The Power of Empathy

Fang Kecheng

Kou Aizhe

From Hobby to Team Effort

Fang Kecheng: Hello, Aizhe. Actually, I was a very early listener to this podcast of yours. In the beginning it was actually called “Aizhe Radio,” isn’t that right?

Kou Aizhe: That’s right. That was in 2016. You might say that the earliest podcasters were narcissists who liked attaching their own names to their shows.

Fang Kecheng: You were still an assistant for the foreign media at the time?

Kou Aizhe: I was an assistant in the Beijing Bureau of Swedish National Radio, working there for four years. In 2014, I job-hopped to CTV, Canada’s largest private television network, where I was again in the Beijing bureau. There was a period of time when their correspondent in China had resigned and nothing was happening in the office. So it was boredom that really started me doing this podcast.

I’ve always been a fan of podcasts, and I mostly listened to storytelling podcasts from North American or the UK. I kept expecting Chinese to do similar types of storytelling, but no one was doing it, so I decided to try it for myself during this gap period. I made seven episodes.

Fang Kecheng: So after seven episodes Elephant Magazine picked you up?

Ko Aizhe: Yeah. There was this one time I went to their office at Elephant Magazine and introduced my podcast to Huang Zhangjin. He got really excited. He knew a real mix of people, all sorts of people with different stories. He realized that a program like this was probably the best way to get these individual stories out. At the time he was incubating all kinds of programs. So he invited me, saying right out: “Come over to Elephant.”

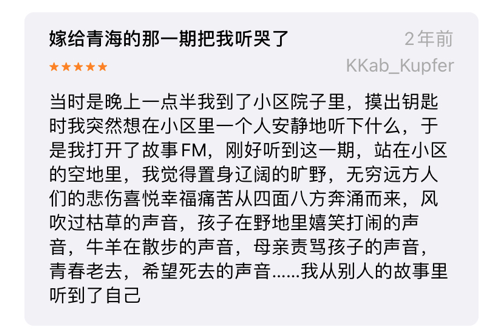

Praise on social media for Gushi FM: “I came to the courtyard of my apartment compound one night, and as I was searching for my keys I suddenly saw someone from the compound sitting quietly and listening to something. I opened up Gushi FM and listened to one episode, standing there in the courtyard, and I felt the sorrows and joys of people out there in the vast wilderness . . . “

Because I had done seven shows already, and the podcast was pretty well developed, the format was kept once I went over to Elephant Magazine. After that I started to recruit people – producers, post-production, operations. With eight people including myself we refined our work process little by little.

In foreign countries podcasts like ours are generally released weekly, so at the beginning I also was weekly releases. But Huang Zhangjin at Elephant suggested we increase the frequency, because China didn’t have programs like ours, and people weren’t that familiar with it. So we went to three episodes a week. In the podcasting world you could definitely consider us model workers.

Approaches to Storytelling

Fang Kecheng: Since you mentioned the show’s format, I seem to remember that Aizhe Radio was a bit different from Gushi FM. Perhaps it was because the longer production cycle of Aizhe Radio allowed for more delicacy in the treatment, and the sound elements that could be used for storytelling were richer.

Kou Aizhe: Actually, there are so many different ways of storytelling. It’s just that when I was Aizhe Radio, my thinking was to do more audio documentary, and to sounds of ongoing stories on-the-scene, for example. Definitely the production cycle was longer. And in fact during the early days of Gushi FM this was true too, because we were weekly, and each episode took a long time to polish. So things were a bit more refined. When I started Gushi FM, the slogan I wrote was: “Gushi FM is a podcast that tells real stories. I’m Aizhe, a collector of stories. Here I will use the audio documentary form to take you across the paddy fields and through the hutongs to gather these touchingly true stories.”

These days the program is roughly divided into two types of shows. One is the personal storytelling type (个人口述类), which is the majority of our program format. The other is the audio documentary (声音纪录片). In fact, we are doing both. But the production costs of audio documentary are really high, and it usually takes anywhere from three weeks to a month to produce a single episode. If we want to do three episodes a week, we can’t possibly produce an audio documentary every day. We can only intersperse them.

