Questions for Hubei’s Delegates

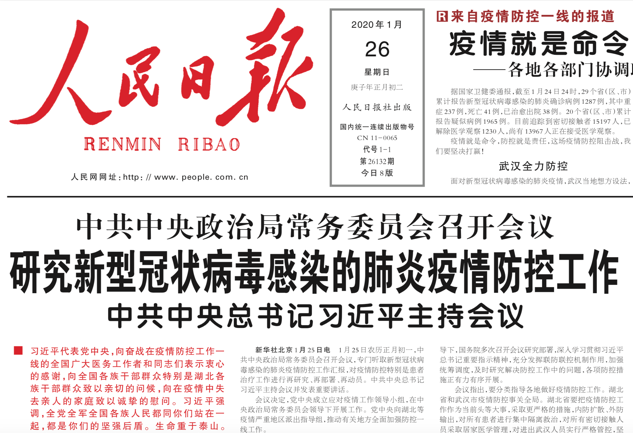

As the coronavirus continues to spread in China, so are questions multiplying and replicating in the online space. And while containing the virus is a matter of urgent concern, tackling these questions is of equal importance.

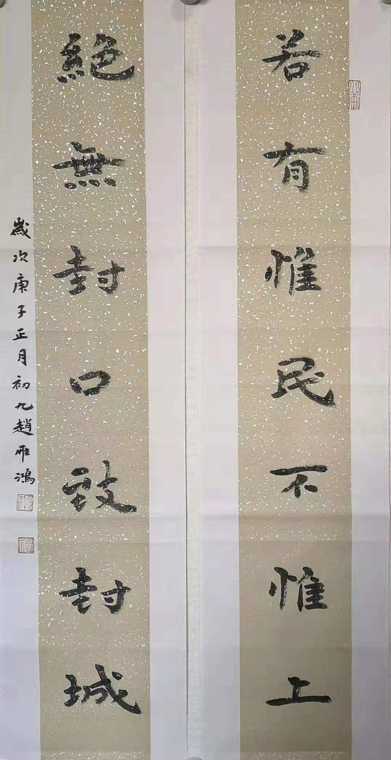

In recent days, a couplet has become popular online that goes something like this, though it is hard to do it justice in translation: “If popular will came first and not what leaders espoused, what need would there be to shut cities or mouths?”

The essential idea in this clever play on politics and history (which I won’t get into right now) is that we might not be in the place where we are now had it been possible in China to hear what people were trying to communicate in the weeks before the full scale of the coronavirus epidemic was exposed in the second half of January.

Many Chinese have noted with anger and dismay how officials in Hubei province and in Wuhan were focussed, even as the virus was wreaking havoc, on holding the so-called “two meetings” – annual gatherings of the people’s congresses and political consultative conferences at both the provincial and city levels. As those familiar with China’s political system will know, the people’s congresses and political consultative conferences are meant to be the channels by which the “popular will,” or minyi (民意) is expressed and conveyed.

How could it be, people have asked, that such a critical threat to the public was breaking out right in the midst of these “two meetings,” and yet the ostensible representatives in attendance completely turned their eyes away and kept their mouths shut?

When we search through media reports in Hubei province in January, the following picture emerges of the “two meetings” held at the provincial and city levels:

Times: the 4th Plenum of the 13th Wuhan CPPCC, held from the morning of January 6 to the morning of January 10, for a total of 4 days; the 5th Plenum of the 14th Wuhan People’s Congress, held from the morning of January 7 to the afternoon of January 10, for a duration of 3 days; the 3rd Plenum of the 12th Hubei Provincial CPPCC, held from the morning of January 11 to the afternoon of January 15, for a duration 4.5 days; the 3rd Plenum of 13th Hubei Provincial People’s Congress, held from the morning of January 12 to the morning of January 17th, a duration of 5 days.

Locations: The Wuhan municipal session of the “two meetings” was held at the Wuhan Theater (武汉剧院), located 5.8 kilometers from the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, where the virus is believed to have first spread to humans; the Hubei provincial session of the “two meetings” was held at the Hongshan Ceremonial Hall (洪山礼堂) in Wuchang, 17.3 kilometers from the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market. Readers may recall that on January 21, when the campaign from the top against the epidemic had already begun, the official Spring Festival Gala (春节团拜晚会) was held at this venue, attended by both the Hubei Party secretary and the governor – and some performers in the ceremony were reportedly ill at the time, according to official propaganda that reported this fact with an air of sacrifice and heroism.

