In his July 1 speech to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, President Hu Jintao (胡锦涛) paused briefly from the self-congratulation to warn that the Party faces “four dangers,” including corruption and alienation from the people. We noted after the celebrations that Hu’s speech pointed to a tense environment within the Party, and suggested that the only real consensus right now seems to be the need for stability.

Of course, how to achieve that stability is a question that raises once again all of those essential but divisive issues Hu Jintao did not actively address in his speech — namely, rights defense, anti-corruption and political reform.

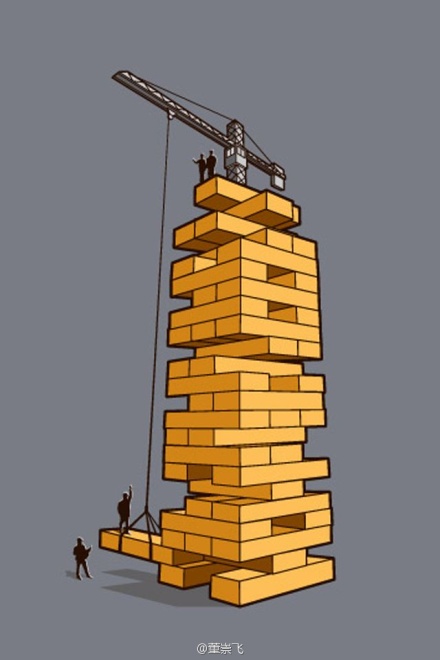

[ABOVE: “This is us [China] today!” wrote Dong Chongfei (董崇飞), a social media editor in Shandong province, on his Sina Weibo account on July 9. The cartoon depicts an unstable Jenga tower being built by a towering crane.]

In the most recent edition of the liberal Party journal Yanhuang Chunqiu (炎黄春秋), Zhou Ruijin (周瑞金), the former editor-in-chief of the official People’s Daily and an influential pro-reform Party elder, commemorated the CCP’s 90th anniversary with a stark warning: if tensions between the people and the government continue to rise due to unaddressed grievances and popular disgust at corruption and other injustices, the outcome could be catastrophic.

A full translation of Zhou’s essay follows.

Lately I’ve had a deep sense of anxiety as I’ve watched one occurrence after another of tensions between governments and people at the local level, which have become more an more acute. A number of officials at the local government level have abused their powers, again and again trampling the human rights, right to life and rights of property of ordinary people. Those affected turn to petitioning, make contact with the media, or go online to report their stories. If they turn to legal proceedings and other like methods in an attempt to protect the legitimate rights granted them in the constitution, they find that these channels for voicing their interests are blocked. What’s more, local governments will level such charges as “slander” (诽谤) or “extortion of the government” (敲诈政府) to go after them, “arresting them across provincial borders” (跨省抓捕) or simply locking them away in mental hospitals claiming that they are “psychological unsound.” Not long ago, Wuhan petitioner Xu Wu (徐武) was lucky enough to escape from a “mental hospital” after being locked up for four years, but then was openly dragged away by Wuhan police from the courtyard of Guangdong’s Southern Television (TVS) and again committed to a mental hospital. There was a buzz of public opinion around the country, but authorities in Hubei simply responded by suppressing media reporting.

These arrogant and unreasonable methods scraped the very bottom of the ethics of governance, seriously going against our Party’s political aim that says that “the Party works for the public, and exercises power for the people” (立党为公、执政为民). Lately the problem of petitioners “being [forcibly committed to] mental hospitals” (被精神病) has become, like the problem of forced property demolition (暴力拆迁), a painful new concern of the people. The first concern of many leaders now is to maintain the semblance of stability while they are in their posts. If nothing goes wrong they earn their political points (不出事, 出政绩).

In order to preserve the face and awe of the local government, and even of the various interest groups with which they have creeping connections, they will not stop at harming the interests of the people, and they even cloak themselves in the tiger skins of “stability preservation,” deceiving their superiors with claims [that they are battling] “hostile forces” and masses who “don’t understand the truth,” excusing their own incompetence in public administration and their ruthless offenses. They care not whether the price is loss of government credibility or the disintegration of popular support.

On the surface, these local [governments] can rely on public power and force to successfully suppress the discontentment and opposition of the people. For the moment, they can shield themselves from “static noise” in the media and on the Internet. But they cannot eliminate the hatred toward the government in the hearts of the people. When new hot topics [in the news and on the Internet] crop up, public anger will burst free, demanding payment with interest. The problem is, who will pay the debt of this anger pent up among the people? Local officials do not think about this issue. But they will cause our Party and our socialist system to have to answer for these combustible social tensions. In some areas, the “water level” of the people’s anger has already risen above the “plane,” and its only through a high-pressure campaign of stability preservation that the levee holds and temporary peace is ensured. But no one can say when the dam will be breached or collapse altogether. These methods spell disaster not just for the people, but spell disaster for the Party and the nation. As early as 2009, during the Deng Yujiao (邓玉娇) case that infuriated the public, web users warned: “Any instance of injustice must result in the further loss of the hearts of the people, and each popular resentment gathered up must ultimately breed great disaster.”

