In the second disciplinary action this week against a major Chinese commercial newspaper, the publisher of Shanghai’s Oriental Morning Post has been dismissed, and one of its deputy editors has been suspended. This news follows the re-shuffling on Monday of New Express editor-in-chief Lu Fumin (陆扶民).

In the most general sense, the two actions — though not in any way related or coordinated — can be read as stemming from an all-round tightening of press controls in China ahead of the crucial 18th Party Congress later this year. That simple reading, however, tells us very little about the specific mechanisms that are at work in these cases.

So what is really going on? The bottom line, we don’t know. As the Hong Kong paper The Sun summed the cases up in an editorial this morning:

Inside the mainland propaganda system, there is a way to die that can be called “death by uncertain causes”. This is when the propaganda department settles a score once autumn has passed [as they saying goes]. If the bosses of a paper are not regularly and dutifully talking [the Party’s] politics, they will be pulled down mysteriously. The New Express and Oriental Morning Post are both examples of this.

Right now, the reasons being given for these “deaths by uncertain causes” are themselves mysterious to media insiders.

In the case of the New Express, the report tipped as the trouble-causer is this one about the pasts of a number of high-level Chinese leaders that ran in the July 9 edition of the official Jinan Daily. But the report, which the New Express ran in full the following day, is still readily available online, and the Jinan Daily version is still up too.

So what’s the problem here? The signs certainly suggest there was no overarching discipline violation. If central authorities see nothing to hide, why are local authorities being so fidgety over this?

In the case of the Oriental Morning Post, the problem report is apparently an interview with Chinese economist Sheng Hong (盛洪) run back on May 15, called “Private Enterprises Have the Right to Enter All Markets”. In the interview, Sheng argues that China must put an end to the preferential treatment of state-owned enterprises. But that’s hardly sensational stuff, and here in any case is the interview, surviving quite comfortably on the Oriental Morning Post website.

[ABOVE: The report supposed to have been the problem leading to disciplinary action at Shanghai’s Oriental Morning Post is alive and well on the paper’s website. What gives?]

Just to give readers a taste of the Oriental Morning Post interview in question, here are some of the more critical bits:

China has reached a point where public power must be checked, where public power cannot be allowed to be held ransom by vested interests, which cannot be allowed to wield monopoly power, the power to control massive amounts of limited resources.

One aspect is the [need to] protest small and medium-sized enterprises, allowing them produce and operate more efficiently. Another aspect is that if the resources state-owned enterprises control without cost are exchanged at cost under a market system, this will release greater efficiencies. Only in this way can the country move forward, and wealth be more plentiful.

The Goal of State-Owned Enterprises Should Be Public Benefit

The trend of reforms is to remove the monopoly rights of state-owned enterprises, the end the preferential treatment of state-owned enterprises — for example, it not acceptable that they hold national land for free and pay not rent. Aside from this, we must cancel the right of state-owned enterprises to obtain preferential loans.

. . . The State Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council should supervise state-owned enterprises on behalf of the people, but it has not taken on this responsibility. In fact, it has represented SOEs in bargaining with the people.

The government is the government of all companies in society, not just the government of the state-owned enterprises. Therefore, the trend of reform is to cancel the monopoly power of the state-owned enterprises, and cancel out preferential treatment of the state-owned enterprises. . .

Sheng makes his point directly enough, but these ideas are not especially provocative, and they hardly seem enough on their own to merit the dismissal of publisher Lu Yan (陆炎) and the suspension of deputy editor Sun Jian (孙鉴).

These are interesting cases in which the really sensitive issues are not in the reports that supposedly occasioned the propaganda actions, but rather in the actions themselves. In other words, while the supposed problem content is still readily available, the authorities are working actively to contain news and discussion of the disciplinary actions.

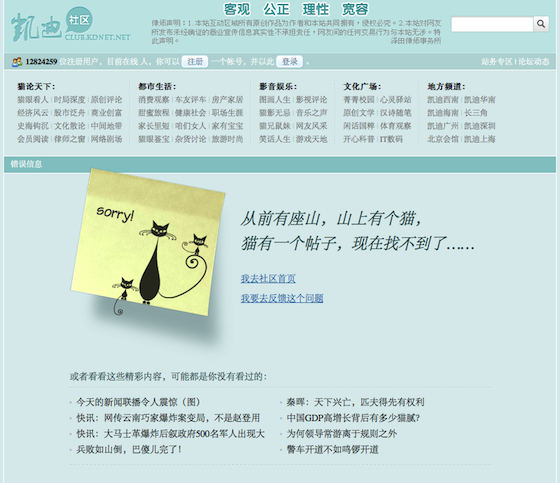

As Lawyer Zhang Huan noted on Weibo yesterday, much of the discussion of the disciplinary actions against the paper’s in online chat rooms was already being blocked. Search “Lu Yan” + “Oriental Morning Post” on Baidu, for example, and you got a thread at KDnet that was already dead, yielding up a “Page Cannot Be Found” warning.

And as plenty of examples in the JMSC’s “Deleted Posts” archive at the University of Hong Kong show, discussion of the cases on Sina Weibo was also being routinely thwarted.

Here for example, is a deleted post sharing an image of a report on the Oriental Morning Post story by Hong Kong’s Apple Daily.

Perhaps more information on these two mysterious disciplinary actions against leading commercial newspapers will be available in due course. For the time being, the issue to watch closely is how both papers continue to cover the news in the coming weeks and months.

Ever since the 2008 milk scandal, the Oriental Morning Post in particular has distinguished itself with its strong reporting. The paper did some of the best coverage of last year’s high-speed rail collision, which will mark its one-year anniversary on July 23. And it was one of the few newspapers in the country to speak out last fall on the continued detention of blind activist Chen Guangcheng.