Participants: 512 delegates were in attendance at the Wuhan CPPCC meeting. 657 delegates were in attendance at the Hubei provincial CPPCC, and 689 delegates at the Hubei People’s Congress. This brings the total in attendance at the “two meetings” at the city and provincial levels to 2,369 people.

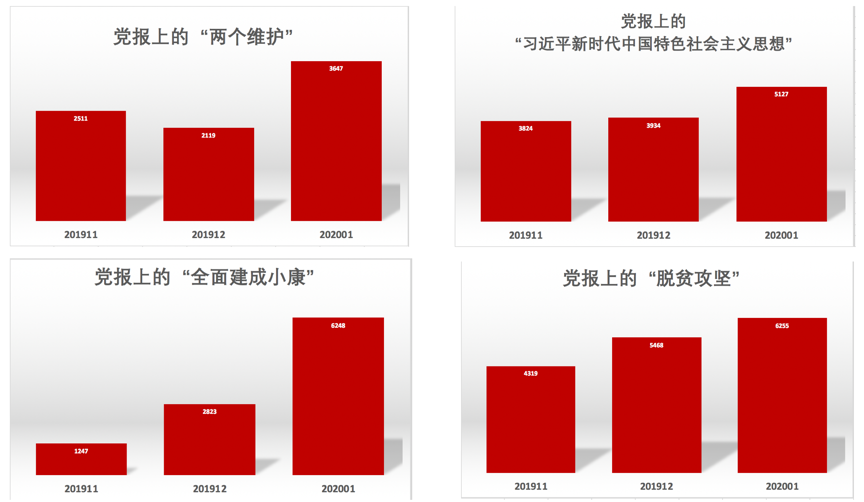

Propaganda: During the “two meetings” sessions at both city and provincial levels, a total of 148 pages were devoted to the meetings in four major newspapers, including Hubei Daily, the official organ of the Hubei Provincial Committee of the CCP, Chutian Metropolis Daily (a commercial spinoff of the Hubei Daily Newspaper Group), Changjiang Daily, the official organ of the Wuhan Municipal Committee of the CCP, and the Wuhan Evening Post (a commercial spinoff of the Changjiang Daily Newspaper Group). These 148 pages exclude frontpages reporting the opening and closing of the meetings, and pages simply publishing the texts of government work reports.

The vast majority of the content on these 148 pages consists of simple praise for accomplishments in 2019, and hopes for 2020. Here is an example of a special page in Hubei Daily reporting on the “two meetings.”

From the information above we obtain the following picture.

From January 6 to January 17, for 12 full days, Wuhan was in the midst of what the Party refers to as “two meetings time” (两会时间). Because all delegates to the CPPCC are present at the people’s congress, we can imagine 1,013 delegates crowded into the Wuhan Theater, and later 1,346 delegates crowded into the Hongshan Ceremonial Hall. Those present at the provincial event also included consuls from the United States, France and Great Britain, a number of citizen observers and a large number of journalists. The newspapers present readers with a picture of a momentous event.

As I prepare the analysis to follow, it is with a sense of unease. I can’t help wondering whether these 2,369 delegates are still doing OK, given what we now know of the spread of the virus at the time. The thought of them all gathered in close quarters as we see on the page above is a frightening picture in retrospect.

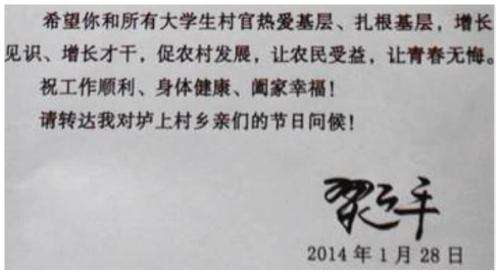

But considering that we now find in these same official Hubei media positive reports like this one praising many of these same delegates for working on the “front lines,” even “giving up Spring Festival,” in order to assist in fighting the coronavirus epidemic, there are some things that simply have to be said – and questions that must be asked. We can wish these delegates well and support their actions to control the epidemic, yet still expect answers as to why they remained collectively silent during “two meetings time,” under the immediate threat of the virus.

