A propaganda poster from the 1950s depicts the PRC’s hope for rapid industrialization as a result of its Five-Year Plan.

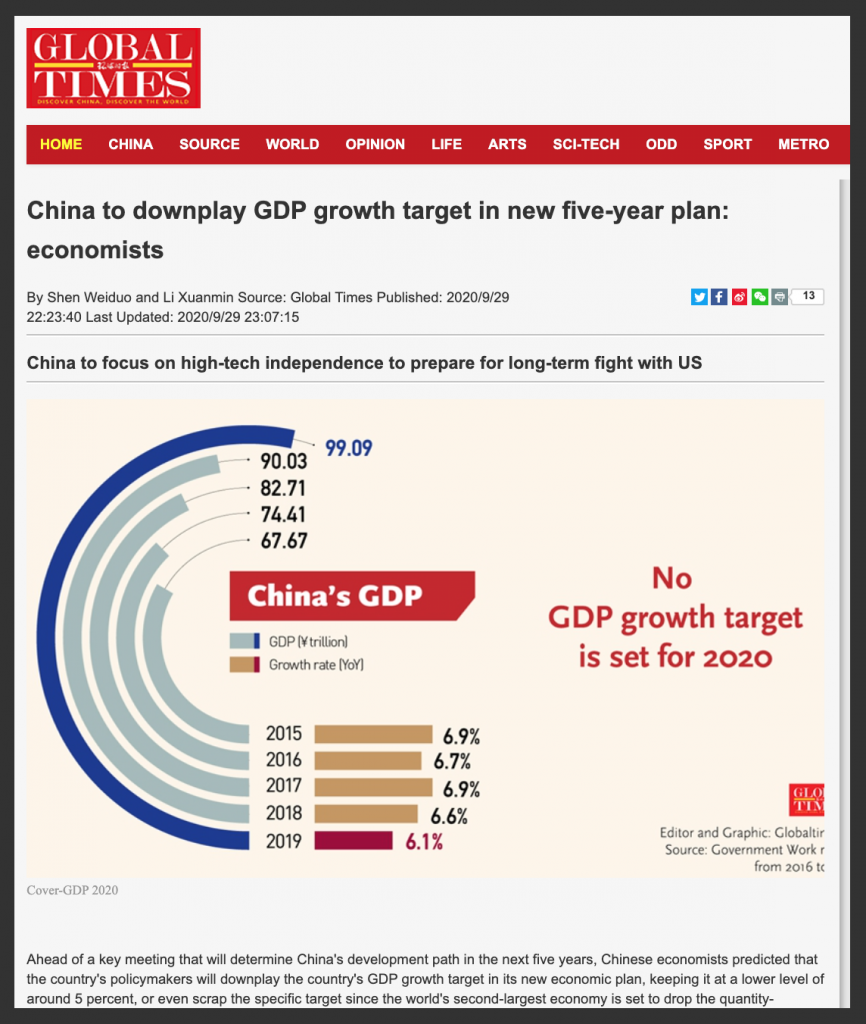

The Chinese Communist Party’s Fifth Plenum, which kicked off in Beijing on Monday, has focussed this week on an assessment of the most recent 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) – with fulsome propaganda for the “historic progress” achieved by Xi Jinping – and discussion of the proposed 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for economic and social development.

Why should this meeting, and this new plan for national development, matter to the rest of the world?

There are any number of reasons to tune in when it comes to the economic and investment impact, as well as geopolitical ramifications. The crux of the new plan, more details hinging on the “bulletin,” or gongbao (公报), that will be released tomorrow (Thursday), will likely be a recognition that China faces a “considerably less benign” global trade landscape than in the past, necessitating greater self-reliance. China’s response to these challenges could have broader ramifications worldwide. There is also the issue of the environment. As Reuters has reported, planners are now under pressure to include “radical climate targets” in the 2021-2025 plan following Xi Jinping’s pledge to the United Nations to make China carbon neutral by 2060.

But as China’s medium and long-term goals come into focus this week, it is equally important to look beyond the targets, benchmarks and pronouncements and bear in mind that the CCP’s five-year plans are much more than simple plans. They are, importantly, statist visions of how planning should be done, and as such they are bold statements about the nature of political power and its relationship to society.

China’s five-year plans have their origins in the piatiletka of Stalin’s Soviet Union, first launched in 1929 as a program of rapid industrialization that focused on heavy industry and the collectivization of agriculture. Stalin’s first five-year plan, launched in response to perceived external threats, was by some measures a success, resulting, as one scholar later termed it, in a “creative surge” of economic activity that “covered the immense country with building sites, factories and dams.” But it was also a “state-guided social transformation” that tore society asunder, a “revolution from above” that placed the Communist Party of the Soviet Union at the center of all aspects of life – social, economic and political.

While the nature of economic planning has of course changed since China’s first five-year plan, following the Soviet example and with Soviet input, was kicked off in 1953, the central role of the Communist Party has not changed. In this sense, the Fifth Plenum is not about goals met and goals set, but more essentially about renewing the CCP’s claims to the legitimacy of its power, its system and its methods.

