Image by Andreas Eldh, available at Flickr.com under CC license.

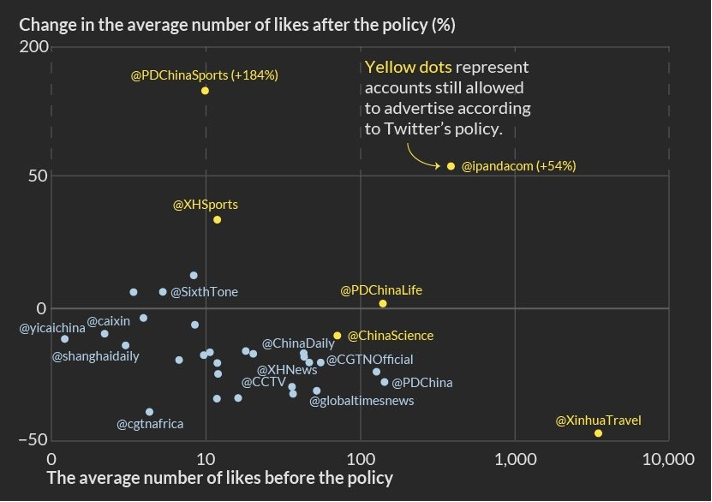

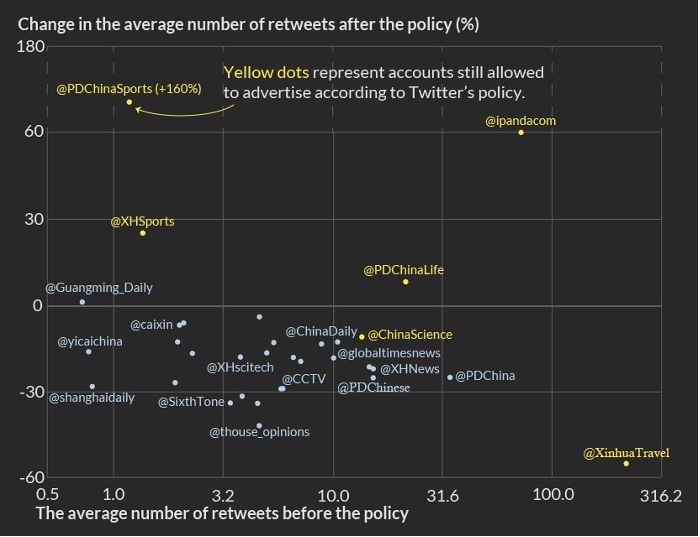

Twitter users are liking and sharing fewer tweets by Chinese news outlets since the social media platform started labeling them as state-affiliated, an analysis by the China Media Project shows.

Comparing tweets from a sample of 33 official Chinese accounts on Twitter for 50-day periods immediately before and after the implementation of the new policy in August 2020, CMP found that tweets by most of the accounts studied showed significantly fewer shares and likes.

The three accounts with the most followers, belonging to state broadcaster CGTN, state news agency Xinhua, and the People’s Daily, the flagship newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party, all saw drops of over 20 percent per tweet. The numbers for China Daily and the Global Times, English-language newspapers published by the Information Office of the State Council and the People’s Daily respectively, also shrank by double digits. Tweets by the latter, a national tabloid long known for its often provocative comments on world affairs, received 31 percent fewer likes after the labeling.

Twitter introduced labels for state media and government accounts on August 6, 2020, with the goal of “providing people with context so they can make informed decisions,” according to a company announcement of the policy at the time. The announcement said the company would begin, in the interests of “transparency and practicality,” with the five countries comprising the UN security council: the US, UK, France, Russia, and China, before expanding to more countries.

As for which media would be labeled “state-affiliated,” Twitter said these would be outlets where the state exercises control over editorial content. “Unlike independent media, state-affiliated media frequently use their news coverage as a means to advance a political agenda,” Twitter wrote. The company made clear that the “state-affiliated” label would preclude organizations such as the BBC in the UK, and National Public Radio (NPR) in the US, which receives some federal funding but maintains strict editorial independence policies.

As the labelling process was implemented, in consultation with independent experts on the Twitter Trust and Safety Council, certain individual employees at Chinese state media also received this label. Prominent among them was Hu Xijin (胡锡进), the Global Times editor-in-chief known for his outspokenness on social media, both inside and outside China. Hu seemed to notice soon after the new policy that Twitter users were less interested in what he had to say. On August 14, 2020, a week after his Twitter account was labelled, he tweeted that he no longer saw the same level of growth in new followers that he was used to – and he had noticed people unfollowing him. “It seems Twitter will eventually choke my account,” he wrote.

