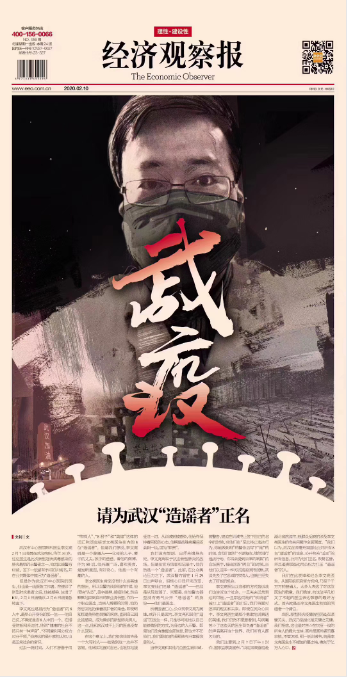

The death of Wuhan doctor Li Wenliang (李文亮) earlier this month set off a wave of anger in China that has presented a major challenge to the leadership in its efforts to control public opinion. In coverage from Party-state media we have seen sometimes sharply contrasting visions of Li Wenliang and how his story relates to the question information control — a central point of contention for many Chinese commenting on social media.

Li, the ophthalmologist from Wuhan Central Hospital (武汉市中心医院) who was infected with the coronavirus while dealing with patients on the front lines of the epidemic, was questioned by his hospital and by police several weeks earlier for warning through social media about the emergence in Wuhan of cases of atypical pneumonia. Add to this the fact that Dr. Li was young, by all accounts amiable, well-educated and enthusiastic about life, and his death becomes for many Chinese, and particularly the networked middle-class, a highly relatable tragedy. On top of all of this, details about the circumstances facing Dr. Li’s family in the wake of his death have again prompted public concern.

Li Wenliang’s death was closely tied with many of the aspects of the treatment of the coronavirus epidemic by the authorities that have left people infuriated: lack of transparency of information, slowness in revealing the situation to the public, and the neglectful treatment of medical personnel. The young doctor’s death came as a shock to many Chinese.

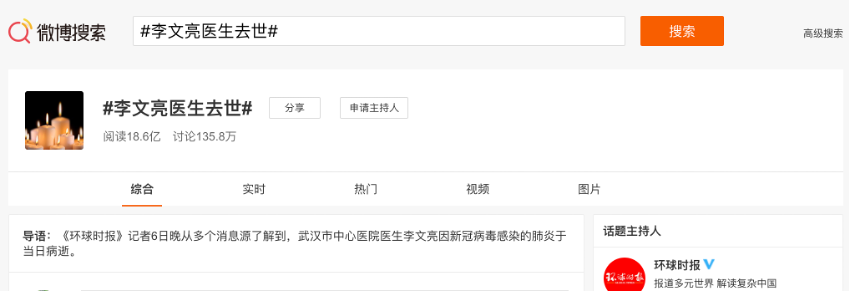

Li Wenliang Timeline

On the night of February 6, a doctor at Wuhan Union Hospital broke the news of Li Wenliang’s death on Weibo. Shortly after, the hashtag “DrLiWenliangPasses” (#李文亮医生去世#) was created on Weibo by the official account of the Global Times, a newspaper published under the umbrella of the People’s Daily. The account offered the following introduction:

A Global Times journalist learned on the night of February 6 from numerous information sources that Wuhan Central Hospital doctor Li Wenliang has passed away from pneumonia resulting from the coronavirus.

After this, there were purported refutations of the news, suggesting it was a rumor and that Li Wenliang was still being urgently treated. The exact time of Li Wenliang’s death became a topic hotly discussed by internet users, again prompted deep and widespread distrust of official Party and government information channels.

On the afternoon of February 7, the National Supervisory Commission, the country’s top anti-corruption body, announced its decision to dispatch a special investigative team to Wuhan, with approval from the Central Committee, to “conduct a full investigation into public complaints about problem relating to Dr. Li Wenliang.” This announcement, essentially signaling that the central leadership was aware of the serious repercussions of Li’s death, effectively gave Chinese news media a “protective amulet” (护身符) that would allow for related coverage, at least for a brief window of time.

The following is a basic timeline of the breaking of the news of Li Wenliang’s death and the official media response.