Let us review the facts about the context in which the “two meetings” sessions were held at the city and provincial levels in Hubei.

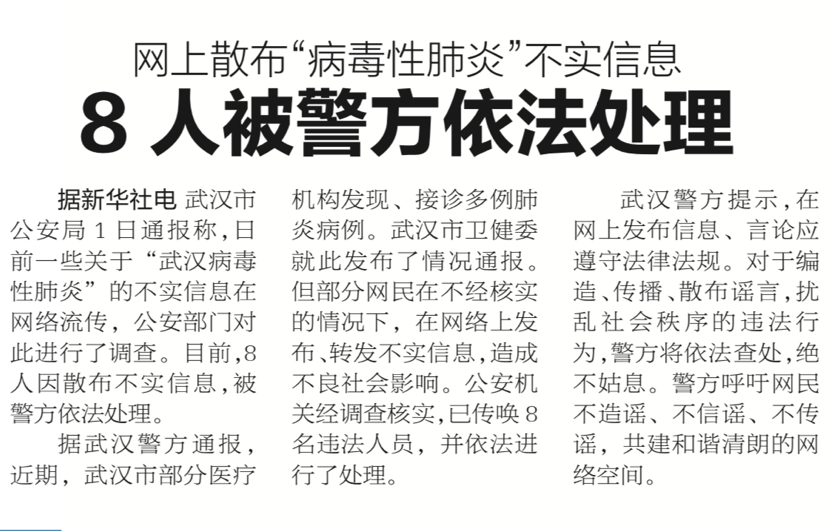

The opening of the “two meetings” in Wuhan was happening just as an outbreak of pneumonia was revealed. Here is the January 1 edition of Chutian Metropolis Daily.

And here is a page from January 6 edition of the Changjiang Daily reporting on the notice from the Wuhan Health Commission on “viral pneumonia” on the very same day as the opening of the Wuhan Municipal CPPCC.

Even though, as we now know, the situation was far worse than suggested by these notices from the Municipal Health Commission, the news of “viral pneumonia” was already out in Wuhan, and there were warnings from doctors already being shared through WeChat groups. It’s just not possible in this context that delegates were not cognizant of the outbreak.

Not only is it true that officials taking part in the meetings must have known about the situation – but in fact delegates from the healthcare field very possibly had first-hand knowledge of the outbreak and its seriousness.

Among Wuhan CPPCC delegates there were 16 from the healthcare field, including delegates from Wuhan No. 1 Hospital, Wuhan No. 6 Hospital, from the Union Hospital of Wuhan Medical School, from Wuhan TCM Hospital, and even from the Respiratory Clinic of Wuhan No. 1 Hospital. Among these, the Union Hospital was one of the earliest to treat coronavirus patients.

According to a report from Caixin, as early as December 31, “The five-story building housing the Infectious Diseases Ward of the Union Hospital had to convert on floor into an isolation ward for infectious respiratory disease.”

Among the Wuhan CPPCC delegates there was also a representative from the Wuhan City Epidemic Prevention and Control Center, and two from the Wuhan Health Commission.

The focus of the “two meetings” in Wuhan was on the notion of its being a “new first-tier city,” meaning that Wuhan would seek a seek first-tier status like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen by attracting further investment, promoting technology development, making moves in education and human resources and so on. These were the top policy issues.

Meanwhile, the coronavirus outbreak, this major challenge concerning the entire population of Wuhan, was nowhere on the agenda.

According to reports in Chutian Metropolis Daily, the major points of action for the general welfare during the “two meetings” in Wuhan were “transportation,” “housing,” “social security,” “education,” “ecology” and “healthcare.” The last of these, healthcare, was about “raising the health of the entire population.” Wuhan Mayor Zhou Xianwang (周先旺) demanded in his government work report that “the system of epidemic disease control be strengthened, raising capacity in dealing with sudden-breaking public health incidents and in treatment.”

But in news reports we cannot find any discussion of these points in relation to the coronavirus epidemic.

If we say that during its own “two meetings time” Wuhan missed the most optimal window in the control of the epidemic, then we can say that it was during the provincial “two meetings time” that Hubei missed its last opportunity to control the full outbreak of the disease.