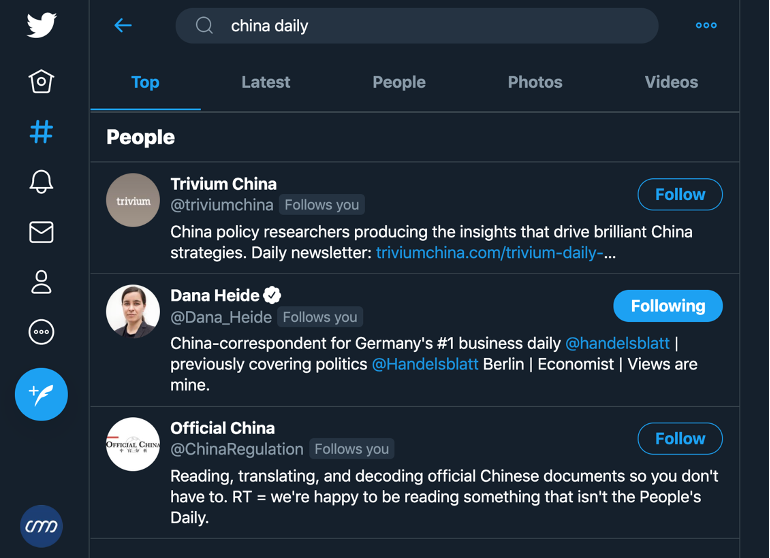

As it applied the new label, Twitter also said it would no longer amplify or recommend state-affiliated media accounts or their tweets. This means that Twitter accounts like that of China Daily, the state-run English newspaper, no longer feature at the top of search results when users search the service with keywords like “china daily,” which amounts to unpaid promotion of such accounts. This followed a 2019 policy by which the company restricted the purchase of advertising by “state-controlled news media entities.”

For many businesses, advertising services on Twitter, through tools like “Quick Promote,” are an important way to boost engagement, increasing followers and website traffic. But Chinese state media and diplomats have also seen platforms like Twitter and Facebook as essential channels in getting global audiences to hear official state narratives, and redress what China’s propaganda officials regard as a serious deficit in what they call “international discourse power” (国际话语权), and what they regard as a key aspect of China’s “comprehensive national power” (综合国力).

Borrowed Boats

China is broadly seen by CCP leaders as lacking in “soft power,” a concept introduced to international relations theory in the 1980s by American political scientist Joseph Nye, and which in 2007 was incorporated into China’s political report to the 17th National Congress of the CCP through the phrase “cultural soft power” (文化软实力). Leaders essentially see the country’s lack of soft power, or its “discourse deficit” (话语赤字), particularly against the strength of Western media and governments, as having a serious impact on China’s international ambitions.

While China’s government has tried to address this “discourse deficit” by pouring huge resources into the international development of state media, and into a broad campaign of public diplomacy, its cultural and media products have had limited appeal abroad. Looking to bolster his country’s image, and to balance against international criticism, president Xi Jinping urged state media in 2013, during an August meeting of propaganda ministers from across the country, to “tell China’s story well” (讲好中国故事). This catchier propaganda notion has now essentially supplanted talk of soft power, to become the central catchphrase encompassing a modernized notion of what the CCP has long called “external propaganda” (外宣). In fact, Xi spoke in his 2013 address of “innovating external propaganda methods . . . that integrate the Chinese and the foreign.”

But despite China’s massive external media investments, reaching foreign audiences has been difficult, and so these same outlets rely on Western social media to share China’s viewpoints. They have been aggressive in making sure they have a big audiences – or at least appear to have them – on major platforms like Twitter. Some Chinese state media have spent millions of yuan to expand their base of followers on both Twitter as well as Facebook, as tender documents show. A government notice published in August 2019 showed that China’s top internet control body, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), had a one-year agreement with the People’s Daily for the latter to promote information about China on Facebook for 5.8 million yuan, or just over 800,000 US dollars. State media have also been suspected of buying followers on social media networks.

China’s use of Twitter has long been viewed as problematic, particularly given the banning of Western social media platforms inside China, and restrictions on the use of domestic Chinese platforms by Western news outlets and foreign diplomatic missions. State outlets like China Daily, which joined Twitter in November 2009, just five months after the network was banned in China following riots in the northwestern city of Urumqi, have been given relatively free reign to espouse Beijing’s viewpoints on Twitter, Facebook, and other services outside China. Western news outlets and foreign diplomatic missions in China operating accounts on Chinese domestic social media platforms such as Weibo, a popular microblogging service launched in the wake of the Twitter crackdown, have frequently been censored or blocked outright.