As Anger Rises, Central and Provincial Party Media Follow Suit

Looking at coverage of the death of Li Wenliang in newspapers across the country from February 7 to 9, we can find the following central Party media reporting on Li’s death: People’s Daily, People’s Daily (Overseas Edition), the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Journal, Economic Daily, Legal Daily, Procuratorate Daily, China Discipline Inspection Journal and Xinhua Daily Telegraph.

The story was not reported by People’s Liberation Army Daily or by Guangming Daily, the former published under the Political Department of the PLA and the latter by the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department.

Looking then at provincial-level CCP newspapers, those published directly by the Party committees of various provinces, we find most papers reporting in some way on the Li Wenliang story, with the exception of Shanxi Daily, Xinjiang Daily and Tibet Daily. The following table shows all provincial and municipal-level newspapers and their commercial spin-offs, including only those that did report the story of Li Wenliang’s death.

| 地区 | 报纸数(家) | 刊发李文亮相关报道的报纸 |

| 北京 | 4 | 北京日报、北京晚报、新京报、北京青年报 |

| 上海 | 5 | 解放日报、新民晚报、新闻晨报、文汇报、青年报 |

| 天津 | 2 | 天津日报、今晚报 |

| 重庆 | 2 | 重庆日报、重庆晨报 |

| 广东 | 15 | 南方日报、广州日报、中山日报、梅州日报、潮州日报、佛山日报、湛江日报、宝安日报、南方都市报、珠海特区报、深圳晚报、深圳商报、深圳特区报、信息时报、羊城晚报 |

| 江苏 | 14 | 新华日报、南京日报、常州日报、徐州日报、泰州日报、无锡日报、吴江日报、丹阳日报、启东日报、如皋日报、扬子晚报、常州晚报、江南晚报、金陵晚报 |

| 湖南 | 10 | 湖南日报、湘潭日报、郴州日报、益阳日报、株洲日报、衡阳日报、衡阳晚报、潇湘晨报、三湘都市报、湘西团结报 |

| 浙江 | 9 | 浙江日报、杭州日报、绍兴日报、湖州日报、丽水日报、余姚日报、每日商报、绍兴晚报、都市快报 |

| 河南 | 8 | 河南日报、郑州日报、开封日报、洛阳日报、平顶山日报、洛阳晚报、汴梁晚报、京九晚报 |

| 山东 | 7 | 大众日报、青岛日报、潍坊日报、菏泽日报、淄博日报、联合日报、烟台晚报 |

| 广西 | 7 | 广西日报、桂林日报、梧州日报、右江日报、柳州日报、玉林日报、西江都市报 |

| 山西 | 5 | 山西晚报、长治日报、大同日报、太原日报、太原晚报 |

| 福建 | 5 | 福建日报、福州日报、闽北日报、厦门日报、湄洲日报 |

| 辽宁 | 5 | 辽宁日报、大连日报、大连晚报、辽沈晚报、沈阳晚报 |

| 四川 | 5 | 四川日报、德阳日报、南充日报、凉山日报、成都商报 |

| 贵州 | 5 | 贵州日报、遵义日报、黔南日报、贵州都市报、贵阳晚报 |

| 陕西 | 5 | 陕西日报、咸阳日报、榆林日报、华商报、文化艺术报 |

| 青海 | 5 | 青海日报、格尔木日报、西宁晚报、西海都市报、海东时报 |

| 安徽 | 4 | 安徽日报、合肥日报、安庆日报、安徽商报 |

| 宁夏 | 4 | 宁夏日报、银川日报、中卫日报、银川晚报 |

| 湖北 | 3 | 湖北日报、三峡日报、襄阳日报 |

| 甘肃 | 3 | 甘肃日报、兰州日报、兰州晨报 |

| 河北 | 2 | 河北日报、张家口晚报 |

| 吉林 | 2 | 吉林日报、长春日报 |

| 江西 | 2 | 江西日报、赣南日报 |

| 云南 | 2 | 云南日报、都市时报 |

| 海南 | 2 | 海南日报、南国都市报 |

| 内蒙古 | 1 | 内蒙古日报 |

| 黑龙江 | 1 | 黑龙江日报 |

Much coverage of Li Wenliang molded his story into the normative CCP narrative of heroism and personal sacrifice, sidestepping the uncomfortable issue of his mistreatment by local authorities, and the fact that his openness in addressing the coronavirus epidemic contrasted sharply with the Party’s own whitewashing of the story through much of January.

