WHEN THE 19TH PARTY CONGRESS rolls around next fall, it will mark the ten-year anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party’s first inclusion of the term “soft power” in its crucial political report, perhaps the truest crystallisation we have of thinking at the highest levels of the country’s leadership. That official introduction of the term marked a new level of recognition that China needs more than just hard power to project its influence around the world. [A correction has been made to this story. See below.]

But setting aside for a moment the prickly issue of how China conceives of soft power as state-led public diplomacy as opposed to the more spontaneous effluence of culture, how is its soft power project going?

According to some experts, China is making real inroads in places like Africa, Latin America and Eastern Europe. Others, most notably Joseph S. Nye, the Harvard professor who coined the term soft power, say that while China’s substantial investments in soft power — possibly 10 billion dollars a year — have had some results, its “soft power ambitions still face major obstacles.” According to David Shambaugh, who has written extensively on the subject, “China’s favourability ratings are mixed at best, and predominantly negative, and declining over time.”

On the Soft Power 30 index for 2016, compiled by Portland Communications on the basis of objective metrics and international polling data, China ranked 28th in the world, just behind the Russian Federation and edging ahead of the Czech Republic and Argentina. The United States nabbed the top spot, pulling ahead of Great Britain.

For Chinese leaders, who still see soft power, and in particular what they call “cultural soft power,” as an outgrowth of Party and state power, one crucial aspect of the country’s “strategy” (a word revealing in itself) is “developing the vehicle or the mechanisms by which China can project this soft power.” Much of China’s official discourse obsesses over the idea that the West, and particularly the United States, monopolises “discourse power” internationally and that China must work to revamp the global information order (perhaps with Russia’s help).

The formal launch this month of China Global Television Network (CGTN), bringing the international channels of China Central Television (CCTV) and its digital presence under a new branding effort, should be understood as the latest push to develop an international broadcast infrastructure allowing China to advance its messages and flex its “discourse power.”

As bold and virile as this sounds, however, even a casual look at what CGTN currently has on offer indicates this is probably another misguided venture that will line the pockets of China’s state broadcaster while offering little in the way of globally compelling products.

Speaking to Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post, CCTV official Chen Lidong said the network’s domestic operations would not be affected by the change, “But the international-facing makeover will be extensive.”

How extensive? Well, let’s take a look.

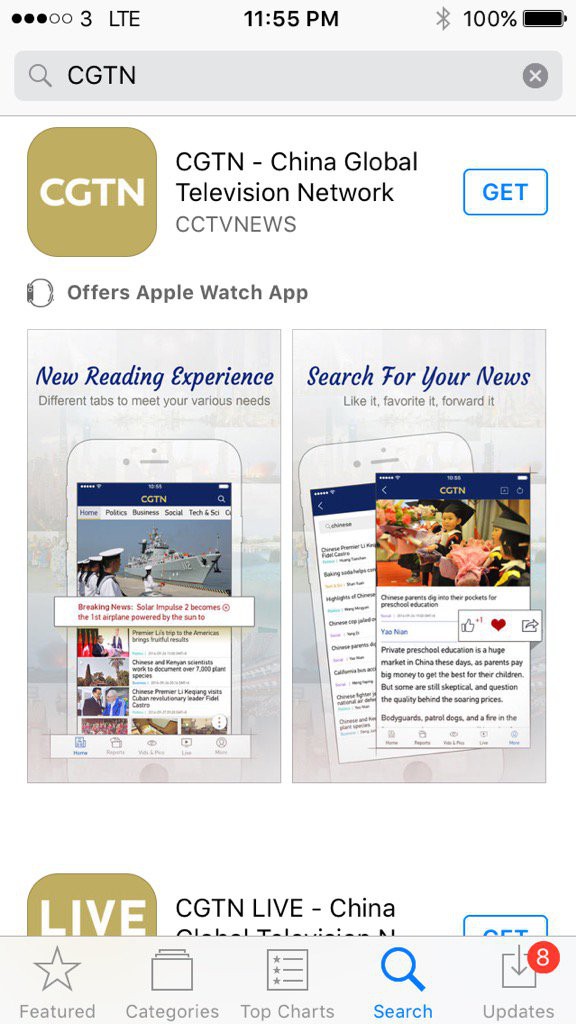

The brand-new CGTN has already released a pair of mobile apps for news and live broadcasts. Inexplicably, however, the albatross drapes still from the neck of this new brand, and “CCTVNEWS” is placed prominently just under “China Global Television Network” on both of the offerings in the App Store — next to a drab, pea-soup logo with the banal acronym.