Ninety long years ago, our Chinese Communist Party rose among the peasants and the workers. Without weapons and without printing presses, but relying only on deep sympathies at the grassroots, its democratic politics and its longing for social fairness, it won the heartfelt support of the people. When Peng Pai (彭湃), the son of a major landlord in Haifeng County (海丰县), returned from his studies in Japan, his took off his long robe and wore a short trousers in its place and gave up his family’s rich lifestyle, in which “on average each [family] member had 50 slaves,” set fire to his own land deed and divided the land up among the poor, creating the Hailufeng Revolutionary Base (海陆丰革命根据地). The two sons of Chen Duxiu (陈独秀), [a co-founder of the Chinese Communist Party], when one was 17 and the other 14, went themselves to Shanghai for studies. They generally ate only flat bread and drank only water, not wearing cotton jackets in the winter, wearing rags in the summer. They were at one with the workers and ordinary city residents. They often helped the old and sick cart drivers pull their carts. And they became early heroes of the worker’s movement.

The attitude of the older generation of revolutionaries in receiving petitioners is something we should urgently think about. According to media reports, in March 1960, during the three years of the Great Famine that followed the “Great Leap Forward,” Red Army hero and Sichuan Daxian farmer He Mingyuan (何明渊) went to the capital [Beijing] to voice his grievances. Using the rather extreme method of lighting a lamp during the daytime in front of the Monument to the Martyrs on Tiananmen Square, he reminded the central government to pay attention to ordinary Chinese who were dying of hunger. In that time when “class struggle” was sweeping the land, the Party secretary of the Beijing Party Committee, Peng Zhen (彭真), did not toss him into prison, but actually prevented him from returning to his hometown, where he might have faced recrimination, and allowed him to go to [the city of] Wuhan in Hubei to live. When Chairman Liu Shaoqi (刘少奇) heard a report of this, he was so moved that he couldn’t speak for a time. The central leadership resolutely took measures in accordance with the actual situation in various regions, correcting the errors of the “Great Leap Forward.” While the old generation of CCP leaders did make this and that sort of error in administering state affairs, the care they showed when they faced the sufferings of the people remains moving.

Love of the people, closeness to the people and respect for the people are the precious assets that enabled our Party to earn the support of the people and be victorious over every trial. Against the glowing examples of the older generation of leaders, just how many thousands and tens of thousands of miles short are these local officials today who treat the people facing demolition and removal [of their property] as crickets and ants and petitioners as enemies?

Some people at the grassroots, because they’ve been driven into a corner, and have no remedies or recourse, will spare no pains [to make their grievances known] even if it means destroying their own bodies . . . [so we see] people facing demolition [of their properties] setting fire to themselves. Are members of our Chinese Communist Party not jarred by this. The rights and freedom of our citizens must be protected. The power vested by the people must be limited and checked by the system. Our Party leaders at all levels must expend the greatest energies possible to unblock the channels by which various social interests can be voiced and played out, and improve general administration, Party discipline, and judicial and public opinion mechanisms, all of this in order to carefully attend to the will of the people, dissolve popular anger, care for the sufferings of the people, and resolve the real interest issues of the people. Only by properly attending to the above, can we eliminate various factors of disharmony and truly preserve social and political stability.

Recently, the Ministry of Land and Resources send down an urgent notice demanding that local governments “desist from forcibly carrying out land appropriation and demolition and removal” in order to prevent the crude suppression of the people as a source of mass incidents of a grave nature. In contrast to Hubei province, when it came out in Hunan that lower-level family planning officials in Shaoyang City (邵阳市) were accused of selling children born in violation of the One-Child Policy, the Party secretary of Hunan, Zhou Qiang (周强), ordered a “thorough investigation”; a discipline inspection official set up shop in the township government office [in Shaoyang] and publicly listened to ordinary citizens as they told their stories, and he said to the victims: “Rest assured, we’ll handle this.”

I sincerely hope that in this era of transition in which social tensions are acute, our Party cadres at various levels are able to set straight their relationship with the people, staying vigilant day and night, truly acting in accord with Hu Jintao’s words, “Use power for the people, show concern for the people and seek benefit for the people,” truly acting in accord with Comrade Xi Jinping’s words, “Power is bestowed by the people,” acting in accord with Hu Jintao’s words, so all people can hear those warm and sincere words: “Rest assured, we’ll handle this.”