In his address to a training session for young leaders at the Central Party School on September 3, Xi Jinping spoke of the immense challenges facing the country and the Chinese Communist Party. The language he chose, however, was not “challenge,” “test” or “obstacle.” He spoke instead of “struggle,” or douzheng (斗争), a word that bears the weight of a painful political history — recalling the internal “struggles against the enemy” that tore Chinese society apart in the 1960s and 1970s.

For many still, douzheng invokes not just the need for unity toward common goals, or a can-do attitude, but warns instead of deep and potentially traumatizing division.

It is important to take note, therefore, when a senior Chinese leader invokes the language of “struggle” in a contemporary context, understanding that the choice of discourse at the upper levels of the Chinese Communist Party is rarely ever incidental, and never, ever casual.

Certainly, Xi Jinping has never “struggled” so much. The official Xinhua News Agency notice on his speech at the Central Party School made use of the word a staggering 56 times. What on earth does all of this “struggling” mean?

On one level, Xi’s struggles certainly refer to the objective challenges facing China, which would include the ongoing US-China trade war, weak if not faltering economic growth, deeper international resistance to the country’s global ambitions, and persisting tensions over issues of sovereignty, whether in Hong Kong, the South China Sea or Xinjiang. Xi’s speech – or what we can make of it from the official release – is less specific about these challenges, but earlier People’s Daily messaging on “struggles” in the Xi era are more explicit on these points.

On another level, Xi’s constant “struggling” in the September 3 speech means we should entertain more seriously the possibility that Xi is facing his own real struggles within the Party as he grapples with this substantial list of challenges. His choice of language might be intended to send a tough message to those within the Party who resist his leadership, or attempt to work against his objectives. So this talk of “struggle” could point to fierce internal struggles and squabbles within the Chinese Communist Party. Certainly, if we look back on the past half century, we can see that talk of “struggle” at the official level has often served as a warning to those who might act at cross purposes to those in power, or who might mount criticism or opposition.

At the same time, we should recognize that this recent litany of “struggles” is not some Xi era outlier, as though he is suddenly peppering Party discourse with throwback terminology. In fact, Xi Jinping’s entire tenure thus far has been attended by a rather dramatic comeback of the notion of “struggle,” and this has been formalized within the Party discourse. To illustrate this, we looked not at the word “struggle” alone, but at the phrase “great struggle,” or weida douzheng (伟大斗争), which appeared in Xi’s Central Party School speech but has been even rarer in the history of CCP discourse.

As a number of sources have noted in recent days, this recent speech was “Xi Jinping’s first systematic exposition of the notion of ‘great struggle.’” In point of fact, though, Xi Jinping is the ONLY leader in the reform era to ever to have offered a “systematic exposition” of the notion of “great struggle” — and that in itself is significant.

No previous top leader since the arrest and trial against the Gang of Four and the start of the reform and opening policy in 1978-1979 has used the phrase “great struggle” consistently to denote either external challenges or internal divisions, based on our search of the People’s Daily newspaper. But Xi Jinping has done so, and the speech on September 3, though perhaps noteworthy for its dense use of the word “struggle,” was by no means a fresh occurrence.

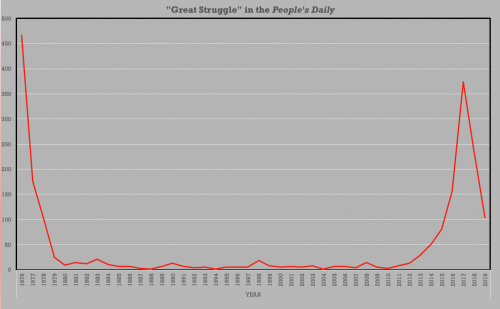

The following graph shows the number of articles mentioning the phrase “great struggle” in the People’s Daily from 1976, starting from the tail end of the Cultural Revolution, during which the notion of struggle was a constant and painful feature of political life. At that time, the “great struggle” was generally directed against the perceived enemies of Mao Zedong, who were often branded as “rightists,” and against the “imperialism” of the United States.

Most often, the enemies to “struggle” against were those within the Party’s ranks and within society. On October 1, 1976, for example, just weeks after the death of Mao Zedong, and just days before Hua Guofeng ordered the arrest of the Gang of Four, an article on page five of the People’s Daily bore the headline: “A Great Struggle Criticizing Deng [Xiaoping] and Counter-Attacking Rightist Tendencies to Promote Film Development” (批邓、反击右倾翻案风的伟大斗争促进电影事业发展). The article was about the release of new films for National Day, many of which dealt with anti-rightist themes.

