In the most recent edition of Red Flag Journal (红旗文稿), a twice-monthly Party publication run by the journal Seeking Truth, the acting vice-minister of Shaanxi province’s propaganda department argues that Party-run media and new media now form two separate “public opinion fields” in China, and that this disconnect is an unacceptable challenge to Party rule.

Ren Xianliang (任贤良), who is also a vice-chairman of the All-China Journalists Association (中国记协) — charged with issuing press licenses and monitoring the conduct of journalists to ensure they “serve socialism and the overall interests of the Party and the nation” — has been one of the Party’s core theoreticians on propaganda and press control in recent years. Ren’s 2010 book The Guiding Art of the Public Opinion (舆论引导艺术:领导干部如何面对媒体) propounded many of Hu Jintao’s approaches to press control, essentially the idea that the leadership needed to find new ways to seize the agenda in the information age [See CMP analysis here].

[ABOVE: Ren Xianliang addresses journalists and editors during a government arranged tour of Shaanxi by Chinese internet media in 2011.]

Ren begins his piece in the Red Flag Journal: “In China today, two distinct fields of public opinion exist — one the traditional public opinion field comprising Party newspapers, Party journals, Party broadcasters and news agencies, the other the public opinion field of newly emerging media based on the internet.”

This state of affairs, says Ren, has “not only challenged the basic principle of the Party running the media (党管媒体), but has also resulted in confrontational division among social classes, damaged the credibility of the government and corrosively weakened the foundation of Party rule.”

Ren argues that the answer is for the Party to “have the courage to be hands on in its control” (真抓实管). He resolutely affirms the longstanding principle that “the Party runs the media” (党管媒体)”

Just like the [idea of] the Party controlling the military, of controlling guns and arms, the Party’s control of the media is an unassailable basic principle in terms of upholding the Party’s leadership, and under the current situation this [principle] can only be strengthened and must not weaken. Today, some web users use the internet to give vent to their anger, to generate and disseminate rumors, to mislead the people, and even to invade the privacy of others, and these are internet crimes. A number of so-called internet personalities (网络精英) manipulate sensitive incidents, maliciously attacking the current system, blaming and blackening the name of the Party and the government, in some cases even inciting the subversion of the Party’s leadership and its political rule. Some traditional media persons work in the home field by day and in their own private spaces at night, disguising their names with aliases to publish articles that couldn’t be published by their own media — they distribute these on the internet, and even sell them to other websites for profit.

Ren rues the fact that some users of Weibo and other platforms have drawn massive fan bases, so that “some Weibo VIPs have hundreds of thousands, millions or even tens of millions of followers . . . their influence substantially surpassing that of print media and even broadcast television.”

Ren’s note of alarmism over the Party’s loss of control and influence over media agendas is not entirely new. By the time of the SARS epidemic ten years ago, the notion that Party media were losing (or had lost) the agenda to a new generation of commercial newspapers and magazines like Southern Metropolis Daily, Caijing and The Beijing News in combination with commercial internet portal sites had already become a defining current of mainstream Party thinking on press and propaganda.

This sense of alarm in fact undergirded Hu Jintao’s 2008 press policy of “public opinion channeling”, or yulun yindao (舆论引导), the idea essentially that Party media needed to seize the agenda first and then expand the reach of their reports by using the commercial media, which were viewed as a “resource” for propaganda. Journalists in China have called this policy “grabbing the megaphone,” and these are the ideas that Ren Xianliang fleshes out in his 2010 book.

It’s not at all surprising, perhaps, to see that the sense of alarm has now shifted to social media.

Nor is it surprising that one of Ren’s solutions is a social media version of “grabbing the megaphone.” He writes: “We must promote the idea of Party members and cadres getting online, opening up Weibo accounts and speaking on behalf of the Party and the government, fostering our own group of ‘thought leaders’ on the internet and occupying the new media, this new public opinion front.”

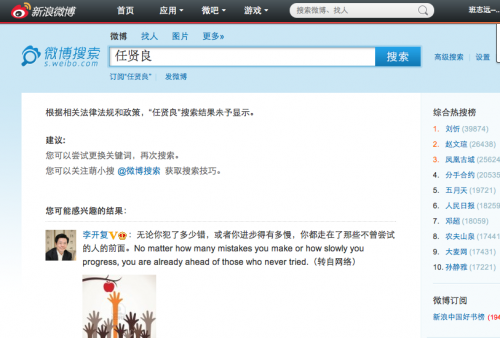

The prospects for influential pro-Party microbloggers seem poor at the moment, however. When I plugged Ren Xianliang’s name into Sina Weibo, supposing with admitted amusement that he hadn’t even opened an account, I found that matters were far worse.

Ren Xianliang, it seems, is himself is a sensitive keyword, yielding only the message that says it all: “According to relevant laws, regulations and policies, the search results for ‘Ren Xianliang’ cannot be shown.”