After years of apparent soul-searching about the need to entice, and to understand foreigners and their interests, do we get a new approach to news reporting, writing and selection?

No.

The mock-up for the news app features a story about a Chinese naval vessel — hastening non-Chinese readers to thoughts of realpolitik. Two of the three stories coming on its heels are about Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visiting Latin America, betraying that all-too-familiar habit state media have of reporting the news as though interesting and significant things are done only by Party and government leaders.

Has CCTV really learned nothing about the human element? Isn’t that what the attraction at the core of soft power is ultimately all about? Could they not have featured a story instead about the Chinese soccer club offering Real Madrid 300 million Euros for Christiano Ronaldo?

Is it so difficult to stand in the shoes of one’s target reader?

CGTN’s pitch for its news app comes across as callow: “New Reading Experience — different tabs to meet your various needs.” Are we supposed to marvel at the ingenuity of tabs? (And how dyspeptic will I seem if I complain that the font advertising my “New Reading Experience” isn’t fresh or edgy, but a lacklustre cursive?)

Then again, perhaps my exasperation is heightened by the unfortunate fact that Apple has succumbed to Chinese pressure and pulled both the English and Chinese-language apps for the New York Times from the App Store. Hard power hard at work.

What about CGTN’s new website, to which all of CCTV’s international content has been directed?

With all due respect to CCTV’s Chen Lidong, anyone who turns to the first page of this extensive makeover will see the cracks and wrinkles.

When I first visited the new CGTN.com global website yesterday, the featured story suffered from strange breaks in both the headline (“Turkish authorities identify Istanbul nightclub attacker but”) and the teaser.

These evidently stemmed from basic kinks in the platform design — the kind of things one supposes should be ironed out before the president offers his felicitations on the front page of the official People’s Daily.

[NOTE: The italicised text below speculates that a byline on the CGTN site might be spurious owing to the fact that it is a politics report written by a reporter whose name, Dang Zheng, is a homonym for “Party and government.” In fact, there is indeed a reporter at CGTN named Dang Zheng. This is a delightful coincidence, but I apologise nevertheless to the reporter for the misunderstanding.]

Beyond the technical and design issues, there are basic journalistic concerns. The next politics story, my second experience with the platform, dealt with the former mayor of Tianjin, who has been expelled from the CCP for serious violations of political discipline. The report was written, we are informed, with “inputs from Xinhua News Agency.” But the writer, apparently, is a journalist named “Dang Zheng.”

“Dang Zheng” happens to be a homonym for “Party and government,” and while we can’t rule out the possibility, however remote, of a reporter on the politics beat who is actually named Dang Zheng, this is probably a liberty taken by the editors at CGTN.

Just as you could find at the old CCTV website, or at Xinhua’s English-language site, the occasional story to entertain or enlighten, there are odd stories at CGTN that surprise — like this little unpolished gem about a villager in Guangxi whose free outdoor film screenings have been curtailed by local officials.

But this does not look — not yet — like an extensive makeover. It looks like an ill-conceived web re-design alongside a simple acronym change. And as China, despite tightening controls, is in the midst of an exciting era at least in terms of technical and design innovation for the mobile internet, the CGTN platform seems to fall even flatter.

Why not find inspiration in the likes of The Paper or Jiemian?

In his recent well wishes to CGTN, Xi Jinping said that the platform should “fully seek closeness with its audience,” “using rich news and information, a clear Chinese perspective, and an expansive global way of looking at things in order to tell Chinese stories properly, transmitting China’s voice, allowing the world to see a colourful and three-dimensional China, and creating a favourable image of China as a builder of peace in the world, as a contributor to global development, and as a protector of the international order.”

Faced with such a medley of impossible expectations from those in power, is it any wonder that CCTV — I’m sorry, that CGTN — is confused?