By April of the next year, four months before Deng Xiaoping’s rehabilitation at the National Party Congress in 1977, the struggle had turned on the Gang of Four. A headline in the People’s Daily read: “Fully Carrying On the Great Struggle to Expose and Criticize the ‘Gang of Four'” (把揭批“四人帮”的伟大斗争进行到底).

Many more articles referring to a “great struggle” with regard to the Gang of Four made their way into the newspaper through 1979. But after this, as reform and opening got underway, the phrase effectively disappeared for more than three decades. In fact, in the almost 35 years between the last “great struggle” attacks on the Gang of Four and the first appearance of “great struggle” in the Xi Jinping era, just two references to the phrase appear at all in the headlines of articles in the People’s Daily, and on average between 1980 and 2011 the phrase appears in just 7.5 articles in the newspaper each year.

In the graph above, the peak during the Xi Jinping era is unmistakable. In 2011, just 8 articles in the People’s Daily mentioned the term “great struggle,” in keeping with reform period averages. In 2012, we see just a slight increase, with 13 articles including the phrase. But in fact, 12 of these 13 articles date to November and December 2012 and refer directly to the language of Hu Jintao’s political report to the 18th National Congress of the CCP, in which he said that, “Developing socialism with Chinese characteristics is a long-term and arduous historical task, and [we] must prepare to carry out a great struggle with many new historical aspects.”

It is no secret that Xi Jinping took the leading role in drafting the political report delivered by Hu Jintao at the 18th National Congress, and this talk of new historical challenges as a “great struggle” is very much in keeping with Xi’s subsequent language about a “new era” and so on. I would argue, then, that we already see the beginning of the Xi Jinping “great struggle” swell in late 2012 during the 18th National Congress.

Through Xi Jinping’s first term, we can see a precipitous rise in use of the phrase “great struggle,” which peaks at 374 articles in the People’s Daily for 2017, thanks in part to the role of the phrase during the 19th National Congress toward the end of that year. During this five-year period, the phrase appears in the context of the anti-corruption drive, as in this article , or this article, both of which talk about the “strict governance of the Party” (从严治党). But the phrase also appears in the midst of warnings about a whole range of perceived risks and threats, both domestic and international — as in this piece written by Meng Jianzhu in February 2017 while he served as head of the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission. Meng writes, echoing the words of the 2012 political report, that “General Secretary Xi Jinping is focused on carrying out a great struggle with many new historical aspects.”

By the 19th National Congress in November 2017, “great struggle” had already become solidified into a new numerical propaganda phrase pushed by Xi Jinping. The so-called “Four Greats” (四个伟大) were about carrying out a 1) “great struggle” (伟大斗争) in order to build 2) “great projects” (伟大工程), promote 3) “great achievements” (伟大事业) and realize the 4) “great dream” (伟大梦想) — the last a reference to Xi’s so-called “Chinese dream” of the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese people.”

But the “Four Greats,” led by the notion of “struggle,” were also deeply enmeshed with the governance of the Party itself, the idea being that a “great rejuvenation” could only be achieved if the Party could remain united around the firm core of General Secretary Xi. As Wang Qishan, the powerful and feared outgoing anti-corruption chief (and soon to be vice-chairman) wrote in an article in the People’s Daily on November 7, 2017: “Comprehensive and strict governance of the Party provides a staunch guarantee for historic change. If our Party is to carry out a great struggle, build great projects, promote great achievements and realize the great dream, it must unswervingly adhere to comprehensive and strict governance of the Party.”

The peak created by the 19th National Congress makes it seem that “great struggle” is already in denouement in 2019. But so far this year, the phrase has appeared in 105 articles in the People’s Daily, and those numbers are likely to remain strong, or even rally, in the final four months of the year, with the 70th anniversary of the PRC — not to mention the very real challenges, tests and obstacles facing Xi Jinping, including unhappiness in Hong Kong, and economic and trade woes.

Xi’s talk of “struggle” this week was an important sign, and one to continue watching. This is true, however, not because these remarks are unusual or surprising, but because they have been normalized as part of the fabric of politics in the Xi Jinping era. The Chinese Communist Party is once again the party of struggle, turning on itself as much as on the problems the country faces.

David Bandurski

CMP Director