Wandering through the online world of the WeChat platform over the New Year holiday, I came across an interesting pair of images shared by another user. Both were of books by Shen Haixiong (慎海雄), a deputy minister of China’s Central Propaganda Department, the Chinese Communist Party’s internal body responsible for information and ideology, and the current head of the China Media Group, the consolidated state broadcasting group formed almost a year ago — and also known as “Voice of China.”

Both books dealt with the study of the ideas and utterances of President Xi Jinping, playing on the surname “Xi” (习), which can also mean “practice” or “study.” And both were the same drab shades of yellow and manila. The first book was called Views on Putting Xi Study Into Practice (学习实践论), while the second was called Studying Xi in the Present (学习进行时).

But the similarity between the two books that really caught my eye was the way that both used a very distinctive version of the character for “Xi,” one I suspected might be the calligraphy of Xi Jinping himself.

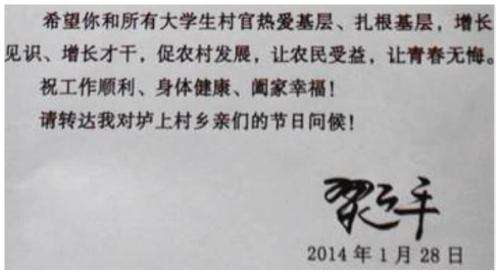

A quick internet search and I was able to dig up the following letter written by Xi Jinping in January 2014 to so-called “college student village officials” (大学生村官), referring to recent college graduates who work as assistants to senior village officials.

Notice the signature on the letter to “college student village officials,” in which Xi Jinping wishes them all generally good health and good fortune, noting their contributions as the “grassroots.” This certainly looks like the same “Xi” with a flourish that we see on the cover of both of Shen Haixiong’s books.

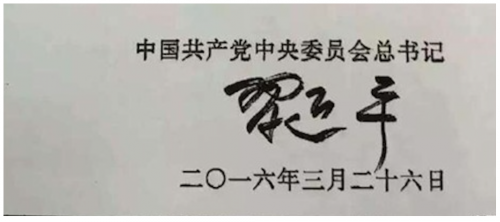

And then there is this letter, which Xi Jinping wrote in March 2016 to Hung Hsiu-chu (洪秀柱), then the chairwoman of Taiwan’s Kuomintang party. The letter is signed March 26, 2016, by “General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi Jinping.”

At this point, we can safely confirm that this is indeed Xi Jinping’s own hand, and by extension that the “Xi” used by Shen Haixiong on his book covers is Xi Jinping’s handwriting too.

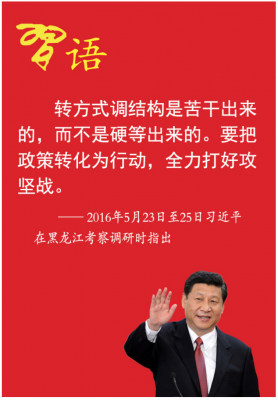

We can find the same “Xi” elsewhere on the internet without much difficulty. This time it is in a reference to the “Words of Xi,” presented as a regular feature in state-run media.

The yellow character for “Xi” in the title is unmistakably Xi’s own handwriting.

Appropriating the handwriting of top leaders for one’s own purposes is not really something serious, but it does have quite significant echoes in the history of the Chinese Communist Party. I’m referring, of course, to the formalisation and widespread application — a process that in Chinese we call jizi (集字) — of the calligraphy style of Mao Zedong.

Mao Zedong was known as a calligrapher, and he wrote out the mastheads of many Chinese newspapers. There were also certain cases, however, where newspapers were unable to invite Mao to personally write out their mastheads and chose instead to do cut and paste jobs using existing examples of his writing, cobbling together their own Mao mastheads.

In recent years we’ve seen a proliferation of this phenomenon of jizi in the Chinese media. And stumbling across Shen Haixiong’s books on WeChat sent me on a brief chase through recent examples, which can be very illuminating.

Readers may remember that in March last year a state-produced documentary lauding China’s economic and technological achievements under Xi Jinping was released to great fanfare. The documentary, which became the highest grossing documentary film in China’s history upon release, was called “Amazing China,” or in Chinese lihaile wo de guo (厉害了, 我的国). Here is one of the promotional images for the film.