On February 8, CCTV-1 broadcast its “2020 Lantern Festival Special Program” (2020年元宵节特别节目) corresponding with the final day of the annual Spring Festival. As the anchor narrated a segment called “What You Look Like” (你的样子), the following black-and-white image of Dr. Li Wenliang’s flashed by on the screen, treated as a “white angel of sacrifice” laying down his life for the lives of others.

On February 10, the People’s Daily, Xinhua Daily Telegraph and Guangming Daily all ran the same review of the CCTV-1 program two days earlier, mentioning that “Li Wenliang, Song Yingjie and other doctors, and the heroic group portrait of police officers such as He Jianhua, Li Xian, Cheng Jianyang, Yin Zuchuan and Liu Daqing . . . had flashed across the big screen, bringing countless audience members to tears.”

Outstanding Pages and Commentaries

But there were also notable articles and page designs that put Li Wenliang’s story in a different light, stressing his role as a “whistleblower,” and his remarks about the need for diverse voices in a healthy society.

Below is a “special report” that appeared in the February 8 edition of Guangzhou’s Southern Metropolis Daily, a commercial spin-off of the official Nanfang Daily newspaper. The cover includes a central image of flowers left in memory of Li, with a headline that read, alluding to Dr. Li’s posting on WeChat about the epidemic in early January: “Epidemic ‘Whistleblower’ Li Wenliang Passes Away.”

A number of front pages included the now famous image of Dr. Li wearing a protective face mask and staring straight into the camera. The February 7 front page of the Xinmin Evening News, a newspaper published in Shanghai under the state-owned Shanghai United Media Group (SUMG), included this photo in a black frame box, with the headline: “Farewell, Dr. Li Wenliang: So This is the Kind of Person He Was.” A commentary below, designed with commemorative burning candles below, was called, “Letting Openness, Transparency and Sunshine Break Through the Fog of Disease.”

A commentary in the Arts and Culture Journal (文化艺术报), “Remembering Dr. Li Wenliang is to Give Treatment to Ourselves,” included a pencil sketch of Dr. Li shared to various social media platforms in China. The commentary dealt directly with the issue of openness of information as a key component of a healthy society, even including a quote from Li Wenliang during a February 1 interview with Caixin Online: “A healthy society cannot have just one voice” (个健康的社会不该只有一种声音).

The following are pages from Yinchuan Evening News (银川晚报) and Shanxi Evening News (山西晚报). At left, the Yinchuan Evening News story is quite explicit in is rejection of overwrought notions of heroism, and emphasis on the “ordinary person.” The large headline reads: “There are No Heroes Who Drop Out of the Sky, Only Ordinary People Who Step Up.” Li is referred to on both pages as a “whistleblower,” or “’whistleblower’ Li Wenliang.”

The very notion here of the “whistleblower” – particularly in contrast to heroic narratives – is a slight provocation, a recognition that in order to uphold his professional responsibilities and basic conscience Li Wenliang had to act against the impulses of a system that worked to keep him quiet.