Our next step is to quickly expand our team. We can definitely do a lot more with the proper team. Aside from audio documentary, we’ve experimented with a lot of different formats. For example, we’ve also done “interviews with regular people” (素人采访), in which we direct some of our listeners in interviewing their own parents or grandparents.

Fang Kecheng: You mentioned that you enjoy listening to storytelling podcasts from North America and the UK. What have you taken away from these shows in the production of Gushi FM?

Kou Aizhe: Yeah, we’ve learned a lot, especially from programs like This American Life and Snap Judgement. We’ve taken a lot of cues from them. Then we placed an emphasis on personal storytelling, which perhaps more references China’s own conditions in terms of consumer habits and market development. This definitely brings the cost down, and gives maximum results.

Actually, from market angle, some of our more intently produced audio documentaries have drawn less interest perhaps than our personal storytelling episodes. I think what our audience values most is that the details of personal expression are particularly rich and moving. Beyond that, they actually don’t care a great deal about production value.

Fang Kecheng: How do you make sure the expression of someone you interview is rich and full of detail? Is that just a matter of their natural gifts?

Kou Aizhe: It definitely can’t rely on natural gifts, otherwise there would be no way to standardize it. A lot of audience members also ask us how we manage to find so many people who have this amazing way of expressing themselves. It’s actually a big misunderstanding. The impact of their voices depends on our team, how topics are chosen, how we select interviewees, how we conduct the interviews . . . . These things are most critical.

For example, my personal preference is not to rely too much on pre-interviews. I just need to have a rough idea of what the story is about. When the person comes in, I get them into conversation mode as I might with a friend. I don’t use the word “interview.” I’ll say, you’re in a conversation with a friend, and you can speak freely and know we’ll do our utmost to keep you safe. We can make conversations anonymous too, allowing them to be spontaneous.

The most difficult interviews have been with people who were slightly older, or slightly less educated. You need to ask them about all sorts of details, digging out the nuances of the story little by little.

Fang Kecheng: I suppose a lot of these interviewing skills come from your previous media experience.

Kou Aizhe: Yes. In fact, I think it’s quite a coincidence. Whether it’s my previous work experience or my personal hobby of watching movies, it all comes into this work, naturally and logically.

Fang Kecheng: You just said something about when people come in. Does this mean that all of your interviews are done in the recording room?

Kou Aizhe: In the past that happened most of the time, because face-to-face conversations really work best. Since the epidemic, a lot of interviews have moved online, but that means more uncontrollable factors, like poor recording quality, or interviewees that don’t feel relaxed.

Fang Kecheng: You just talked about product standardization. Internally, do you guys have a manual or something like that? Or is this all just in every staff member’s head?

Kou Aizhe: Normally, I will do a simple training for people who are just starting out. Once the training is done, it’s really about trial and error, because we’ll have an audition for each program, and then everyone sits together making suggestions and airing criticisms. Over time you get a clearer idea of what works, what doesn’t, and what you’re missing. These are all pitfalls you have to deal with as they come.

Since the epidemic, a lot of interviews have moved online, but that means more uncontrollable factors, like poor recording quality, or interviewees that don’t feel relaxed.

Fang Kecheng: Could you walk through the specific production process for each episode?

Kou Aizhe: We still work like a traditional media newsroom. Every Monday we have a pitch session. People will make their pitches to me, and then I’ll make approximate judgements about what will work and what won’t. If an idea gets the green light, we start looking for interviewees. I may have more resources on my side, so if people can’t locate the right source I’ll help put them in contact and we’ll arrange interviews. Then the producer steps in.

In fact, the producer is the core of the program. They conduct the interview, make a rough cut, and the team will listen to it together, and everyone will grade it and make comments. In the end, it has to be my decision whether to release it or not, in the interest of ensuring the quality of the program is consistent. If it makes the grade, it’s then handed on to the post-production team to do the fine editing, adding the soundtrack. After that it’s released. That’s roughly the process.

Fang Kecheng: What percentage of the programs are rejected after the team session?

Kou Aifang: It’s not a very consistent thing. Sometimes it can be very high, and sometimes very low. In deciding on topics, actually, I’m pretty loose. I still hope everyone can explore programs and topics we haven’t done before. But if everyone on the team feels after the final production that a program just isn’t working, I definitely won’t release it online.