Some of you, taking a closer look at the calligraphy used for the promotional image, may note that it seems vaguely familiar. And in fact, we can find identical calligraphy being used in recent months in newspapers across the country for “Amazing China” features, and for column headings and the like.

For someone who lived, as I did, through the Mao era, a question keeps sneaking up: Isn’t this calligraphy in Mao Zedong’s hand?

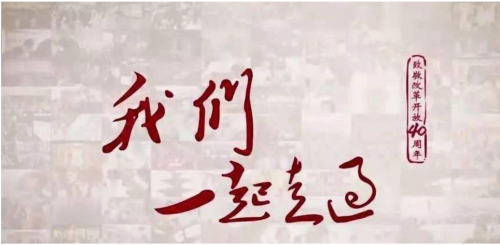

Once you start looking for it, you quickly find that Mao-style calligraphy is being used all over the place these days. Here, for example, is a promotional add for another recent documentary from China Central Television commemorating the 40th anniversary of reform and opening. The documentary is called “We Experienced it Together” (我们一起走过):

Mao’s hand here is unmistakable. And what a contrast that makes when you stop to think about it. At its very heart, reform and opening was a moment of “transformation away from Mao” (改毛), a repudiation of the suffering and damage his actions inflicted upon the country. To use the Chinese Communist Party’s own discourse for this pivot away from Mao, it was about “correcting mistakes” (纠正错误). So here we have Mao’s pretty calligraphy introducing a documentary about 40 years of reform and opening. Is that really appropriate?

Besides, considering this as an instance of jizi (集字), we might ask when Mao ever uttered the phrase, “We experienced it together.”

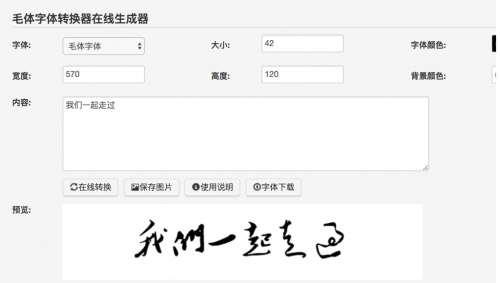

But adapting Mao’s script to present-day phrases and sentiments may be a whole lot easier than you think. I found a website, in fact, that is dedicated to Mao’s unique calligraphy style, and it includes a “Mao Script Generator” (毛体字体转换器在线生成器) allowing anyone to transform simple characters into Mao’s own hand.

If we give “Amazing China” a try, here is the result we come up with:

This is without a doubt the script used for the documentary film’s title, only the character for li (厉), or “fierce,” has been changed somewhat — probably a decision by the producers of the film made out of concern it might otherwise be unrecognisable to most Chinese.

I couldn’t resist putting “We experienced it together” into the Mao Script Generator next:

That certainly works. Who could have guessed just how easy it is to add Mao Zedong’s handwriting to a documentary about 40 years of reform and opening, a policy initiated more than two years after his death?

But the Mao Script Generator doesn’t always work to great effect, as demonstrated by the following propaganda image for the 500th anniversary of socialism, apparently thrown together by the Beijing Institute of Technology.

In Mao Zedong’s poem “The People’s Liberation Army Captures Nanjing” (七律.人民解放军占领南京), there is a line about how “change is the law of nature” (人间正道是沧桑), which provides the four characters in the phrase above. There is calligraphy from Mao’s own hand for these four characters. But for some reason unknown, the Mao Script Generator uses Mao’s version of the last two characters but throws out different versions of the first two characters, zheng (正) and dao (道).

So it seems this online Mao Script Generator brings together a vast collection of Mao writing, and can put these together into various different phrases as suits the expectations of the user.

With such power at my fingertips, I could hardly resist entering my own choice, a phrase that has nothing whatsoever to do with Mao Zedong, a phrase we can perhaps expect to be on the rise in the coming months: “Xi Jinping Thought” (习近平思想):

I wonder if you notice anything of interest. Let’s try it with just the character for “Xi”:

In fact, the “Xi” that emerges from the Mao Script Generator is almost identical to that used by Shen Haixiong on the covers of both of his books.

And so a little secret emerges. President Xi Jinping has fashioned his signature in the Mao Zedong calligraphy style.