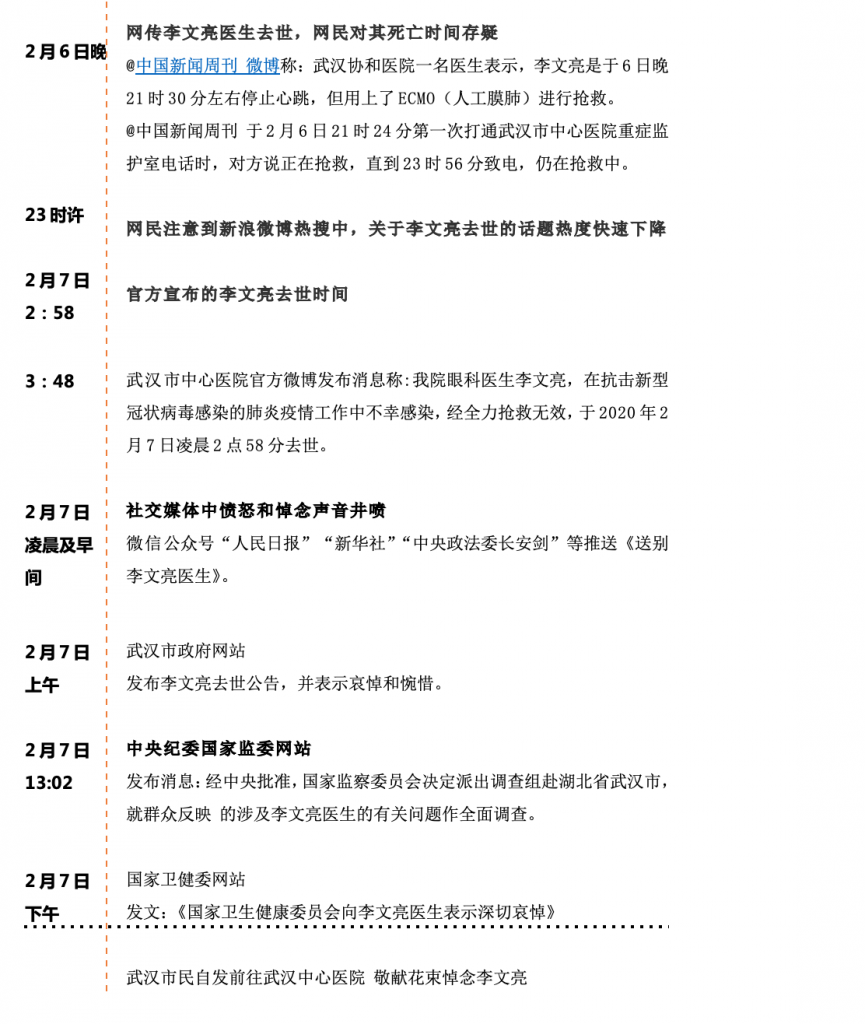

But one of the most evocative front pages came from the Economic Observer, a prominent business newspaper. The page was dominated by a dark image of Li Wenliang, rendered in grey and earthy tones, with a pair of bold, martial arts inspired characters that read: “Battling the Epidemic.” The sense was of Li as a popular hero, as opposed to the abstracted sacrificial character of CCP propaganda. The headline of the text below the image, against an oval design resembling the coronavirus, read: “Please Clear the Name of Wuhan’s ‘Rumor-Monger’”.

The article referred to the now infamous letter of admonishment that Li Wenliang was forced to sign by local police in Wuhan confessing the error of his decision to shared information about the dangers of the coronavirus outbreak. The Economic Observer again shared the Li Wenliang quote from Caixin Online: “A healthy society cannot have just one voice.”

The following are translated portions of several articles, including the papers in which they appeared. They provide an interesting, if sometimes subtle, criticism of official narratives of abstracted “heroism” against genuine respect and protection of flesh-and-blood human beings committing simple acts of conscience.

“Forever Bearing in Mind the Weight of the World ‘People’” (永远牢记“人民”二字的分量)

Liberation Daily (Shanghai), February 8, 2020

Remembering Li Wenliang means a full and thorough investigation to respond to the most direct concerns and confusions of the public, letting the truth open the fog, using actions to provide answers – this is a consolation to Li Wenliang, and a consolation to all the good people who care for him and grieve for him. Remembering Li Wenliang also means respecting and protecting more Li Wenliangs, offering thanks and respect to the countless Li Wenliangs. This is not necessarily a tribute to “heroes,” but a tribute to the “people.”

“Remembering His Justice and Courage” (记住他的正义和勇气)

Nanfang Daily, February 8, 2020

Looking back now, his acts, whether from a medical perspective or from the standpoint of the interest of society, were doubtless acts of responsibility, warning signs given out of professionalism. He is a true hero. As a number of experts have said: “Commenting after the fact, we can give them the highest marks.” . . . . “The facts have shown that faced with an unknown and complicated epidemic disease, it is more responsible to treat small seedlings with an attitude of respect.”