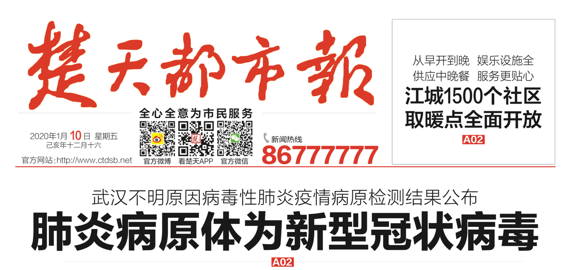

On January 10, the Changjiang Daily and other papers published the results of the investigation into the source of the cases of viral pneumonia, and the phrase “new coronavirus” entered the public view.

The participants in the Hubei provincial “two meetings” would certainly have seen such reports, and they would have heard the chatter in the streets before they crowded into the Hongshan Memorial Hall on January 11. We can be sure that these provincial delegates were by this time more knowledgeable about the situation than delegates during the city-level meetings had been – and this is especially true of the delegates from the medical field. By January 11, the day the Hubei Provincial CPPCC opened, at least 7 doctors had already been infected by the virus.

Among the delegates to the Hubei CPPCC, there were 26 from the medical profession. They were from Tongji Hospital, Union Hospital, the People’s Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan Central Hospital, Hubei TCM Hospital and others. Like Union Hospital, experts from the People’s Hospital of Wuhan University had already been dealing with coronavirus patients since December.

It was on December 30, in fact, that Li Wenliang (李文亮), an ophthalmologist (眼科医生) at Wuhan Central Hospital, posted the warning to his WeChat group for which he was admonished by police.

On January 11, the day the curtain opened on the provincial CPPCC, Li reportedly developed a fever. On January 12, the day the provincial people’s congress opened, he was admitted to the hospital. On February 1, his diagnosis was confirmed. On February 7, he passed away.

Among the delegates to the provincial CPPCC, there was one who served as Party secretary at the Hubei Health Commission. On the day the “two meetings” began, as media reported the understated Wuhan Health Commission notice, this official surely would have been in the know:

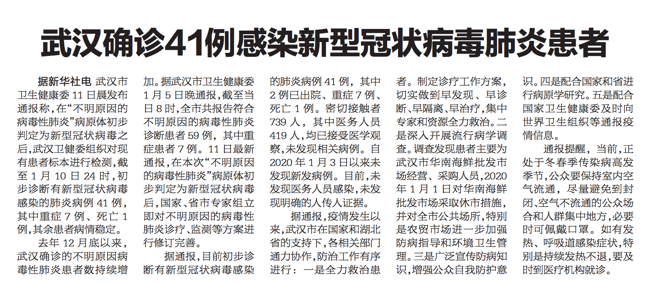

This news release from the official Xinhua News Agency says:

Since December last year, confirmed cases in Wuhan of cases of unexplained viral pneumonia have been on the rise. . . . According to notices, there have to now been 41 confirmed cases of new coronavirus infection presenting as pneumonia, with 2 cases already released, 7 in serious condition, and 1 death.

The report revealed that since the start of the outbreak, Wuhan had applied five countermeasures with the support of the national and provincial governments: 1) using all means to save patients; 2) conducting an epidemiological investigation; 3) widely publicizing information on disease prevention; 4) cooperating with the national and provincial authorities in investigating the origins of the disease; 5) cooperating with the national and provincial authorities to make timely information reports to the World Health Organization and others about the situation.

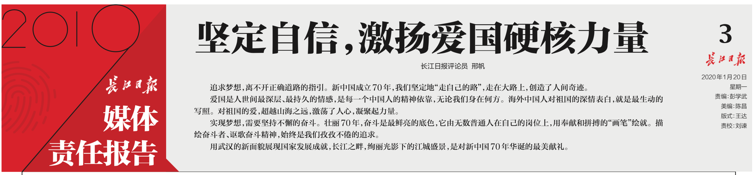

The shadow of the epidemic had already fallen, and the situation was serious. But there was already a full event calendar in preparation for Hubei’s “two meetings,” which would be used to celebrate the glorious achievements of 2019, and to promote the 2020 realization of a “comprehensively well-off society,” a key propaganda objective across the country.

