across cultures and control regimes. TikTok, the American-based cousin of China’s domestic Douyin service, has never been an option for Chinese — resulting in alternative social universes spawned by the same algorithm. In its headline on the story, Semafor emphasized that the RedNote crossing was “an unlikely ‘cyberspace bridge’” between the two countries.

Hong Kong’s HK01, an online news outlet, quoted one Chinese translator from Hangzhou, Jacob Hui, sharing his reaction to his first interactions with American users of the platform. “I visited a livestream hosted by Chinese and American influencers on Xiaohongshu, and chatted with them, asking them things like what video games are popular in America.”

If the TikTok exodus surprised RedNote, it has delighted commentators in China, who have cast the event as an affirmation of China’s openness to cultural exchange, and further evidence of the hypocrisy of American values like freedom of speech — which state media have routinely panned over the decades as “so-called freedom of speech” (所谓的新闻自由).

Asked at a regular press conference yesterday whether China would step up controls on RedNote following the bump in foreign users, Guo Jiakun (郭嘉坤), a spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), lost no time in spinning the trend, saying coolly that social media use was “a matter of personal choice” and affirming China’s support for “strengthening cultural exchanges and promoting mutual understanding among peoples of all countries.”

On the question of risk, Hu Xijin (胡锡进), the often outspoken former editor-in-chief of China’s Global Times newspaper, tied to the Chinese Communist Party’s flagship Peoples’ Daily, called the American influx to RedNote “an opportunity rather than a risk.” Writing on the Shanghai-based Observer (观察网) platform, Hu added that this marked “a rebalancing of online power relations between the US and China.”

“If RedNote succeeds, China will have a new lever to promote common human values with the outside world,” said Hu.

China Central Television (CCTV), the country’s state-run broadcaster, declared that TikTok users had found a “new home.”

Short-Lived Positives

While US TikTok refugees from what some, including the American Civil Liberties Union, have criticized as unconstitutional overreach may have found a temporary harbor and scored a Pyrrhic victory, their enthusiasm could prove short-lived as they grapple with the real conditions on the opposite side of the bridge — the world’s most active and comprehensive system for real-time content moderation and political censorship.

There have already been indications from sources inside RedNote, as reported by Reuters, who have said the platform is already working on its internal content review capacity to deal with the influx of English-language influencers. These developments, demanded by cyberspace authorities for all services operating in the country, can be expected to roll out along with the extra services RedNote has feted — such as an English-to-Chinese translation function, now in the works, and an “English Corner” that connects language partners.

On Tuesday, as TikTok refugee flows were arriving on the shores of RedNote, the platform announced that it was implementing new measures to ensure content was “upward and virtuous” (向上向善) — not exactly an ethos associated with the TikTok homeland, which has thrived on threading together the inventive and unpredictable. This idea of the upward was also coded in the RedNote announcement for what the CCP terms “positive energy” (正能量), which refers to the need for uplifting messages as opposed to critical or negative ones — and particularly the need for content that puts the Party and government in a positive light. The platform talked about “increasing guidance and support for positive content” (加大对正向内容的引导与扶持).

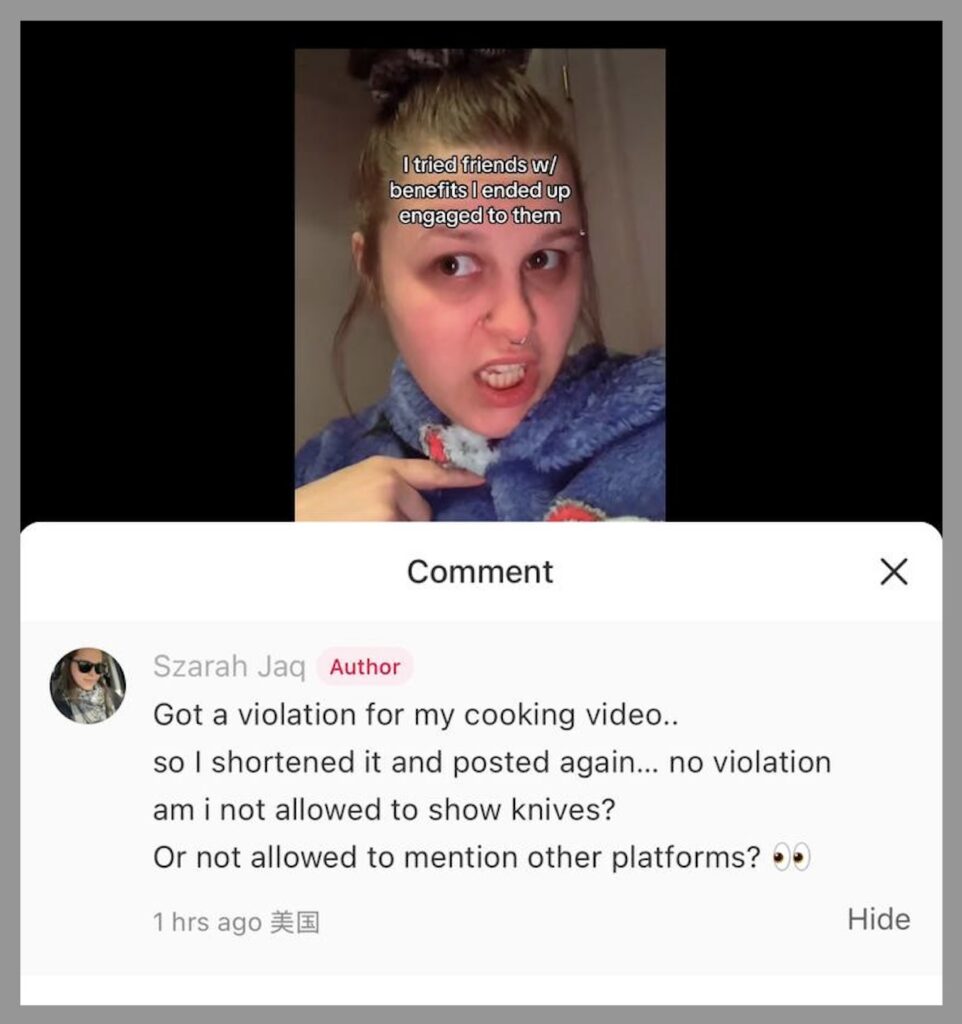

Just days into the exodus, there is already clear evidence that censorship mandates are being applied to RedNote’s new foreign users. One substantive result of this international cultural exchange, it seems, is that hundreds of thousands of American users of RedNote will soon have direct and intimate experience of what it means, and how it feels, to live under a system of all-embracing, granular, and unpredictable censorship. “Got a violation for my cooking video,” one American user posted, “so I shortened it and posted again, no violation.”

“Am I not allowed to show knives?”