The dispute in China over the issue of constitutionalism has raged on for several months now. The word “constitutionalism” and the ideas with which it is associated have been subjected to an attack the intensity of which we have never seen.

In the past, I have categorized “constitutionalism” as a light-blue term. By that I mean that while is not generally welcomed within the official discourse of the Chinese Communist Party, neither is the term sensitive enough to make it taboo (or deep blue). The term has generally lingered in the “not promoted but not prohibited” (不倡不禁) category. You might see it used strategically by commercial media in China, but you would not expect to see it used by party media or by senior Party leaders. By contrast, deep-blue terms would include off-limits ideas like “multiparty system” (多党制) and “separation of powers” (三权分立), which are seen as fundamentally threatening to the leadership.

Right now, however, we have to ask whether the status of “constitutionalism” hasn’t changed. Has this light-blue term shifted into the deep blue? Has the concept of constitutionalism been thrown out entirely?

When we look at occurrences of the term “constitutionalism” in China’s media for the months of May-August 2013, distinguishing positive versus negative uses, we can see a clear upward trend in criticism of the concept.

Two Waves of Anti-Constitutionalism

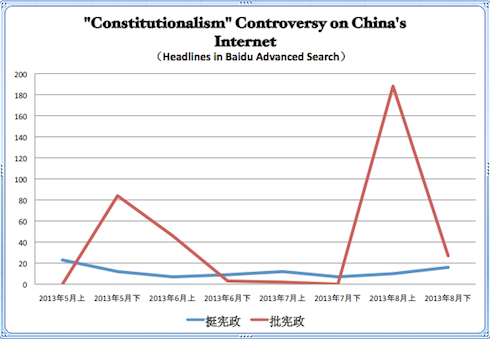

I obtained the following graph from an advanced search on Baidu, selecting for all articles in which the word “constitutionalism” appears in the headline. The search gives us a total tally of articles for each month, and we can then differentiate between positive and negative portrayals of the term. The blue line shows us occurrences of constitutionalism in a positive sense, and the red line shows us criticisms of the term and related ideas.

In the beginning of May, before the Party released a document outlining “Seven Don’t Speaks” — sensitive terminologies whose use was to be discouraged — positive uses of constitutionalism dominated, as we can see from the graph above. By by the second half of May, the campaign against constitutionalism is clearly reflected.

This kind of mass media campaign against constitutionalism is something we have rarely seen. Prior to this, the closest cases of criticism we saw were in lesser-known journals of theory. There was a piece by Chen Hongtai (陈红太) in the November 2004 issue of the journal Trends in Theoretical Research (理论研究动态) called “Views and Reasons Why the Term ‘Constitutionalism’ Cannot Be Used (关于不可采用“宪政”提法的意见和理由). And the November 2005 issue of Party History (党史文汇) ran an article from Xin Yan (辛岩) called “‘Constitutionalism’ Cannot Be Taken as a Basic Political Concept for Our Country” (不能把“宪政”作为我国的基本政治概念).

The first shot in this year’s campaign against constitutionalism was fired in the journal Red Flag. The piece, called “A Research Comparison of Constitutionalism and People’s Democracy” (宪政与人民民主制度之比较研究), was written by Yang Xiaoqing (杨晓青). The article was principally an attack on the idea raised by the Southern Weekly newspaper at the start of the year that the “Chinese dream” talked about by Xi Jinping should be a “dream of constitutionalism (中国梦,宪政梦). It also took aim against the idea of “socialist constitutionalism” (社会主义宪政), arguing that constitutionalism was a product of capitalism unsuited to a socialist system, and it growled against the idea of “the constitution and the law taking precedence” (宪法和法律至上).

On May 29, Party Construction journal ran a piece called “Recognizing the Basic Nature of ‘Constitutionalism'” (认清“宪政”的本质), written by Zheng Zhixue (郑志学), which said that “the main direction of ‘constitutionalism’ is clear, and it aims to abolish the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party.” In June, Red Flag ran a piece by Wang Tingyou (汪亭友) called “A Few Thoughts on the Issue of Constitutionalism” (对宪政问题的一些看法), which said the “Western nations hope to propagate the idea of constitutionalism in China as a means of abolishing the leadership of the CCP and the socialist system.”

The widespread re-posting of the above articles as well as a number of others resulted in the first peak you can see in the graph above.

