An op-ed in the Apple Daily by LEGCO member Kwok Ka-ki argues that China’s yearning for ‘Mr. Democracy’ will only grow stronger.

Here in Hong Kong still, such questions can be discussed more openly, of course. And so Kwok Ka-ki (郭家麒), a Legislative Council member from the Civic Party, wrote this week in the Apple Daily that today, 100 years after the May Fourth Movement, “China blindly develops its economy, and science and technology, mistakenly believing that this translates into national strength.”

Kwok suggested that China was only strong on the outside while brittle on the inside. “In a country without freedom and without democracy, there is no space for the people to make their will and demands heard,” he wrote. “Once people have satisfied their basic hunger for life, they will naturally grow envious of the freedom, democracy and culture of Western countries. The voices in China calling for democratic progress will only grow louder and louder. . . . I believe that someday the totalitarian [government] will fall, and Mr. Democracy will be found on Chinese soil.”

In response today, the Ta Kung Pao, a newspaper controlled by the Central Government’s Liaison Office, went on the attack, dismissing the “distorted reports” of the Apple Daily, which it said had wrongly suggested that President Xi Jinping had twisted the meaning of the May Fourth Movement by placing his emphasis on nationalism.

“This is a distortion of history, and a major insult to the spirit of the May Fourth Movement,” said the newspaper. “As we know, one of the slogans of the May Fourth Movement that year was a call for ‘Mr. Democracy’ and ‘Mr. Science,’ meaning for democracy and science. But why did the youth call for and demand ‘Mr. Democracy’ and ‘Mr. Science’? What was their goal? Was it not so that the nation could prosper and grow strong, for love of their country?”

The Ta Kung Pao returned the issue to the core logic of the Chinese Communist Party — that the youth must love their country, and this means love for the Party and its leader:

Here in Hong Kong still, such questions can be discussed more openly, of course. And so Kwok Ka-ki (郭家麒), a Legislative Council member from the Civic Party, wrote this week in the Apple Daily that today, 100 years after the May Fourth Movement, “China blindly develops its economy, and science and technology, mistakenly believing that this translates into national strength.”

Kwok suggested that China was only strong on the outside while brittle on the inside. “In a country without freedom and without democracy, there is no space for the people to make their will and demands heard,” he wrote. “Once people have satisfied their basic hunger for life, they will naturally grow envious of the freedom, democracy and culture of Western countries. The voices in China calling for democratic progress will only grow louder and louder. . . . I believe that someday the totalitarian [government] will fall, and Mr. Democracy will be found on Chinese soil.”

In response today, the Ta Kung Pao, a newspaper controlled by the Central Government’s Liaison Office, went on the attack, dismissing the “distorted reports” of the Apple Daily, which it said had wrongly suggested that President Xi Jinping had twisted the meaning of the May Fourth Movement by placing his emphasis on nationalism.

“This is a distortion of history, and a major insult to the spirit of the May Fourth Movement,” said the newspaper. “As we know, one of the slogans of the May Fourth Movement that year was a call for ‘Mr. Democracy’ and ‘Mr. Science,’ meaning for democracy and science. But why did the youth call for and demand ‘Mr. Democracy’ and ‘Mr. Science’? What was their goal? Was it not so that the nation could prosper and grow strong, for love of their country?”

The Ta Kung Pao returned the issue to the core logic of the Chinese Communist Party — that the youth must love their country, and this means love for the Party and its leader:

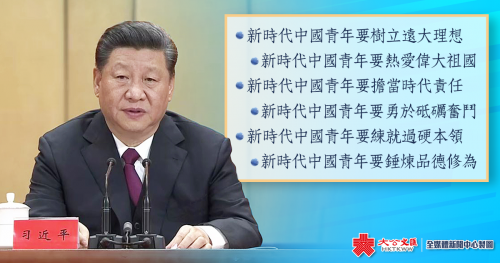

Xi Jinping’s speech was profound and comprehensive, and he spoke of everything from the history of May Fourth to the responsibility of youth today, pointing out that the core of the spirit of May Fourth is patriotism. The country today is ruled by the Chinese Communist Party, taking the path of socialism, and therefore for the youth of China today, loving the country, loving the Party and loving socialism are identical, and they are the only true patriotism.