Fang Kecheng: So I guess there is bound to be a certain level of scrap.

Kou Aizhe: Yeah, for sure there’s going to be scrap. But I think the process is totally worth it. It’s definitely worth exploring more ways to tell stories.

Fang Kecheng: When you make initial judgements about programs, do you think it’s more a matter of your professional judgment, or are you thinking more about the preferences of the audience? Based on the data you’ve collected over the hundreds of episodes you’ve done, I suppose you can pretty much tell what kind of stories your audience likes.

Kou Aizhe: It’s definitely a balance. Now that I’m more mature in my expectations of the audience, I don’t really think about the audience that much. I always say to the team, you don’t have to anticipate the audience, because we’re all going to sit together and listen, and it’s enough if you can please the whole team. If the team accepts it, it’s a good episode. If our team isn’t pleased with it, it won’t be released.

In fact, in its current format Gushi FM doesn’t have a particular threshold. What I mean is, audiences can listen to it no matter what their level of education is, and regardless of whether they come from a first-tier city, or from small-town and rural markets. But everyone’s going to be different in terms of how they understand a program. So you can’t please everyone. Rather than analyze the market, we just need to look at the opinions within our team.

Fang Kecheng: Based on the data you’ve seen behind your programming, what sort of shows do people prefer?

Kou Aizhe: There are two main directions. The first is the bizarre experience program. The other is the program with strong resonance for people (强共鸣类). In the bizarre experience category, you have stories like someone going to jail in Syria, or someone going to Pakistan to get a wife, or someone serving on a jury in the United States. These are things you don’t ordinarily experience in your life.

As for strong resonance stories, a while back we ran a program in which the mother of a baby complained about the hardships of raising children. Or a program about having a girlfriend who suffers from depression. They can be very common stories that all of us, or those close to us, have experienced. They’re not strange at all, but as you listen to it you feel that it resonates with you.

Fang Kecheng: Do you have your own favorite episode or episodes of the show?

Kou Aizhe: That’s a really hard choice to make. I like most of the shows – otherwise, I wouldn’t have put them on. But in terms of topic selection and interview approaches, I can offer one example. In 2007, there were these two brothers who were buried in a collapse at a small coal mine in Fangshan District outside Beijing. The rescue team came and tried to rescue them for a while. But then the team decided it was pointless, because they must have died. So they left. About a week later, the brothers managed to dig a hole by themselves and crawl out. Again, this was a story from 2007. I’d been thinking about it for a long time, feeling it was perfect for a film.

In 2017, after a bit of research, I tracked down one of the parties involved. So [that year], ten years after the incident, I went to a construction site in Changchun and found him. He was working as a construction worker. So I went back over the whole story again. But you know migrant workers aren’t so well educated, so it was really difficult interview. I had to squeeze out one sentence after another, but the end result was really good.

In fact, I think the golden age of journalism in China was full of really great stories. They may be too old now for journalism, but as stories they are really great, and they’re worth revisiting all these years later.

First the Story, Then the Opinions

Fang Kecheng: What do you think Gushi FM ultimately points to? Or, what is the concern behind it? What do you hope to accomplish by telling these stories?

Kou Aizhe: The result I hoped it could achieve I think it’s achieved already. If you look at the comments from our audience, you see that everyone is pretty unanimous [on the show’s success]. They often say that after listening to our program, they feel they’ve experienced many different paths in life. And that a lot of things they might have thought before were just curiosities are actually ordinary choices people make.

In fact, I think the golden age of journalism in China was full of really great stories. They may be too old now for journalism, but as stories they are really great, and they’re worth revisiting all these years later.

I often say Gushi FM is a podcast about understanding. Because one of the best things storytelling – and especially audio storytelling – is really great at doing is to get people to relate. When you put yourself in another person’s shoes, when you view things from another person’s point of view, and when you think about their situation and their choices, it’s much easier to understand and relate to them. So I think it would be really helpful for people from different camps to have a chance to sit down and listen to one another’s experiences, to understand things from their perspective. Not just from a political point of view, but from the point of view of a really good story. So I think that’s the most meaningful thing.

Fang Kecheng: To reach a point of empathy.

Kou Aizhe: Yeah, you could put it that way.

