A Murder to ensure a proper burial

On April 7, Jizhou Studio (极昼工作室), a narrative non-fiction account at Sohu News, published a story called “The Man In Search of a Corpse” (寻找尸体的人). Written by Li Xiaofang (李晓芳) and Chen Kaiyue (陈锴跃), the story gave a chilling account, based on police records released in January, of the murder on March 1, 2017, of Lin Shaoren (林少仁), who was forcibly inebriated and then nailed inside a coffin.

The absurd cultural roots of the crime, and the possible involvement of local officials, made the story an instant hit on WeChat and other social media platforms, and the original post was quickly removed – though it remains at a number of locations, including The Paper (and archived at CDT). The gist of the story is that in order to skirt around local laws since 2012 in the city of Shanwei (汕尾市) mandating cremations and prohibiting burials, one wealthy local family paid a huge sum to secure a corpse that could be cremated in the place of a deceased family member, Old Huang, who had died of lung cancer. The deadly scam allowed the Huang family to retain Old Huang’s corpse for internment in the family burial plot. The unfortunate choice for the corpse was the very much alive Lin Shaoren, an intellectually disabled man dear to his family who spent his days collecting plastic bottles and idling outside a local convenience store.

One of the men possibly involved in the scam, which perhaps points to a local black market in corpses to circumvent cremation regulations in a region where ancestral rites are still taken very seriously, was the former deputy director of the Party and Government Office in Guangdong’s Hudong Township, who had also been in charge of the local funeral register.

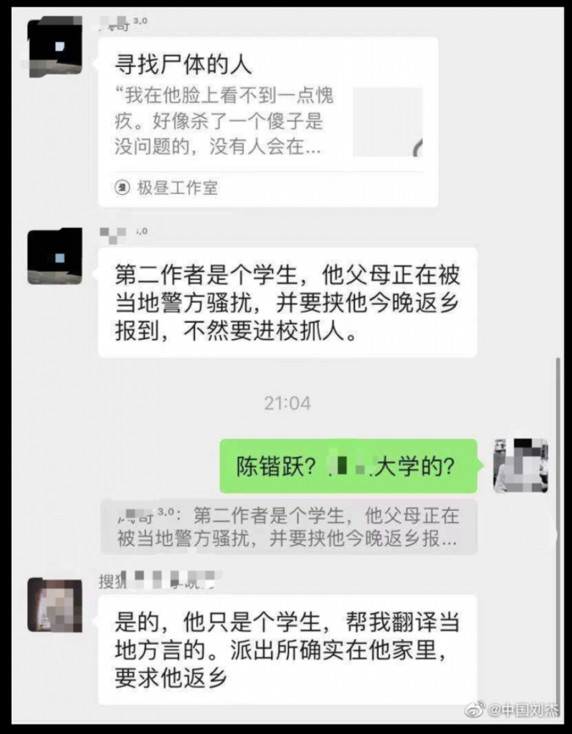

On April 8, the day after the story was published, there was a flurry of discussion in chatrooms on WeChat as Li Xiaofang, the chief author, reported urgently that the parents of her co-author, Chen Kaiyue – a university student from the Shanwei area who had helped conduct interviews in the local dialect – were being harassed by local police and other officials demanding their son return to face investigation.

It soon emerged that Chen Kaiyue is a current student in the journalism program at Guangdong’s Shantou University. According to the discussion online, Chen had been urged by local authorities in Shanwei to return home immediately and face investigation, otherwise the police would “enter the university and arrest him.”

Hong Kong’s Apple Daily reported that Chen’s classmates had appealed for help, saying that police officers from Jieshi Township, which is under the jurisdiction of Shanwei, had paid a visit to Chen’s parents to “verify the situation,” and that the local Party secretary had phoned Chen urging him to “write a document in order to eliminate the negative impact of the incident.” This likely refers to a demand that Chen essentially sign a formal statement with wording provided by authorities, retracting the story and admitting guilt for having disturbed social order through its publication.