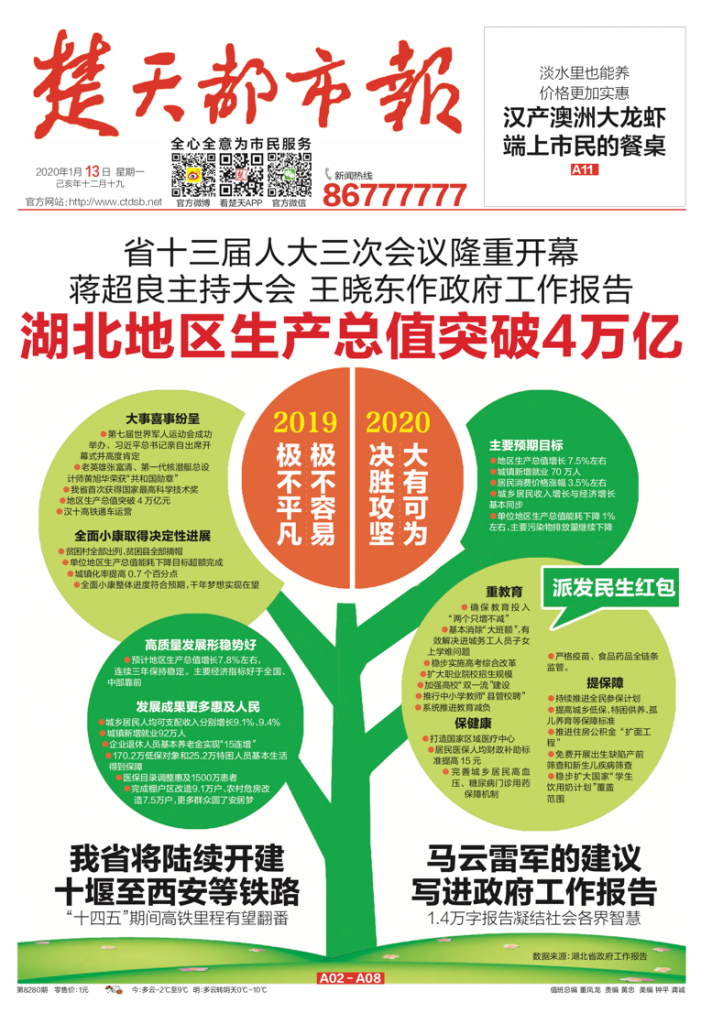

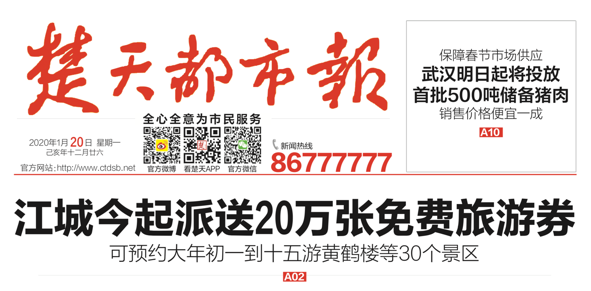

The front page of the January 13 edition of Chutian Metropolis Daily will give readers a clear sense of the mood of the “two meetings.” The page is all about the benefits for the people that were realized in 2019, and the riches to come for 2020:

The “two meetings” agenda promised three things to the people: “prioritizing education” (重教育), “raising protections” (提保障), and “preserving health” (保健康). That’s right, preserving health.

As an article in the Changjiang Daily, “Looking to Hubei’s 2020,” reported on January 13, the first task in protecting the welfare of the people in 2020 would be “creating a national and regional medical center.” On January 12, the provincial governor, Wang Xiaodong (王晓东), said in his government work report that “without the full health of the people, there can be no fully well-off society.” Wang demanded that, “the problems that cause the people anxiety must be treated as major issues, be met with real action, and be given full energy, steadily increasing the people’s sense of benefit, prosperity and security.”

What exactly caused the public anxiety at that moment? How could the 1,346 delegates taking part in Hubei’s “two meetings” not have known?

They raised their hands, they applauded, they actively discussed, they accepted interviews with reporters, but just as was the case at the Wuhan city level, there was not a hint at the provincial meeting about the coronavirus epidemic.

If we look at Wuhan in the early stages of the outbreak and at the “two meetings,” one clear question we are left with is why these 2,369 delegates all kept silent, so that these major meetings on policy were completely futile and unproductive in the face of a serious public health crisis. Some might respond with cynical laughter to such a question. They might ask: In China’s political system, what power do these 2,369 delegates actually have to address serious issues? Can we really treat these meetings as genuine opportunities for decision-making at all?

