Xi Jinping took part yesterday in a video teleconference with G20 leaders to address the coronavirus epidemic. The news is reported prominently on the front page of today’s People’s Daily, just below the masthead. The headline, running vertically alongside an image of Xi, emphasizes his role in the teleconference: “Xi Jinping Attends G20 Leaders Special Summit on New Coronavirus and Delivers Important Speech.”

What was this “important speech”? It was called, “Working Together to Fight the Epidemic” (携手抗疫 共克时艰). China’s deputy foreign minister, Ma Zhaoxu, summarized Xi’s speech, saying that its chief purpose was to introduce “China’s experience,” set forth “China’s proposition,” put forward a “Chinese initiative,” and outline pledges for “China’s contribution.”

Ma praised the speech for “adhering to the concept of a community of common destiny for mankind,” a reference to Xi Jinping’s key foreign policy phrase. He said the speech “integrated China’s practical experience in fighting the epidemic, laying out a series of important propositions, and playing an important guiding role for strengthening international cooperation on epidemic control and stabilizing the global economy.”

In fact, Xi Jinping’s speech was incredibly brief, consisting of just 1,411 Chinese characters. Particularly of note is the fact that just a small portion of the speech, about 106 characters, or seven percent, deals with China’s experience at all. Here is what that section, found right at the outset of the speech, actually says:

Faced with the sudden rise of the novel coronavirus epidemic, the Chinese government and the Chinese people did not shrink from adversity, but placed people’s lives and health above all. With firm resolution, mutual aid, scientific prevention and precise policies, we undertook a people’s war against the epidemic through national mobilization, joint prevention and control, and openness and transparency.

During his inspection tour in Beijing on February 10, Xi Jinping used the terms “people’s war” (人民战争), “total war” (总体战) and “battle” (阻击战) to describe the challenge facing China. All three of these terms appeared in the most prominent headline in the next day’s edition of the People’s Daily.

This trinity of terms has been central to sloganeering in official propaganda in the midst of Xi’s “war” against the coronavirus epidemic. The terms have been used in concert through February and March as successive Politburo Standing Committee meetings have been held, and as Xi visited the city of Wuhan, the epicenter of the epidemic.

During the G20 video teleconference, as Ma Zhaoxu tells us, Xi introduced “China’s experience,” using the term “people’s war,” a term going back to Mao Zedong. As Xi Jinping addressed the global response, he also spoke of a “battle,” or zujizhan (阻击战), using another term in his anti-epidemic trinity.

But the third term in the trinity, “total war,” or zongtizhan (总体战), was missing from Xi’s G20 speech. Why would this erstwhile crucial term suddenly be dropped? My guess is that the speech writer, having some knowledge of world history, made necessary adjustments. Why? Because speaking of “total war” before the leaders of the United States, the UK, Germany, France and Russia could invoke shades of the Second World War and seem completely out of context.

For China’s leaders, talk of “total war” may sound determined and resolute. But the phrase, in fact, is not a positive one. It is generally attributed to general Erich Ludendorff, Germany’s chief military leader during the First World War, whose ideas, some have said, “paved the way for Hitler,” and who has been called “the first Nazi.”

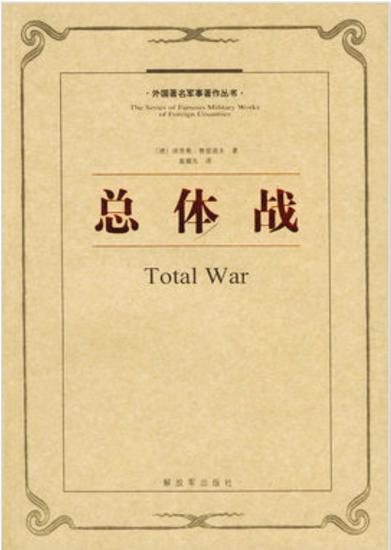

Below is an image of the cover of a Chinese translation of Ludendorff’s 1935 book Total War.

And here is an image of Ludendorff standing alongside Hitler, taken in Munich in April 1935 to mark Ludendorff’s 70th birthday. Hitler had ordered celebrations of the day across Germany, and the general was, according to the New York Times, “officially restored to the ranks of Germany’s heroic figures.”

The notion of “total war” meant that a nation would mobilize all available resources for the purposes of war. The term came into wider use in 1943 as the situation in the Second World War took a dramatic turn. The German army was defeated at the Battle of Stalingrad, which began in September 1942 and lasted for several bitter months, and suffered grave setbacks in other key engagements. Finally, on February 18, 1943, Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda, delivered his infamous “Sportpalast speech” during which he called for “total war,” urging the German people to continue the war at all costs in order to turn back the threat of Bolshevism.

