On November 26, Chen Yufan (陈羽凡), a member of the celebrity rock duo Yu Quan (羽泉), was arrested in Beijing along with his girlfriend on charges of drug use and possession. According to a post made to the official WeChat account of police in the city’s western district of Shijingshan (石景山), Chen was arrested in “a local residence” after police received “a community tip” (群众举报).

The community members providing the tip off were apparently from a “community group,” or qunzhong zuzhi (群众组织) known as the “Old Neighbours of Shijingshan” (石景山老街坊).

In Beijing, this is one of a number of fairly well-known and well-documented community groups. Others include the likes of the “Chaoyang Masses” (朝阳群众), the “Haiding Internet Users” (海淀网友), the “Xicheng Aunties” (西城大妈) and the “Fengtai Advising Squad” (丰台劝导队).

These groups point to an emerging, and already quite developed, new model of community management in China that is being linked quite explicitly to a Mao-era experiment in social management known as the “Fengqiao experience,” or fengqiao jingyan (枫桥经验) — an experiment President Xi Jinping has voiced enthusiastic support for since he was the top leader of Zhejiang province 15 years ago, and which now seems to be a core idea for social and public security management in the Xi Era.

A “gridded community management system,” or wanggehua guanli tixi (网格化管理体系), has already been implemented in many areas across China, so that a now popular saying in the media and online goes: “In the north, there are the ‘Chaoyang Masses,’ and in the south the ‘Wulin Aunties'” (北有朝阳群众,南有武林大妈). The “Chaoyang Masses” refers, of course, to the aforementioned Beijing community group, while the “Wulin Aunties,” or “Wulin Volunteers,” refers to a group of around 500,000 mostly older women mobilised in September 2016 in Hangzhou to conduct community sweeps during a meeting of the G20. Images of the “Wulin Volunteers,” sporting their pink vests and caps, were widely reported in the media and on social platforms in 2016.

As Dushi Kuaibao (都市快报), a commercial newspaper in Hangzhou, remarked at the time: “Whether in Beijing or in Hangzhou, wherever the aunties roam there can be no secrets.” Whenever a new neighbour moves in, said the paper, the aunties know. If a pipe bursts somewhere, the aunties know.

This month marks the 55th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s so-called “Fengqiao experience,” referring to the idea of mobilising the masses at the grassroots of society to enforce proper conduct, political or otherwise. In the earlier Maoist context, this was about the use of the masses to turn “class enemies” onto the right path through direct person-to-person contact and “on-site monitoring and rehabilitation.” For more information on the idea and its history, readers can refer to CMP’s 2013 article on the subject.

This year marks the five-year anniversary of Xi Jinping’s national rehabilitation of the “Fengqiao experience” as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, and the 15th anniversary of Xi Jinping’s original rehabilitation of the “Fengqiao experience” as Party Secretary of Zhejiang province.

In light of these interlinked and overlapping anniversaries, we have seen a series of themed events across the country — and these can be seen in turn as connected in a roundabout but unmistakable way to Chen Yufan’s recent arrest in Beijing.

On November 7, the local CCP Committee in Beijing’s Xicheng District jointly hosted an event with the CCP Committee of Hangzhou’s Xicheng District (下城区) that was called — we are not making this up — the “North-South Aunties Dialogue and Exchange Event” (南北大妈对话互动交流活动). This shindig brought together members of community groups across the country to share their, well, tattle-tale experiences, all under the clear banner of the “Fengqiao experience.”