Well, OK. Point taken. But in any case, let’s review the operation of the system in terms of its original intent, stated mission and responsibilities.

1. The basic defined responsibility of delegates to the CPPCC and people’s congresses is to convey concerns to the upper levels. The outbreak had already begun in Wuhan by the end of 2019. So, of those delegates preparing to take part in the “two meetings” at either the city or provincial level, did anyone visit hospitals, the health commission or research clinics? Some delegates, who already had patients quarantined and under treatment in their own hospitals, didn’t need to go far to do so.

2. Toward year’s end, as the government work reports were being prepared at the city and provincial levels, it should have been typical practice to solicit views from different sectors. Did anyone raise the epidemic with the government? Did the government consider adding related content to the government report? In the end, why was nothing included?

3. On January 1, police in Wuhan issued a notice about 8 people being questioned and admonished for sharing “untrue” information about pneumonia cases online. On January 2, China Central Television also reported this news as well. How did delegates in Hubei and Wuhan, particularly those from the medical profession, respond to this? What impact did this incident have on the words or actions of these delegates as they took part in the “two meetings”?

4. Did any delegates at either the city or provincial levels exercise their legal right to inquiry, raise questions about the epidemic to health department officials, to emergency response department officials, or to the mayor or governor (for example, about medical personnel being infected by patients)?

5. Did any delegates at either the city or provincial levels exercise their legal right to deliberation (审议权), raising the issue of the epidemic during deliberation of the government work reports?

6. During the “two meetings” period, the Hubei Health Commission was already working with the National Health Commission to report information about the outbreak to the World Health Organization. If reports could be made to the WHO, why could the provincial government not also inform the 2,369 delegates to the “two meetings” at the city and provincial levels?

7. Did any delegates, including those from the medical profession, exercise their right to democratic supervision (民主监督) or political participation (参政议政), offering suggestions to the government on prevention and control of the epidemic?

8. Did any delegates submit views or proposals concerning possible measures to be taken to deal with the epidemic, for example through local laws or regulations, thereby exercising their right to make proposals (提案权)? Were earlier proposals made on the quarantine of Wuhan, for example?

9. The 2020 “two meetings” in Hubei were the first time that “delegate channels” were set up with the idea of allowing delegates to answer questions and speak up in public. Were these interactive channels actually used to respond to the most pressing concerns of the public? Why did the media not use these channels to address questions about the epidemic to delegates?

When the curtains closed on the provincial people’s congress in Hubei, Party secretary Jiang Chaoliang (蒋超良) praised “all delegates for faithfully fulfilling their responsibilities and reflecting the will of the people.” But the fact is that the “two sessions” meetings at both levels in Hubei in 2020, from conception to start to finish, suffered serious and unforgivable errors in terms of the exercise of responsibility.

The “two sessions” are not meant to be celebrations or carnivals. The people’s congress system and the political consultation system are meant, at least in principle, to be watchtowers and protective walls safeguarding society and the people. When such an immense threat faces the well-being of the people, it is impossible not to ask serious questions about what ails this system, about what kind of virus has infected it.

One month before the epidemic struck Wuhan, the 4th Plenum of the 19th Central Committee of the CCP released a policy document called “Decision Concerning Major Questions in the Continuation and Improvement of the System of Socialism With Chinese Characteristics, Promoting the Modernization of the Governing System and Governing Capacity” (关于坚持和完善中国特色社会主义制度 推进国家治理体系和治理能力现代化若干重大问题的决定). The Decision reiterated the point that “the people’s organs for exercising state power are the National People’s Congress and local people’s congresses at all levels.” It talked about “supporting and guaranteeing the people’s exercise of state power through the people’s congresses, and ensuring that the people’s congresses at all levels are democratically elected, are accountable to the people, and are supervised by the people, and that state organs at all levels are created by, are responsible for, and are supervised by the people’s congresses.”

The coronavirus epidemic has worked like a CT scan of China’s system, exposing the deep contrast between lofty rhetoric and real conduct, and displaying the “voiding out” (虚化) of the people’s congress and political consultative systems. Millions of people are now bearing the burden of a calamity brought out by this chronic disease of the system.