International news breakdowns like this one from Reuters may dwell on policy priorities like innovation and domestic consumption, but in the Party-state media the centrality of power and legitimacy are impossible to overlook. An article pinned to the top of People’s Daily Online Monday, as the plenum began, bore the headline: “The ‘Five-Year Plan’ Enacts the Unique Charm of ‘Chinese Governance.’” The article focussed on the five-year plan not just as a “significant milestone in measuring China’s pace” and progress, but as a core aspect of China’s unique system of governance. Each planning period, it said, had marked a progressive path on which the Chinese people first “stood up,” then grew rich, and then, finally, became powerful. “In this process of hard work and plodding forward,” the article said, “‘Chinese governance’ has become more and more mature, and the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation has become nearer and nearer.”

The catchphrase “Chinese governance,” or zhongguo zhi zhi (中国之治), first emerged in 2017, and gained greater prominence in the discourse of Party-state media particularly around the Fourth Plenum in November 2019. It is closely associated with the homophone “the Chinese system,” also zhongguo zhi zhi (中国之制). Together, they express the basic idea that China has developed its own, uniquely effective, system of governance. This week, China’s five-year plan is being showcased in official propaganda as a core aspect of the genius of this uniquely Chinese system (Stalinist origins notwithstanding).

An article from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), reposted Monday at China News Service and many other sites, was called, “The Secret Code of Chinese Governance: The Five-Year Plan” (中国之治的重要密码: 五年规划). The article ran through a brief history of five-year plans, noting changes along the way. In 2006, for example, the word “plan,” or jihua (计划), redolent of the era of the planned economy, was dropped in favor of the less politically loaded term guihua (规划), or “program.” The article then argued for the uniqueness of the five-year plan as an aspect of “Chinese governance”:

The formulation and implementation of the five-year plan for national economic and social development is an important way for the Party to govern the country and an important ‘secret code’ for Chinese governance. Since the founding of the new China more than 70 years ago, and especially since reform and opening, long-term strategies, medium-term programs and annual deployments have been organically combined and complementary methods having a crucial role in promoting the sustained, rapid and healthy development of our country’s economy and society.

Party-state media are also hammering home – lest anyone forget – the core and indispensable role of the CCP in this system of Chinese governance. As the People’s Daily related Tuesday: “General Secretary Xi Jinping has pointed out: ‘The leadership of the Chinese Communist Party is the essential distinctive feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics, and it is the greatest advantage of the system of socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

In this system, the Party’s power is the essential, irremovable heart, and the genius behind its five-year programs. As the People’s Daily article elaborates in the next passage, the capacity of the CCP relies on the genius of its “core” leader, Xi Jinping. “Through five years of hard work, the most fundamental reason ‘Chinese governance’ can open new horizons is the strong leadership of the CCP Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping at the core, promoting the continuous transformation of institutional advantages into governance efficiency.”

Here, beyond the goals and benchmarks, we have a sequence of nesting dolls taking us further into the heart of Chinese politics. Beyond the outer truth of the capacity and efficiency of “Chinese governance,” the “Chinese system” and the five-year planning approach, one finds the system of socialism with Chinese characteristics; within the system of socialism with Chinese characteristics one uncovers the indispensable leadership of the Chinese Communist Party; and at the core of the CCP one finds the incomparable leadership of Xi Jinping himself.

The most important revelation here at the core of the nesting dolls of CCP rhetoric is that the entirety of “Chinese governance” and the “Chinese system” is invested in a single, powerful man. In this sense, the “system” is not emulable in any real sense – even as we are told in the Party-state press that its “institutional advantages” (制度优势) offer inspiration to the world.

This week we can expect to be inundated with declarations of the efficiency and long-term vision of the Chinese Party-state, of the superiority of “Chinese governance” and the “Chinese system.” The self-congratulation began weeks ago, in fact. Earlier this month, China Society News, the official publication of the Ministry of Civil Affairs, ran an article by the ministry’s deputy head, Zhan Chengfu (詹成付), that argued – though there was no reasoning beyond acceptance – for the superiority of the Chinese system as a means of democratically representing the interests of the people.

Zhan began:

General Secretary Xi Jinping has emphasized that the preparation and implementation of the five-year plan for national economic and social development is an important way for our Party to govern the country. Since the founding of New China, from 1953 to 2020, our country has implemented 13 five-year plans or programs, one after another every five years, and these have borne witness to the ups and downs of China’s modernization. With its magical power, the ‘Five-Year Plan’ has ushered in more and more surprises to China and the world, bringing out the unique and tremendous charm of the Chinese system and Chinese governance.

Zhan’s talk of “magical power” perhaps gets closer to the reality of the CCP view of planning, but he continues with a familiar argument about the “long-term” visions and “efficient” allocation of resources. Given these advantages, Westerners can only cast their gaze on China with envy. “Foreign scholars have lamented,” he writes, “that while China is drawing up plans for the next generation, Western countries are planning only for the next election.”

To further support this idea, Zhan offers a quote he attributes to former French prime minister Dominique de Villepin: “Former French prime minister De Villepin once said: ‘China’s concentration of strength and long-term determination to struggle is what Western countries lack.’”

How is it, Zhan asks, that the CCP and the Chinese government can “move from one task to another, passing the baton along, following their blueprints through to the end”? There are two reasons, he concludes. And those reasons will probably not surprise. First, there is the “advanced nature of the Chinese Communist Party.” Next, there are the “significant advantages of the leadership system of the Chinese Communist Party.”

We are running in ellipses of rhetoric, orbiting Xi Jinping and his CCP. As Xi has regularly re-asserted, echoing Mao Zedong: “East, west, south, north and center, Party, government, military, society and education – the Party rules all.” And the Party rules nothing so sternly as its own self-image. Bear that in mind this week as its plans emerge.