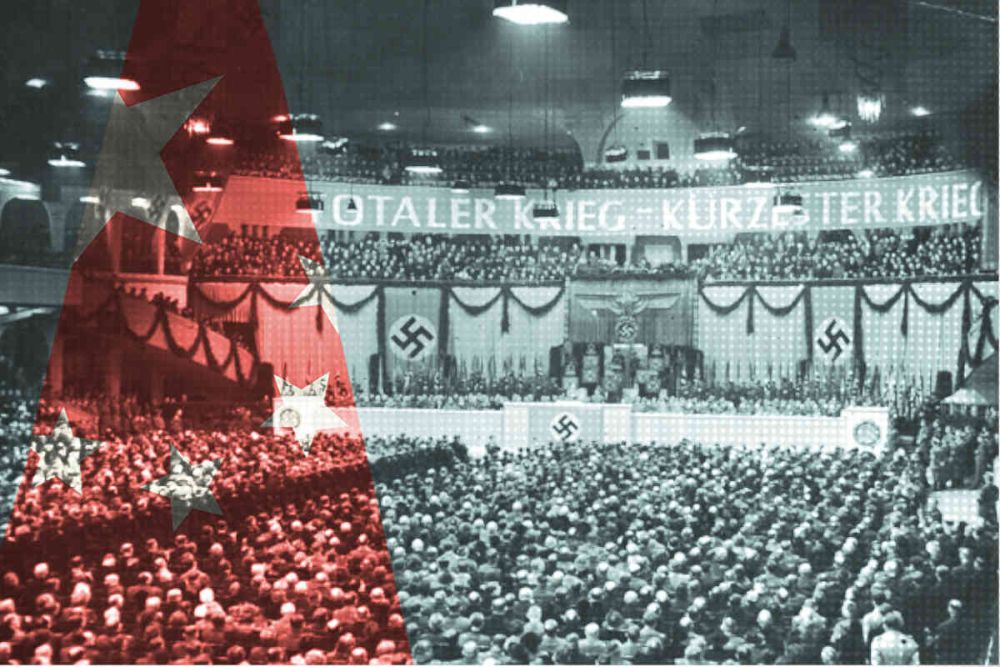

The term seen here on the banner flying over the grand stage at the Berliner Sportpalast in February 1943 – “total war,” or Totaler Krieg – is the very same word as the Chinese zongtizhan (总体战) that has formed part of Xi’s trinity of anti-epidemic slogans since last month.

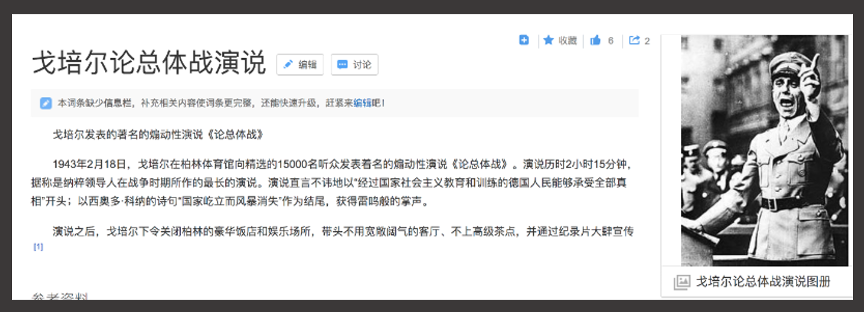

Search for information on “total war” in the Chinese search engine Baidu, and you quickly come to the following entry on Goebbels’ speech, which also notes that “after the speech Goebbels ordered the closure of luxury hotels and entertainment venues in Berlin.”

Within the discourse of the Chinese Communist Party, the “people’s war” is a now classic “red discourse” (红色词语), but in fact “total war” has always been what can be called “black discourse” (黑色词语), associated with capitalism and capitalist forces. In educational texts for national defense, the theory of “total war” is rejected as “an important guiding ideology of the imperialists in engaging in war,” as can be seen in the following image of related online study materials from the Ministry of Education.

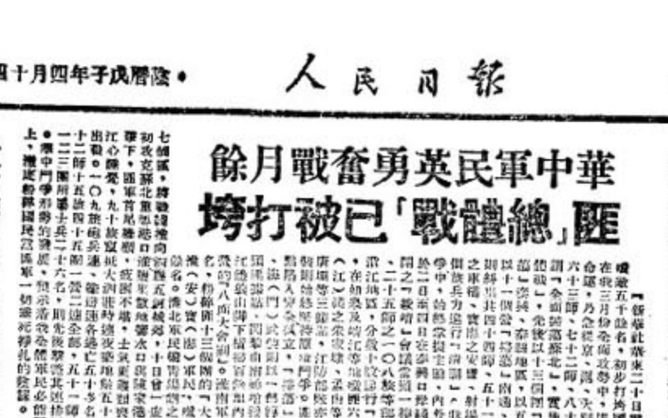

In 1948, as the Chinese Communist Party and the Kuomintang Party were locked in a bitter civil war, the People’s Daily, which had been launched two years earlier, ran a report with the headline: “After a Month of Brave Fighting By Liberation Army Soldiers in Jiangsu, the ‘Total War’ of the [KMT] Bandits Has Been Shattered.”

This history of “total war” was the reason for my astonishment as I spotted the term in the front-page headline in the People’s Daily on February 11. I’m sure others like me who are familiar with the discourse of the CCP felt exactly the same way.

In recent years under Xi Jinping, many old Maoist terminologies have been dusted off and given new life – phrases like, “East, south, north and center, Party, government, military, society and education – the Party rules all” (东西南北中,党政军民学,党是领导一切的). At the same time, a number of former “black words” seem to have been rehabilitated and appropriated – phrases like “in the highest position” (定于一尊), once decadent and imperial but now a positive expression of the lofty power of the top leader.

The simplest explanation for this inconsistency is the fact that in the so-called “New Era,” the functionaries in charge of penning speeches and official documents are not as sensitive as they once were to the CCP’s own history, much less to world history. They have no direct experience of Mao era, nor do they necessarily have a very deep sense of the early reform era under Deng Xiaoping. This has led to the absurd situation – absurd according to the internal logic of CCP discourse – that we find black words mixed into with the red.

In the case of Xi’s G20 video teleconference speech, the “total war” once shouted out by Goebbels cannot be found. But this does not mean the term has been shut out in the cold. A separate commentary in the People’s Daily today again chants the trinity on the new priority of getting the economy humming again, asserting that “the active and orderly return of production . . . concerns comprehensive victory in the people’s war, total war and battle to contain and control the coronavirus epidemic.”

“Total war’ is almost certainly missing from Xi Jinping’s G20 speech out of recognition of its potential sensitivity in this context. The important question now is whether and how Xi Jinping might continue to use this dangerous phrase domestically — even long after the war against the epidemic has been won.