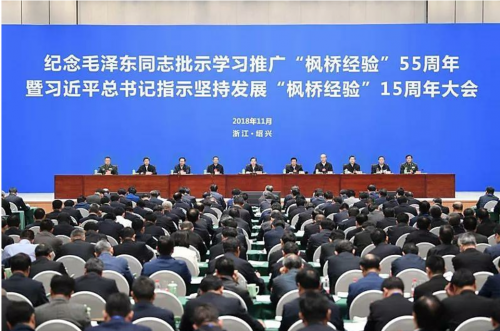

On November 12, the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission held a themed conference on the “Fengqiao experience” in Shaoxing, Zhejiang province, close to the origins of the concept and phrase in the Zhejiang city of Zhuji (诸暨). At the conference, the commission’s secretary, Guo Shengkun (郭声琨), praised the “Wulin Aunties” and the “Chaoyang Masses” for their “good work and good experiences.” Guo urged the need to create and apply a “‘Fengqiao experience’ for the New Era.”

This, in fact, has already been happening — and China’s countryside has been a major focus of activity. In September this year, the CCP released its Plan for Strategic Revitalisation of the Countryside 2018-2022 (乡村振兴战略规划: 2018-2022), which included explicit reference to Mao Zedong’s 1960’s concept: “[We must] comprehensively promote the ‘Fengqiao experience,'” said the document, “with small matters not leaving the village, and larger matters not leaving the township.” It added: “[We must] explore the tactic of gridded community management, promoting meticulousness and precision in grassroots services and management.”

All of this means that an army of aunties should be on the march in a village near you.

In 1963, when this experiment in social management was attempted in the Fengqiao District of the city of Zhuji, the idea was to “unleash and rely on the masses, adhering to [the idea of] not reporting tensions to superior levels, but rather resolving them locally.” This formed the core idea of what is called the “Fengqiao experience.” At the time, Mao Zedong issued written instructions ordering that the experiment be tried and applied in “various areas.”

On November 25, 2003, almost exactly 15 years ago, Xi Jinping, then Party Secretary of Zhejiang province, hosted a ceremony to commemorate the 40th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s written instructions on the “Fengqiao experience.” At that ceremony, Xi urged the renewal and innovation of the lessons of Fengqiao, saying that “taking the study and promotion of the ‘Fengqiao experience’ in the new era as the chief starting point in strengthening social and public security management.”

A headline on the front page of the official Zhejiang Daily on November 27, 2003 read: “Studying and Innovating the ‘Fengqiao Experience’ to Accurately Handle Internal Contraditions of the People in a New Era: Xi Jinping Delivers Speech, Lü Zushan Presides.” Lü Zushan was at the time the governor of Zhejiang, and therefore Xi Jinping’s number two, but we can suppose that the core ideas involved in that 2003 conference were reflective of Xi’s vision, crafted with those arrayed around him as he edged toward his designation as China’s heir apparent at the 17th National Congress in 2007.

The headline seems in retrospect to offer a tantalising glimpse of core leadership ideas to come. There is talk of “innovation” of a Maoist concept for a “new era” — though “new era” here is xinshiqi (新时期), rather than the much grander xin shidai (新时代) to come. And certainly this year, as China marks the 55th anniversary of the “Fengqiao experience,” the 15th anniversary of the 2003 conference on the concept is also being portrayed as an important political moment that should equally be marked.

A November 2018 conference held in Zhuji, Zhejiang province, celebrates both the 55th anniversary of the “Fengqiao experience” and the 15th anniversary of Xi Jinping’s rehabilitation of the concept.

Xi Jinping, who once rehabilitated the “Fengqiao experience” for a new era in Zhejiang, has now rehabilitated the “Fengqiao experience” for the New Era in China.

In this New Era, Xi Jinping’s vision of “strengthening social and public security management” through mobilisation of the masses can be seen in the activities of such “community organisations” as the “Old Neighbours of Shijingshan” (石景山老街坊), the group whose tattle-tale ways led last Monday to the arrest in Beijing of a Chinese rock ‘n’ roll celebrity, and the cancellation of his band’s 20th anniversary concert.

For Chen Yufan, as for millions of his fans, this rude awakening will be the first, and probably not the last, “Fengqiao experience.”

This article was written in collaboration with researcher Dorothy Dong.