Fang Kecheng: Over the years, it seems we’ve increasingly seen the disappearance of empathy on social media. People not understanding one another, but rather attacking one another. Do you feel that way?

Kou Aizhe: Of course. I think the reason things are like this in our time is because people are so used to opinions first. If you can first make shows that appeal to people, that don’t dwell on opinions but lead with the facts and focus on the details, the experience, the story – all that before coming to a judgement or a conclusion. I think if you can do that it helps to mend the tear.

Fang Kecheng: Yes, and I think the great thing about you is that you’re not talking about dry facts. You’re talking about things that are “saturated” (湿), things that are warm.

Kou Aizhe: Right. And in that sense I think it’s also in line with the rules of communication on social media.

I think stories are as essential to human beings as air and water. If you work to get people to accept your story as much as possible, then they can come to understand your views and see the reason behind them. I think that’s a bit more valuable.

A Personal Perspective on Public Issues

Fang Kecheng: You mentioned earlier that the more bizarre the story, the more people enjoy hearing it. How do you ensure that a story is true?

Kou Aizhe: This is where you have to get really meticulous. The topics were are selecting right now run in two basic directions. One focusses on public issues. For such programs, you have to confirm all the facts and detail, which means doing research. The other focusses more on personal experiences – for example, stories about their family. You can judge whether they are being truthful by asking follow-up questions, and on the basis of our own experience. Their experiences are very personal, and there may not be other witnesses that make verification by a third party possible. So our own experience is really important.

For example, I went to Weinan, in Shaanxi Province, to interview someone who had worked as a mercenary, and that was a riveting story. In fact, I could confirm that he worked as a mercenary and bodyguard in Africa, that his experiences were authentic, because he had the pictures to prove it. There were videos too, and the details he provided were logically consistent. His subsequent experience, as a drill master in Kokang [in Myanmar, on the border of Yunnan province], I could also confirm because he had posted videos to his WeChat Moments every day, and I could see them too.

But his claim that he had been stationed in the Middle East, and how many people his team had killed and so on, none of that was reliable. Because there are a lot of military enthusiasts who read Elephant Magazine, and I consulted a lot of people to verify that part of his story. The story was wonderful, but in the end I chose not to broadcast it.

Fang Kecheng: So you cut out the part about the Middle East?

Kou Aizhe: The whole episode was never released, because without that part the whole story was not cohesive. We will definitely in the future be doing even more public issue topics, and fact-checking will become even more important.

Fang Kecheng: I saw you recently released an episode on Phoenix Tree Holdings, [the failing real estate company]. What made you decide to do more on public issues?

Kou Aizhe: Actually, there were gaps in the Phoenix Tree episode, for which we didn’t interview the company. Since the episode aired, however, we were contacted by a former Phoenix Tree employee who was willing to speak. Actually, we’re really well positioned to offer personal perspectives on public issues, because we have a lot of resources here, and because our audience enjoys hearing personal perspectives on public issues.

Fang Kecheng: Does your interest in doing public issues have anything to do your original wish to work in journalism?

Kou Aizhe: It certainly had an influence. I’m sure this [intention] influenced everyone who at that time wanted to enter the media profession.

Fang Kecheng: What’s your assessment of the risk involved in what you do?

Kou Aizhe: So far, I think, we are the greatest common denominator, and the personal perspective is relatively safe. In fact, quite a few official government agencies have even reached out to us, hoping to cooperate.

Closing the Professional Gap

Fang Kecheng: You were influenced at Gushi FM by American podcasts and the desire to see similar programs in Chinese. Up to now, though, Chinese podcasts have lagged far behind the US in terms of professionalism. What do you think is the reason for this? Is it because in the United States podcasts are often backed by professional radio stations?

Kou Aizhe: This is actually a huge topic. From a professional point of view, it is true that the traditional radio stations in the American market are very mature, whether in terms of talent or in terms of the market. There is competition across the board.

In China, you don’t find this level of competition, even in the talent pool. I used to wonder if there was talent in traditional radio in China. Then I discovered, no, there really is no one out there we can draw from. So now our team is really young – basically, all of them have just graduated. I recruited them to take them on myself, and as long as everyone has a sense of aesthetic judgement all around it’s fine.