China has also been accused of abusing its official presence on these platforms. In August 2019, Twitter said it had “reliable evidence to support that . . . . a coordinated state-backed operation” was pushing out misinformation regarding protests in Hong Kong, and suspended some 200,000 accounts. Subsequent actions announced in September 2019 and June 2020 removed thousands of other accounts.

In 2020, accounts run by Chinese media or government actors actively promoted conspiracy theories on the origin of the virus that causes COVID-19. ProPublica in March reported on more than 10,000 fake or hijacked accounts that promoted Chinese government viewpoints. Meanwhile, Chinese nationals who use VPNs or other tools to jump the firewall and tweet messages going against the government’s viewpoints can face prosecution by the authorities.

With Beijing seeming more assertive than ever in its effort to change how its actions are viewed in other countries, Twitter isn’t the only company that has increased its scrutiny of Chinese media. A number of newspapers around the world that previously carried paid inserts from state propaganda outlets like China Daily, another favored way of utilizing Western channels to reach broader audiences, have recently stopped the practice. They include the New York Times, the Washington Post, The Telegraph, and several Australian media. Newspaper inserts are just one of many “borrowed boat” methods that China has employed in an effort to get its message out to audiences in the West and elsewhere in the world.

Splitting Differences

Our research suggests that Twitter’s new labelling policy has to some extent curtailed the ability for Chinese state media to reach audiences outside China. But Twitter’s move has also elicited criticism for painting all Chinese media with the same brush. Long-time readers of CMP, which has tracked Chinese media development since 2004, will be aware that the media landscape in China has changed dramatically since the 1990s, with the emergence before the new millennium of a new generation of more market-oriented media. In many cases, media affiliated with the Party-state, such as commercial spin-offs of Party-run publications at the provincial and city levels, pursued a more daring brand of professional journalism against the formal constraints of the media control system.

Through the 2000s, these media often challenged official narratives with strong reporting from the scene of breaking news stories, such as the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, or through in-depth or investigative reporting. And while Chinese media have faced a far more difficult professional environment since 2012, owing to more determined political controls and a digital transformation that has fundamentally changed the commercial environment, it should be recognized that there are still marked differences between media outlets – and not all are simply propaganda organs.

Fang Kecheng, a former journalist and now assistant professor of journalism and communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, says that, in principle, it is not a bad thing to help social media users better understand the content they are viewing. But Twitter’s current label, while not strictly inaccurate, lacks important context. “There is simply no private newspaper or TV station in China,” he says. “But media outlets like Caixin are significantly different from Party mouthpieces like the People’s Daily.”

A prime example of the complex phenomenon of journalism undertaken within constraints, and with state affiliation, Caixin was launched in 2010 by Hu Shuli (胡舒立), a respected journalism veteran who for many years ran Caijing magazine, a commercial business publication that distinguished itself into the 2000s with heavy-hitting investigative stories, such as its series on the 2003 SARS epidemic. Hu remains Caixin’s publisher, and has a strong team of journalists that continue to pursue tough stories in a difficult environment. In March 2020, for example, the outlet called into question the official Covid-19 death toll figures being released in the city of Wuhan. In 2016, Caixin even spoke out directly against the CAC after it ordered the deletion of a critical article. Such open criticism of official censorship is rare in China.

Caixin is a commercially operating media outlet. Like all media in China, however, it must have some affiliation with the state through a so-called “sponsoring institution,” or zhuguan danwei (主管单位), responsible for maintaining the CCP’s ultimate control over the press system. The sponsoring institution” overseeing Caixin is the Chinese Literature and History Press (中国文史出版社), a publishing house operated by the General Office of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), a political advisory body.

It is important to recognize that media like Caixin, while also state-affiliated, can have room for critical and investigative journalism, Fang says. He suggests Twitter could refer users to a third-party website with detailed information. It might be possible, he says, for social media companies to commission such a site. At present, there are no reliable expert sources for a more detailed understanding of how various media operate. YouTube, which began labeling “news broadcasters that receive some level of government or public funding” in 2018, links users to Wikipedia.

In a written response to CMP, Twitter said it defines state-affiliated media as “entities that are financed and/or editorially controlled by a state or government authorities. This control can be exerted through self-censorship or direct publication of information per the directive of the government.” The statement continues, “We think it is important for people on Twitter to know when they’re seeing media of this nature so that they can draw their own conclusions.”