“The ‘Whistleblower’ Has Gone: The Truth Should Remain” (“吹哨人”走了 真相应永驻)

Yangcheng Evening News, February 8, 2020

Those who embrace the public should not be left to freeze in the snow. Those who hold up a candle for the world should not be allowed to disappear into the night. Speaking truthfully, this is the basic ethics of any normally functioning society, and the cornerstone of maintaining fairness and justice. In the face of this epidemic, questions cannot be addressed only to this or that individual, or to certain [government] departments – we must all face them. In the swipe of the mobile era, grief and oblivion seem to come and go so quickly. But I hope we always remember him: Li Wenliang, the doctor and ‘whistleblower’ struck down so unfortunately by the epidemic.”

Two Embassies, Varying Opinions

The attitude toward the death of Li Wenliang in official circles, as glimpsed through media coverage on February 10, remained deeply divided, with an admixture of pragmatism.

On February 10, Shanghai’s Wenhui Daily ran a piece called, “Chinese Ambassador to the U.S. Introduces China’s Epidemic Fight on PBS News Program, Says ‘This is a Tough Struggle We Are Confident We Will Win” (similar foreign ministry release). Perhaps with a thought to accommodate the feelings of his American audience, Cui Tiankai was actually quite moderate during his interview toward Dr. Li Wenliang, saying that “we encourage speaking the truth.” The story read at one point:

Cui Tiankai emphasized that we encourage speaking the truth. Perhaps at the start not everyone understands and accepts these people who speak the truth, and such things could happen in any place, but we encourage people to speak the truth, and to face challenges head on. Only those who don’t speak the truth and who don’t face challenges head on will be punished.

Cui Tiankai’s remarks, however, were quite different in tone to a piece released on February 9 through official WeChat account “Chinese Embassy In France.” The piece, called “Using Unity and Victory to Say Goodbye to Dr. Li Wenliang” (用团结和胜利告慰李文亮医生), was quite stern in its words for Chinese living in France who were voicing opposition in the wake of Li’s death. It said:

There are certain people with ulterior motives (别有用心的人) using the memory of Li Wenliang as an excuse to agitate overseas Chinese and overseas students in France who care about the epidemic and organize a so-called “Tonight, We Whistleblow for Truth” (今夜,我为真相吹哨) event. Everyone must know that “whistleblower” (吹哨者) was originally a derogatory term meaning someone who is an informer or undercover. When they use this word to describe Li Wenliang, this attaches to him a political label, with bad intentions, the goal being to divide Chinese opinion, and this spoils the reputation of Dr. Li Wenliang and it is immoral. . . . At this time, we need to think and decide cool-headedly, clearly separating those voices truly made out of a sense of justice and conscience, and those that are using our feelings of pity to obscure the facts and incite anger and hate in order to sow chaos in people’s hearts and destabilize the overall situation. Before our great enemies, we must prioritize the overall situation and not be self-defeating . . .

On February 10, the Study Times journal published a commentary called “Public Opinion Phenomenon of Skidding After Snow Deserves Study” (舆论雪后打滑现象值得研究), which expressed the view that the turbulent public opinion following Li Wenliang’s death was a treacherous (like an icy path) battle of ideas. It echoed the view expressed by the Chinese Embassy in France that unified calls around Li Wenliang’s death were a conspiracy to confuse and sow chaos:

In the battle for public opinion, the situation is far more complex, the enemy is often not even visible, and the front-lines cannot be made out clearly. If we do not maintain clear positions and rational thinking . . . . it will be difficult to avoid being engulfed in public opinion, becoming the passenger on the public bus skidding after the snow.

On social media, the talk of conspiracy was often even clearer. The views of a purported officer within the Public Security Bureau posted to WeChat (of unclear origin) and shared widely suggested that in view of the urgency of the epidemic and other problems facing China, public opinion had to be controlled, and sources of information must be centralized:

Right now the country faces an extremely complicated and severe situation, whether this is about facing domestic pressures or external pressures, or about facing the pressure in terms of the epidemic, production, food, supplies, public opinion, economy, finance, diplomacy, the military . . . . and so on. We can say the pressure is on all levels, and if any link experiences a problem this could have a serious chain reaction, creating a domino effect, and the consequences would be unimaginable! National security is the interest of the people. . . . .