Fang Kecheng: Why do you think things are this way [in China]?

Kou Aizhe: I once spoke to a radio station director who told me that there problem was that “eating well is cheap” (好吃不贵). In other words, radio frequencies are a monopoly, and there aren’t too many costs associated. Advertising revenue is pretty good. So all they need are a couple of anchors chatting, and there’s decent income at low production input. So they don’t bother to expend energy developing new types of programming.

Fang Kecheng: There’s a lack of market competition.

Kou Aizhe: That’s right. I’ve talked to a lot of established podcasts in the United States and they say, well, they had courses in “audio journalism” when they were in journalism school, and then they had all these years of experience working in radio, and then they’re out there in the market hoping their shows will be picked up by all the local radio stations.

But I believe that the future of podcasts in China is definitely going to get better and better, especially looking at the trends we saw in 2020. In the audio segment, the market for music is almost saturated. What else can you listen to? Are book reviews and crosstalk, [traditional Chinese comic dialogues], your only choices?

We’ve had more than one investor approach us this year, and everyone has said they want to invest in this business. Platforms are also planning to get into long-form audio (布局长音频), which is definitely a content area that’s missing. I think the bottleneck at the moment is that the format is too homogenous. If we hear better content on audio programs in the future, this will definitely attract larger audiences, and the market pick up.

I believe that the future of podcasts in China is definitely going to get better and better, especially looking at the trends we saw in 2020.

Fang Kecheng: But will the entry of [larger] platforms also mean bringing in more stuff that is garbage? For example, there are decent things on Toutiao and Douyin, of course. But they are often overwhelmed by garbage content.

Kou Aizhe: I see it the other way around, that if things are too clean, this means there aren’t great prospects for the market. It all becomes homogenous.

My favorite model would definitely be to become something like National Public Radio (NPR), which is so cool. I think it would be best to be absolutely neutral and be able to do so much good content without interference. But in China, that’s just not realistic.

Seeking Commercial Success

Fang Kecheng: How does your audience data look right now?

Kou Aizhe: Right now have about one million subscribers across all platforms, and each episode draws about 800,000 listeners.

Fang Kecheng: That’s a pretty high rate of people who tune in.

Kou Aizhe: Yeah. The biggest advantage of podcasts is their stickiness. Most people who subscribe to podcasts tune in a lot. But of course the volume overall doesn’t compare to video right now.

Fang Kecheng: What is your main [business] model right now?

Kou Aizhe: What we do the most right now is customized advertising – a bit like the advertorials you find on WeChat public accounts, which are more about the brand image. For example, Xiaomi once approached us to offer sponsorship. It was their corporate social responsibility department. We produced a show about a Xiaomi office in Shanghai that hired a bunch of blind people to do data labeling for their AI, to help train the AI. As you know, blind people have limited employment opportunities in China, so it was a good story. Even if it’s for an advertisement, we also want to make sure that it’s a true story, and that it’s interesting. That way our listeners won’t have any objection to us accepting this kind of advertising.

Fang Kecheng: Have you tried paid membership?

Kou Aizhe: Our next direction may be down that road. But my hope is that we can do it later on, once we’ve increased our frequency. We release three episodes per week now, so if we all of a sudden started charging for our shows, our listeners would be pretty upset. But if I could release one additional episode each week, and that episode was paid, I think our audience could accept that.

Fang Kecheng: Has Elephant Magazine managed to profit from incubating your program?

Kou Aizhe: Earning money is still not in the picture, because in fact we’ve not really made an effort up to now to commercialize. We’ve focused on increasing the quantity [of programming], and then will come the commercial part. So it’s not been so urgent.

Fang Kecheng: Finally, I wanted to touch on the whole “We Media” industry. I’ve found that many people involved in “We Media,” including those operating WeChat public accounts, podcasts or video [channels], but especially those within the industry who take content seriously, are former journalists. Have you noticed this phenomenon?

Kou Aizhe: Right. And I think this makes sense, because media people have the resources and the experience to explore these new forms of content, and they’re the ones who find it most accessible. And besides, people who have a background in traditional media still generally maintain their bottom line [in terms of professionalism], and they know what sort of people they want to reach. They’re not just chasing after big numbers and accommodating the market.

Fang Kecheng