The conclusions many users are drawing, our analysis suggests, are leading them to disengage with Chinese media across the board. Just a handful of labeled accounts received more attention from Twitter users after labels were applied.

Tweets from China Xinhua Sci-Tech, which shares “science, space, health and environment news from Xinhua News Agency,” received more likes but also fewer retweets. Tweets by Sixth Tone, an English-language online magazine under the state-owned Shanghai United Media Group that like Caixin can sometimes go out on a limb in covering more in-depth stories, were liked 6 percent more but also retweeted a third less. Party newspaper Guangming Daily was a rare Chinese news outlet to — barely — improve in both categories.

Some accounts labeled “China state-affiliated media” can still pay to promote their tweets because they fall under the exception for outlets focusing on entertainment, travel, or sports. According to Twitter’s Ads Transparency Center, XinhuaTravel, Xinhua’s XHSports, as well as PDChinaLife, PDChinaSports, and ChinaScience, three accounts run by People’s Daily, are all still able to promote tweets. Possibly as a result, some of these accounts saw relatively big changes — both positive and negative — in the number of likes and retweets.

Though these accounts do not engage in the most overt kind of propaganda, their tweets still occasionally espouse Chinese government standpoints, such as that Taiwan is unequivocally part of China, or promote propaganda projects such as the China International Import Expo or the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao bridge. They also tweet about China’s COVID-19 diplomacy and spread alternate versions of where the virus may have originated. Twitter’s state media ads policy states that, “If the content is mixed with news, any advertisements will be prohibited.” But, according to the company, the above-mentioned accounts are not in violation.

Another outlier was the Twitter account of iPanda, a product of state broadcaster CCTV which almost exclusively shares cute photos and videos of giant pandas. Both likes and retweets were up by more than 50 percent. Twitter confirmed that the account is allowed to advertise, but that it hasn’t since at least August 6.

The takeaway, it seems, is that China’s most reliable soft power trump card is the adorable antics of its bamboo-munching black-and-white bears.

NOTE ON METHODOLOGY:

We looked at Twitter accounts belonging to media companies that are labeled “China state-affiliated media” by Twitter and have more than 50,000 followers. Because Twitter declined to give a full overview of such accounts, our list (attached below) might not be complete. The only deliberate exclusion from our sample was @XHIndonesia, a local Xinhua account, which, despite some 65,300 followers, did not receive enough engagement.

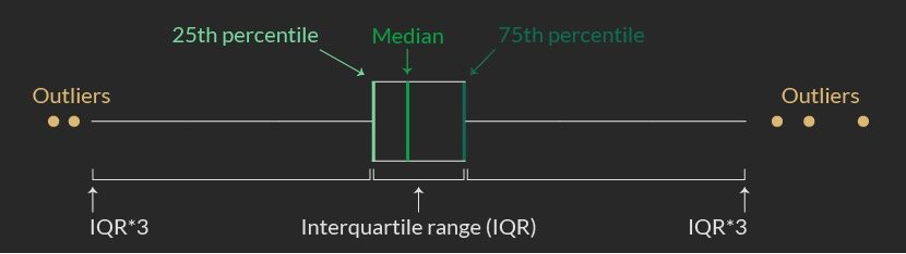

We scraped the numbers of likes and retweets of all Tweets by these accounts, between June 17, 2020 and September 25, 2020. Using August 6, 2020, as a breakpoint, the average engagement performance of Tweets before that is seen as a baseline. To rule out potential influence of outliers (e.g. Tweets receiving unusually high engagement), these were taken out when calculating the average engagement metrics.

Our analysis does not necessarily prove causality. The drop in shares and likes could also have other causes — for example, because fewer news events that happened in China following the labeling managed to grab readers’ attention. It also does not take into account any changes in follower numbers over the surveyed period, or differentiate between the effects of Twitter’s various policy changes. Not all engagement might be organic.

LIST OF ACCOUNTS:

@caixin

@CCTV

@cgtnafrica

@cgtnamerica

@cgtnarabic

@cgtnenespanol

@CGTNOfficial

@cgtnrussian

@ChinaDaily

@chinaorgcn

@ChinaPlusNews

@ChinaScience

@Echinanews

@globaltimesnews

@Guangming_Daily

@ipandacom

@PDChina

@PDChinaBusiness

@PDChinaLife

@PDChinaSports

@PDChinese

@PuebloEnLnea

@shanghaidaily

@SixthTone

@thouse_opinions

@XHespanol

@XHJapanese

@XHNews

@XHscitech

@XHSports

@XinhuaChinese

@XinhuaTravel

@yicaichina

Kevin Schoenmakers