By Qian Gang — A post called “Conversations with an Old Comrade on the Eve of the 60th Anniversary of the PRC” (国庆60周年前夕一位老同志的谈话) has made the rounds on the Internet this week. The post, which comes ahead of the 60th anniversary of the founding of the PRC, and urges a critical reassessment of the Communist Party’s record, is now being systematically removed from blogs and bulletin boards inside China.

“Conversations with an Old Comrade” was purportedly compiled from recent interviews with a former high ranking CCP official. The online text refers to him as a “leader of the country and the party” (党和国家领导人), suggesting he held a position at the national level.

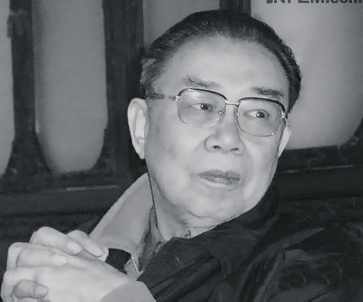

Although the authenticity of the post has not been confirmed, most who have read it believe it was indeed sourced from a senior party member. Readers have also remarked that the post is reminiscent of “50 Years of Trials and Hardships” (风雨苍黄50年), an influential piece penned by party elder Li Shenzhi (李慎之) on the occasion of the party’s 50th anniversary in 1999.

[ABOVE: Party elder Li Shenzhi, author of an important reflection on the CCP in 1999, passed away in 2003.]

Certainly, both Li Shenzhi and the mystery author of this week’s post share an interest in treating major PRC anniversaries as opportunities to talk about the shortcomings of CCP rule. If “Conversations with an Old Comrade” is authentic, however, it seems that the “old comrade” in question is even higher ranking than was Li Shenzhi.

The post begins in a very unconventional way. It relates how a young professor from the Central Party School paid a visit one day to the “old comrade” and addressed to him a series of questions raised by local and regional leaders. What things have gone unchanged in the 60 years since the establishment of the PRC? Why have these not changed? Is change possible?

The old comrade responds to the professor:

There are so many things that have not changed in the 60 years since the nation’s founding. The most basic, underlying fact is that this nation is still ruled by the Chinese Communist Party, and this is a truth everyone is clear about. But what other things stand behind this fact? For example, the CCP is a party of 70 million members. It is the world’s largest political party. And yet, the party has not yet been registered with the government authorities responsible for managing social organizations [namely, the Ministry of Civil Affairs]. And why is that? Our country still has no Political Party Law (政党法). After 60 years, this is something that has not changed. Our country still, to this day, does not have a political system in the modern sense. It is truer to say, in other words, that “the nation belongs to the CCP” than to say that “the CCP is the party of the nation.” After 60 years the concept of “party and government leaders” (党和国家领导人) has not changed. And in terms of national finances, no barriers whatsoever have been erected between the CCP treasury and the national treasury.

Look further and you see that China’s millions of soldiers are still called the People’s Liberation Army. In this area too nothing at all has changed. We still have no national armed forces in the true sense. The highest member of the armed forces is the highest leader in the CCP . . . After 60 years, nothing whatsoever has changed on this front.

Look within the CCP itself, and you see also that in 60 years no competitive system in the true sense has been established [to determine leadership positions]. It goes without saying that the same is true of the government.

The “old comrade” strongly opposes the slogan “60 years of resplendence,” which has been used to refer to the legacy of Communist Party rule in China. Is it possible to argue that the three or four years of the Great Leap Forward or the disastrous decade of the Cultural Revolution were resplendent? The CCP may not wish to subtract those painful years from the total, he suggests, but ordinary Chinese, historians and even ordinary CCP members most certainly will.

The old comrade recalls an exchange with an elderly party colleague who had presided over some work of the CCP’s Secretariat the early 1980s, and who resided in Shenzhen for several years in the twilight of his life. When the “old comrade” pays a visit to this elderly official, the latter shares one major delight and two major regrets about the path the country had taken.

His delight was that the economic reforms he had personally helped to promote in southern China had become a model for the whole nation to follow. One of his regrets was the party’s inability to rehabilitate its major historical errors. Another was the party’s failure to implement a policy of tolerance for alternative viewpoints. The “old comrade” recalls in the post: “He said very little. When he had finished speaking, the two of us just fell silent.”

The “old comrade” argues that tolerance for differing viewpoints should be a basic political ethic of the ruling party:

The Kuomingtang party lorded it over us for 22 years, closed down our newspapers and magazines, murdered members of our party, and expunged differing opinions from our schools. History has shown that these policies failed. The CCP, which has ruled for 60 years now, must not use similar methods against alternative viewpoints and against other people.

The “old comrade” in fact counts the CCP’s posture of intolerance toward popular viewpoints and ideas from scholars, experts and “members of democratic parties” as one of its most serious errors:

Sixty years is an occasion for both celebration and reflection. The whole nation must reflect back, and the whole party must reflect back. The ruling party, which is the nation’s only ruling party, and which has ruled for 60 years, should always have at least the most basic courage to reflect back. This, in fact, is a responsibility, a responsibility of the ruling party. Naturally, reflecting back would mean the airing of differing viewpoints. There is nothing at all unusual about this. If the climate becomes tense [ahead of the anniversary], if actions are taken to suppress [various ideas and activities], this suggests that the CCP is severely lacking in bearing and self-confidence. In my view, the views of the ordinary people, of members of democratic parties, of experts and scholars, and of the politically frustrated — these four categories of viewpoints — must be heeded and respected, and must not be suppressed. It discomforts me to realize that I am voicing ideas here that the ancients voiced more than a thousand years ago.

“Conversations with an Old Comrade” is identified online as having been “reorganized from four conversations with an old comrade of honor and integrity.” But if this is indeed the work of an elderly party member, who could it be?

There have been plenty of guesses. Most submit that this comrade must be a veteran of 1980s reforms in China, probably a member of the Secretariat of the 12th Central Committee of the CCP. Guesses have included Qiao Shi (乔石), Gu Mu (谷牧) and Wan Li (万里).

Others have suggested the work was done by a younger writer imitating the style of a party elder.

Whatever the case, I believe this article, which urges China and the CCP to mark the 60th anniversary of the PRC’s establishment by engaging in deep reflection rather than indulging in empty eulogies, does represent the views shared by leaders of conscience within the CCP.

[Posted by David Bandurski, August 7, 2009, 8:09pm HK]

SELECT DELETED POSTS of “Conversations with an Old Comrade”