The second peak occurred in August. On August 5-7, the overseas edition of the People’s Daily ran a series of pieces on the top its front page. They were: “‘Constitutionalism’ is Essentially a Weapon in a Public Opinion War” (“宪政”本质上是一种舆论战武器); “American Constitutionalism is No More Than a Name” (美国宪政的名不副实); “Doing Constitutionalism in China Can Only Be Like Catching Fish in a Tree, Subverting the Rule of Socialism” (在中国搞所谓宪政只能是缘木求鱼颠覆社会主义政权).

On August 19-20, the website of Seeking Truth journal re-posted two pieces from Haijiang Online (海疆在线), a leftist website that introduces itself as a “comprehensive service-oriented website” that “actively propagates the guidelines and policies of the Party and government, protects the interests of the nation and safeguards national security.” The first piece, by a certain Gao Xiang (高翔), was called “The Constitutionalism Wave is a Defiance of the Spirit of the 18th National Congress” (宪政潮是对十八大精神的挑衅). The second, by a certain Zheng Li (郑里), was called “The Theory of ‘Constitutionalism’ Misguides and Upsets Chinese Reforms” (“宪政”理论是对中国改革的干扰和误导). These essays were particularly ferocious in their criticism of constitutionalism.

Constitutionalism Fights With Its Back to the River

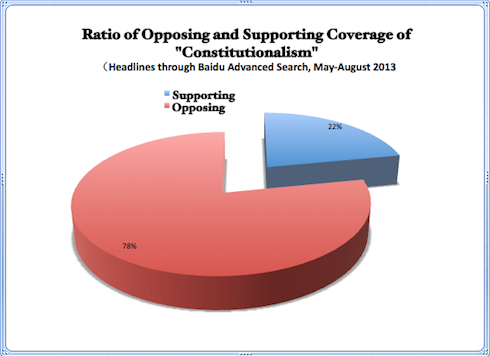

Looking at the overall share of the debate over constitutionalism from May through August 2013, we come up with the following chart. We can see that the share represented by the anti-constitutionalism camp dominates:

When we look at traditional media in China, it appears that “constitutionalism” has become a term of much greater sensitivity by the second half of May, regardless of whether the coverage is positive or negative. When we search the total universe of Chinese newspapers in the WiseNews database for the May-August period, we find just six articles in which “constitutionalism” appears in the headline and the concept is portrayed in a positive light. (Two of those articles appeared in the beginning of May.) Over the entire period, though, we also find just 11 articles in which “constitutionalism” appears in the headline and the concept is portrayed in a negative light.

This tells us that the internet is the principal field where the question of constitutionalism is being contested in China.

After the wave of anti-constitutionalism began, the first major piece in support of constitutionalism appeared on Caijing Online on May 24. The piece, “Constitutionalism is What Countries Under Rule of Law Should Be About” (宪政是法治国家应有之义), was actually an older piece by Xu Chongde (许崇德), a well-known scholar from the China Constitutional Research Center. In the piece Xu argues what the title suggests, that “constitutionalism is what a nation under socialist rule of law inherently means.”

On June 4, Singapore’s Lianhe Zaobao ran an interview online in which the site’s editor-in-chief, Zhou Zhaocheng (周兆呈), spoke to Chinese legal scholar He Weifang (贺卫方). It was called “Talking with He Weifang About China’s Constitutional Controversy” (对话贺卫方谈中国宪政争议). In this interview, which was shared widely across China’s internet, He Weifang emphasized that Xi Jinping had said soon after her took office that China must implement the Constitution. He Weifang also brought in Xi’s statement that “power must be shut in the cage of regulation,” an issue he said dealt directly with the issue of constitutionalism.

On June 10, an article written by Feng Chongyi (冯崇义) and Yang Hengjun (杨恒均), “Avoiding Constitutionalism Means Cutting Off the Road Forward for China” (拒绝宪政是断绝中国的前途), appeared on the internet in China. The article argued that constitutionalism was the institutional guarantee of rule of law, human rights and democracy all together. Constitutionalism, they said, had been the dream of the Chinese people for more than a century. And the anti-constitutionalism push, they said, was just a present-day form of obscurantism. They wrote: “In fact, China doesn’t face a question of whether or not to recognize constitutionalism, or whether or not to accept it, but rather it faces a point where, if it does not make institutional progress toward constitutionalism and democracy, it will suffer complete erosion and slide into a place beyond redemption.”

On June 21, another major pro-constitutionalism article hit China’s internet. This time it was from Cai Xia (蔡霞), a professor at the Central Party School. The article, a 30,000-word giant full of historical materials, looked back on the Chinese Communist Party’s explorations of constitutionalism and democracy, as well as its setbacks. It was a detailed study of how and why the Party had groped with such difficulty on the question of constitutionalism. But its conclusion was unambiguous: “If we continue refusing to push determinedly for political reforms, to push for the building of constitutionalism and democracy, the worsening of social tensions will be such that the ruling Party will lose the opportunity for reform altogether, and the government will have no space to manoeuver.