The world is not so peaceful and harmonious as ordinary people generally think, and the more the country faces danger the more rumors fly, because the precision public opinion attacks from external forces begin, just as we’ve seen in Hong Kong. If the government loses its credibility and discourse power then it has taken irreversibly to the road of national decline! Why does public opinion choose Dr. Li? Because he is young, handsome, motivated and kind, and he is all the more capable of inspiring the sympathies of ordinary people, and more capable of stirring up public opinion . . . .

This post expressed concern at the intense criticism facing the police as a result of Li Wenliang’s treatment by police in Wuhan, and speculated that this could become a source of broader instability incited by vague “external forces”:

Fingers are now pointing at the Public Security Bureau over the epidemic, with criticism everywhere . . . . If they [the police] lose heart and forfeit their ability to maintain control, it is conceivable that the external forces will conduct their precision attacks with the intention of replicating the Hong Kong model!

These diverging views are of course not at all unfamiliar. On the one hand, the view that information openness is a crucial aspect in any society, and that the voices of professionals, journalists and all manner of ordinary people must be heard as a matter of basic health and social well-being. On the other hand, the view that public opinion is a toxic and destabilizing force, manipulated by hostile “external forces,” that must be controlled as an urgent matter of national security (overlaid, of course, with the question of regime security). The same divergence of views within the leadership and within official media emerged in the midst of the 2003 SARS epidemic.

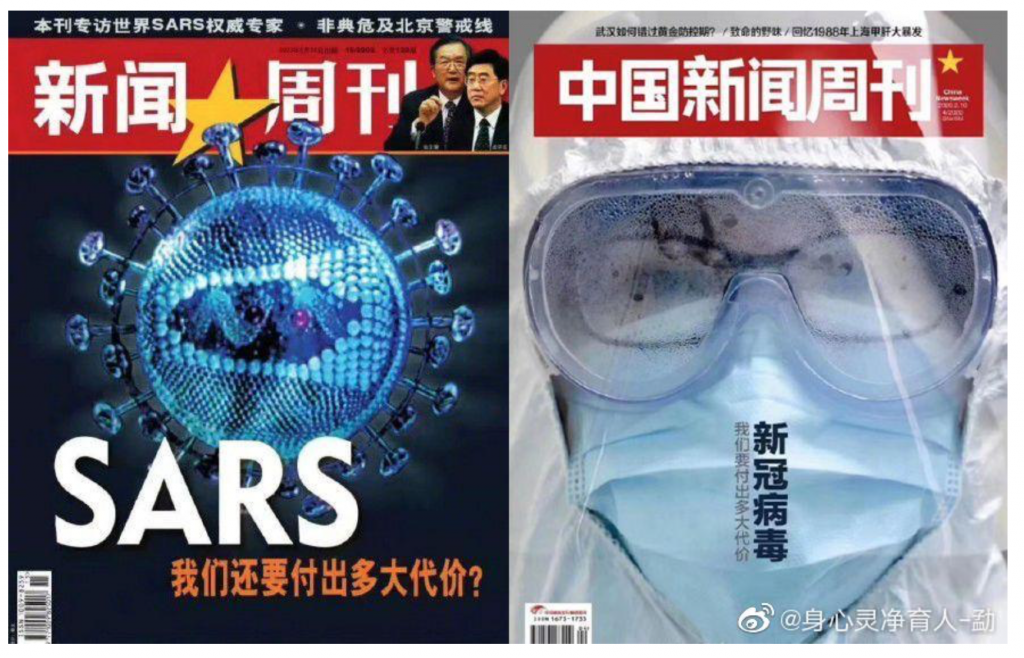

In the light of the Li Wenliang case, many Chinese have noted the frustrating familiarities. It has been 17 years since the SARS epidemic, which at that time prompted soul-searching about the role of openness and information in dealing with issues of immediate public concern. And yet, some ask, have the costs of information secrecy and public opinion control changed?

One Chinese internet user commented on the frustrating lack of apparent progress between 2003 and 2020 by sharing side-by-side two covers of China Newsweekly, a leading news magazine. The first, dating back to 2003, bore the cover story: “SARS: What Price Must We Still Pay?” The second, from this month, bore the almost identical title: “Coronavirus: What Price Must We Pay?”