By David Bandurski — Tensions between professional values and the party line have quietly marked every Chinese Journalist’s Day since the holiday was inaugurated on November 8, 2000. Nine years ago, the November 8 issue of Guangdong’s Southern Weekend argued boldly that journalists should show “social conscience” by exposing the truth. On the same day, however, propaganda leaders stressed that journalists must “be firm and unshakeable in carrying out the news theory and policy direction of the ruling party.”

This year, Journalist’s Day has come and gone with little cause for celebration among journalists in China who harbor professional ideals. The holiday was marked, in fact, by two distinct warning bells.

The first warning bell came as recent troubles at Caijing magazine culminated in the resignation of editor-in-chief Hu Shuli (胡舒立).

Hu’s departure marked the end of Caijing as one of China’s most outspoken and professional media outlets, and as a key destination and training ground for top journalists. It also underscored the way the professional spirit in Chinese media is now being squeezed more tightly than ever between the priorities of government censorship on the one hand and the prerogative of commercial profit on the other.

The second warning bell came in the form of a speech by politburo member Li Changchun (李长春) to mark Journalist’s Day, in which the ideological chief laid stronger emphasis on media control and avoided all pretense of caring about the public’s “right to know.”

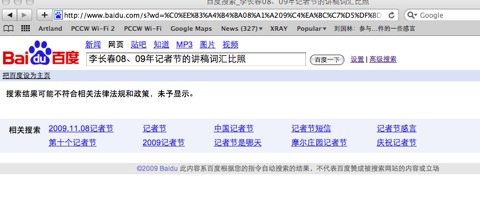

In a sobering analysis of this year’s speech, Song Zhibiao (宋志标), a journalist who works at Southern Metropolis Daily‘s editorial page, noted important changes from Li Changchun’s 2008 speech. Song’s post was quickly expunged from mainland-based websites.

[ABOVE: A search for Song Zhibiao’s analysis of Li Changchun’s Journalist’s Day speech through Baidu.com comes up with a warning saying results cannot be shown because they do not comply with laws and regulations.]

As in last year’s speech, Li gave top priority to “the principle of party spirit [in journalism]” (党性原则), the notion that news media must adhere to the party’s propaganda discipline and to “correct guidance of public opinion.”

But this reiteration of the priority of media control was complemented in this year’s speech by clear changes in official language concerning citizen’s rights and information.

Song notes that in Li Changchun’s 2008 speech the term “truth in the news” (新闻真实) made an appearance. This year, the term made a rapid exit.

Perhaps more worryingly, Hu Jintao’s so-called “four rights” — the right to know (知情权), right to participate (参与权), right to express (表达权) and right to monitor (监督权) — which appeared in the political report to the last Party Congress in 2007 and made Li’s speech last year, were dropped altogether this year from the main portion of Li’s speech dealing with priority work for the future. The language appears only in Li’s preamble, which outlines “valuable experiences” in media policy over the past 60 years.

These rather conspicuous absences seem to indicate that top leaders would rather not stake out a position on the ethic of neutrality (中立价值) for the news media, and intend to emphasize the news media’s fealty to the party over any interest, however tentative, in social rights.

Li Changchun’s speech on Sunday also placed a great deal of emphasis on the idea of “discourse power” (话语权) — the CCP’s “discourse power,” that is. This underscores in particular an interest in strengthening the party’s capacity to make its voice heard both domestically and internationally.

This is also an important reason why the term “public opinion channeling,” or yulun yindao (舆论引导), rises in the ranks of Li’s speech this year. This further drives home what we have been arguing here at CMP for months — that the party is reworking its media control system to allow traditional controls and active agenda-setting (“grabbing the megaphone“) to work hand-in-hand.

This change, which we have called Control 2.0, sees the priorities and tactics of propaganda as transcending national boundaries and requiring much more clever and aggressive techniques of persuasion. It can be glimpsed again in Li Changchun’s language this year about the need to “coordinate overall national interests on both the domestic and international fronts” (统筹国内国际两个大局).

In other words, China’s is taking its propaganda campaign global, and the success of domestic controls hinges on China’s success or failure on the international battlefield of public opinion.

More on that in tomorrow’s post, which deals with China’s unique vision of “soft power” as what one might call “attractive coercion” — in apt distortion, of course, of Joseph Nye’s formulation of “soft power” as “the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion and payment.”

Getting back to Li Changchun’s speech, though. Song Zhibiao sums up both the 2008 and 2009 speeches with the phrase, “Light on citizen’s rights, heavy on official power” (轻民权重官权).

But unlike last year, this year’s speech makes no effort whatsoever to conceal this fact. It is a bald pronouncement of the way things will be, and the way they should remain for some time to come.

“This is the news we receive on this Journalist’s Day,” Song concluded balefully. “We can avoid this holiday, but we cannot avoid attack from these principles that have been newly packaged and presented. This is the situation we in the press must face.”

[Posted by David Bandurski, November 10, 2009, 2:30pm HK]