During this time, others stepping out with writings in support of constitutionalism included Jiang Ping (江平), Hua Bingxiao (华炳啸), Tong Zhiwei (童之伟), Guo Daohui (郭道晖), Wang Jianxun (王建勋), Wang Zhanyang (王占阳), Zhang Qianfan (张千帆), Rong Jian (荣剑) and many others.

The piece by Zhang Qianfan, a professor at Peking University, was posted on the influential China.com.cn on August 22, and some other websites that re-posted the piece added “constitutionalism” in the headline. The piece was called “Implementing the Constitution and Governing Longevity” (宪法实施与长期执政). “Opposing constitutionalism must mean opposing the Constitution,” Zhang wrote. He harshly criticized the opponents of constitutionalism, saying they hoped to turn the Constitution into an empty political slogan, a piece of paper that doesn’t matter once its been written. They advocated, he said, a form of “constitutional nihilism” (宪法虚无主义). The unspoken message of the anti-constitution camp seemed to be that in creating a Constitution, the Party had simply been toying with the people — that in fact China had no constitution, and state power was subject to no checks at all.

On August 29, Lianhe Zaobao posted a piece by Rong Jian (荣剑) called “Constitutionalism and the CCP’s Rebuilding of Legitimacy” (宪政与中共重建政治合法性). This article was again shared widely on the internet in China. Rong wrote: “Where is the new path by which the Chinese Communist Party can rebuild its legitimacy? When guns, pens and pocketbooks are no longer capable of controlling the nation’s people, if you want to win recognition and support from the people anew, is there any other path than constitutionalism?’

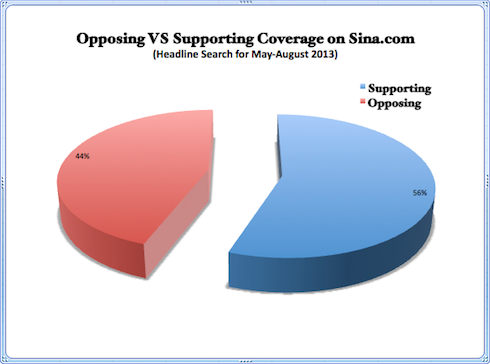

It has not been easy during this period for articles supporting constitutionalism to appear on China’s internet.

Articles like those mentioned above could not hope to be shared as forcefully as those attacking constitutionalism. The total number of articles attacking constitutionalism was not large, but they were shared widely across the internet. For example, Zheng Zhixue’s article was shared on 30 major websites, and Yang Xiaoqing’s was shared on 44 sites. Ma Zhongcheng’s piece, “American Constitutionalism is No More Than a Name,” was shared on 153 websites. From this we can see the abnormal level of force these articles had behind them.

To fight back, those in support of constitutionalism used every platform at their disposal, including Weibo. On August 10, I saw that a short film on Sina Video called “One-Hundred Years of Constitutionalism” (百年宪政), a history of China’s struggle for constitutionalism, was being promoted on Weibo. It had been shared more than 10,000 times and drawn more than 2,000 comments.

Of all articles on Sina.com from May through August with “constitutionalism” appearing in the headline, the majority are in support of constitutionalism, as we can see from the following graph.

Was Eliminating Constitutionalism Xi Jinping’s Idea?

I have personally experienced political changes in China since the Cultural Revolution and through the 1980s. My memories of the Party’s past ideological campaigns of criticism are still very fresh. Observing the controversy over constitutionalism since May, just looking at the anti-constitutionalism campaign itself, I have many doubts. It doesn’t look to me like a campaign of criticism that has been fully prepared and carefully organized.

I have said before that if the Party really wanted to ban words like “constitutionalism” it could do so. This time around, the word “constitutionalism” has nearly disappeared altogether in the traditional media. But then the net is opened just a bit, and discussion is allowed on the internet. Why?

In the middle of these two waves of anti-constitutionalism, a very strange valley appeared. During the second half of June and through all of July, it was as though someone had blown a whistle and called the game to a stop. Suddenly, the campaign against constitutionalism quieted. The banners were lowered, the drums muffled. Then, come August, the whole thing was whipped up again. So what happened in between?