In the comments section below a post to Weibo by journalist and former CMP fellow Tang Jianguang (唐建光), readers expressed the hope that the young journalism student could be protected from retaliation by local officials. “I hope the internet can protect this young person who has not done anything wrong,” said one user. “In the way they avoid pursuing the root causes and instead deal with the people who uncovered the problem,” another wrote, “one can suppose the worst possible motives here. How many of them were buyers themselves in this racket and hidden [from responsibility]? How powerful is crony capitalism!”

The original story is well worth a read, an interesting look at some of the stronger journalism and non-fiction writing being pursued in China despite much tighter controls on reporting in recent years under Xi Jinping. We offer an inferior, excerpted translation below.

The story’s arguable shortcomings should be acknowledged as well. For example, it is only much further down in the piece that Lin Shaoren, the victim, is actually identified by name (real names are used only for Lin and his brother). Instead, the murdered man is called repeatedly “the fool son of the Lin family” (林家的傻儿子), or just “the fool son.” The constant reference to “the fool” is painful to read, and the insensitivity to those with intellectual disabilities rattles in translation. It is noteworthy that in reporting on the censoring of the Jizhou Studio story, Hong Kong’s Apple Daily referred instead to the murder of an “intellectually disabled man” (智障男子), better according with professional consensus on how to refer to people with disabilities. In the excerpt below, we have taken liberties with the translation of these unfortunate references to “the fool son.”

The Man Who Sought a Corpse

Everyone in the village knew that the intellectually disabled son of the Lin family had disappeared. For two and a half years, no one could say whether he was dead or alive. The Lin family had reported his disappearance to police, and the whole department had gone out searching for months, though fruitlessly.

The day after the disappearance, the owner of the small convenience store at the entrance to the village had gone over to ask the Lin brothers: “Where has that one in your family gone?” The son had been mild-mannered. And though mentally not too bright, he had gotten on well with people. Often, intellectually disabled people from their village and other villages around had gathered outside the village entrance, out in front of the convenience store. At their most lively, there might be three or four of them crouching in a row, their eyes casting about, and no one knew what they were thinking.

The Lin family imagined all sorts of worst-case scenarios. Lin Zailong (林再龙), 28, the family’s youngest son, said: “I wondered whether my second brother might have walked out that night and accidentally fallen into the pond.” Rumors spread around the countryside that some elderly and homeless people who wandered about and seemed to have no one to rely on were sometimes carted off and their organs sold. After Lin Zailong heard this, he worried that perhaps this fate was what had befallen his brother as well.

The Lin family’s disabled son was born in 1981, the second of six brothers. When he was just six months old, his mother, Chen Xiangmei (陈香妹), noticed that the child was a bit different, his expression blank. When he was old enough to speak, he seemed unable to speak a word, and when adults spoke he couldn’t understand. Chen Xiangmei felt in her heart that the child’s mind might be defective, that he was a fool.

If he’s a fool, Chen Xiangmei thought, then he’s a fool. So long as he learns to say ‘eat’ when he’s hungry. Her second son grew well to his 30th birthday, with a fleshy round face, small eyes, his height just under 1.6 meters, his body strong. He was almost never sick. She taught him on her own from childhood, though still his speech was speech was obscure and others could not understand. But he could express himself over the simple demands of life — eating, bathing, sleeping. And he could get on with life. He remembered his own name, and their home address. For Chen Xiangmei this was enough.

68 years old now, the whites of Chen’s eyes are clouded as with a layer of fog. Speaking of her disabled son, raised with such great difficulty, she can’t stop crying. “When I think of him, it’s like a knife is twisting into my heart.”

On the day of his disappearance, her son woke around noon. He said he planned to go out after lunch to collect plastic bottles, which he exchanged for money to buy cigarettes and snacks. All his life he had lived in the town of Jinxiang, in Guangdong’s Lufeng City. He was familiar with the roads crisscrossing several villages in the town. He would go out every day to collect scrap and watch games. He would generally return home at night without incident.