In August, these articles from people under the pen names “Ma Zhongcheng” (马钟成), “Gao Xiang” (高翔) and “Zheng Li” (郑里) were not political scholars or legal scholars. Rather, they were from the Research Center for Naval Security and Cooperation (海洋安全与合作研究院) in Hainan, a mysterious center about which very little is known except that it is headed up by Dai Xu (戴旭), a senior colonel in the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF). Haijiang Online, their internet platform, gathers together a number of leftist and national security hawks.

What does it mean when a group of people with military backgrounds organizes a commando force to attack constitutionalism?

We need to pay attention to where exactly on the internet the attack against constitutionalism originated. Some people believe that it was the People’s Daily, the central mouthpiece of the CCP, and the Party journal Seeking Truth that first ran articles attacking constitutionalism. People’s Daily Online, which is run by the People’s Daily, posted two waves of anti-constitutionalism pieces (25 articles in May, and 52 articles in August). The situation at Seeking Truth Online was much the same, but its article were re-posts.

The platforms making original anti-constitutional posts — aside from Haijiang Online — were principally Red Flag (run by Seeking Truth), Party Construction (published by the Central Propaganda Department) and the overseas edition of the People’s Daily (of course under the People’s Daily banner). We must understand that Red Flag and Seeking Truth Online are not entirely the same things as Seeking Truth (the journal), and that the overseas edition of the People’s Daily is not entirely the same thing as the People’s Daily. [For more on the subtleties of the People’s Daily as a measure of Party consensus, see our analysis, “What’s Up at the People’s Daily?“]

The People’s Daily is the Chinese Communist Party’s most senior Party propaganda mouthpiece. The rise and fall of various political terms in the People’s Daily can clue us in to changes in China’s political environment. Over any case of political criticism emerging from the central Party, the People’s Daily must have something to say. It must, either through an official editorial or an opinion piece from the commentary desk, make a solemn pronouncement. What deserves very careful attention is the fact that, from May through August, the People’s Daily did not publish a single article speaking out against constitutionalism. Nor did Seeking Truth.

Now isn’t that mysterious?

Over this entire period, we find no articles in the People’s Daily with “constitutionalism” in the headline. If we search full text articles, we find just three including the term. Of these, two are international news reports, having nothing to do with the issue of constitutionalism in China. The third is an article published on page five of the June 18 edition of the People’s Daily. The headline of the article, written by Wang Yiwei (王义桅), is “The Civilizational Drivers of China’s Exceptional Growth” (中国超常增长的文明动力). One line in the article reads: “China has not implemented Western-style democracy and constitutionalism, and even is not a pure free market economy, and yet its economy has achieved exceptional growth over the past 30 years.” It’s hard to say whether or not this statement is meant as a criticism of constitutionalism.

Somewhat surprisingly, however, this article employs Xi Jinping’s statement about “neither can be mutually denied.” For those who don’t recall those remarks, Xi Jinping said during a January study session on the spirit of the 18th National Congress that “[we] cannot disavow Western capitalist democracy because of democracy under socialism with Chinese characteristics, nor can we disavow democracy under socialism with Chinese characteristics because of Western capitalist democracy.”

In summing up the controversy over constitutionalism over the past four months, there is one another important fact to note. The writers who have argued for constitutionalism have all used their real names. All are well-known scholars who have for years written about constitutionalism and political reform. Their articles reaffirm general understandings they have held for years. Most of the writers for the anti-constitutional camp, on the other hand, have not used their real names. The writing is ragged and poor, and full of brow-beating language reminiscent of that during the Cultural Revolution. Some of the writings are even crude, as though off the cuff. I find it very hard to believe that these could really be a concerted strike against a “reactionary current” by an elite team of CCP theory wonks.

There is little question, given the powerful push behind these articles, that they enjoyed powerful political backing. But exactly what sort of backing remains a serious question. Why, after all this time, haven’t the People’s Daily and Seeking Truth said anything? Is this strategic offensive? Or is it a kind of reconnaissance by fire, to see how the enemy reacts? Or is it, perhaps, a tactical probe?

Constitutionalism, whether we’re talking about a political term or an institutional arrangement, stands right now on a knife’s edge in China. Will it remain? Will it be thrown out? Will it live? Will it die? At the end of August, constitutionalism seemed to be in imminent danger. But as of yet, it has not become a deep-blue term. It is impossible to say whether Xi Jinping has even decided whether he means to “get rid of constitutionalism” (去宪政) or to “implement constitutionalism” (行宪政).

No doubt we will continue to see internal political rumbles reflected in the outward discourse. I will keep my eye on things, and let you know when there are more signs to read.