That day, he had put on a military cap patterned with desert camouflage and gone out, stopping first at his brother Lin Zailong’s house. Lin Zailong had just gotten married that year, and he had new baby. He enjoyed his white and tender little nephew, and from time to time he would go over to have a peak, cooing and playing with the baby, laughing happily. After sitting for a while, he picked up his woven snakeskin bag and said he was going out to collect bottles. That was the last memory his brother had of him.

Six o’clock that evening, Chen Xiangmei felt a bit panicked. Her disabled son had not yet come home. Usually, as mealtime approached, he would arrive home just before. She called over to her youngest son, Lin Zailong: “Your brother hasn’t come home since one o’clock.” Lin Zailong reassured her. Surely, he would come back later.

A mother always seems able to sense when things are wrong. That night, Chen Xiangmei was unable to sleep. She lay awake in bed, tossing and turning. It was midnight, and still she did not hear the familiar voice calling out from the door, sticky as though with a mouthful of sugar. Chen Xiangmei got up and called her third son. The third son, who was off working in Wukan, answered her cal and drove back to Lufeng overnight. At dawn, the family went out searching through several villages in Jinxiang. But there was no trace, like a raindrop lost in the sea.

The Lin family’s disabled son had disappeared in March 2017. It was another two and a half years before the family received a call, in November 2019, from the town’s police station. Only then did they learn that he had died on the day he had disappeared. A criminal ruling made public in early January this year [2021] on the website China Judicial Documents (中国裁判文书网), describes in detail what happened on that day.

_______

After leaving Lin Zailong’s rented house, the Lin’s disabled son walked another two or three hundred meters and turned onto the village’s main road, a busy village road always bustling with traffic. There are two public garbage bins on the side of the road. As the Lin’s disabled son was bending over to fish out plastic bottles from the garbage cans, a white van pulled up beside him. A chubby middle-aged man got out of the car and exchanged a few words with him. Then, determining that he was intellectually disabled, the man pushed and shoved him into the van and drove away from Jinxiang.

On the way, the middle-aged man bought six bottles of red rice wine, more than 30 proof, and made sure the Lin’s disabled son drank them all. Then, he stuffed him into a coffin he had prepared in advance and sealed it up with nails, killing him.

The reason for this killing was absurd. A local man in his 50s had died, and had asked before his death that he not be cremated. Instead, he wanted to be buried. Someone was willing to pay the money, and someone was willing to help make it happen. And so, the Lin family’s disabled son became the substitute. He was killed and sent to the funeral home as a substitute for the crematorium.

. . . . .

[The article follows with a section on Chen Fengbin (陈丰斌), the local man who was later found to have kidnapped the Lin’s son.]

According to a criminal ruling released in early January 2021, Chen Fengbin’s work after the crash included transporting caskets for people. He met an older brother surnamed Wen, who often helped the funeral home by driving bodies or delivering people to the funeral home. When he was too busy, Wen would ask Chen Fengbin to help, the cost of transporting a casket is 200 yuan.

[Later section on the family wishing to have a burial and avoid cremation]

In February 2017, Old Huang, a resident of Lufeng’s Hudong Township, was suffering from advanced lung cancer. On his deathbed, he voiced his last wish to his brother Huang Qingbai (黄庆柏): That he not be cremated. As early as 2012, the city of Shanwei under which Lufeng belongs began implementing an “All In One Stroke” (一刀切) policy banning burials and the sale of burial coffins. Huang Qingbai approached a friend and asked if there was any way for him to realize the last wish of his beloved brother? The friend gave him the phone number of someone working at a funeral home.Huang Qingbai reached the funeral home contact, Liang Chenglong (梁成龙), then 58 years old, who was the former deputy director of the Hudong Township Party and Government Office as well as the funeral registrar. In a later confession, Liang Chenglong claimed that Huang Qingbai wanted the phone number of the funeral home driver, so he provided Huang with the contact information for Old Wen, and claimed he did not know about the Huang family’s transfer of the body to avoid cremation. However, it is noted in the transfer for examination and prosecution from the Lufeng City Public Security Bureau that: Liang Chenglong agreed the matter of the body transfer with Lao Wen, and asked that received 10,000 yuan once the matter was resolved.