The Olympic Rings monument, in front of Japan Olympic Museum. Image by RuinDig available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.

Users of livestreaming services topped 600 million in China in 2020, and live streamers have become a powerful force driving the growth of e-commerce in the country. But live streaming has also prompted concern from internet regulators, who see immense potential for a range of abuses in the fast-growing medium – from the marketing of low-quality and counterfeit goods and concerns over standards of basic decency, to violations of political discipline.

When the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), the country’s chief internet regulatory and control body, issued new regulations on live-streaming back in February this year, concerns over the protection of youth and over data security were topped by language about “enhancing mainstream value leadership” (提升主流价值引领), code for the need for platforms to enforce the values of the CCP. The rules also talked about the need for “positive energy” (正能量) to permeate livestreams and the internet generally – this being a term closely associated with the suppression of criticism of the leadership.

But while enforcing censorship guidelines may sound like a rather straight-forward business, it can actually be a messy process for the authorities and internet companies alike. In some cases, enforcement can backfire, achieving the opposite of the intended effect.

An excellent example of this occurred recently during the opening ceremony of the Tokyo Summer Olympics, for which the Chinese internet giant Tencent has been sublicensed broadcasting rights from the state conglomerate China Media Group. Sublicenses were granted to operators like Tencent and Kuaishou, a leading video platform, in order to help boost access to the Games, allowing Chinese users to view sports content through mobile services like Tencent Sports, Tencent Video, QQ.com, Tencent News, and of course WeChat.

During the Olympic opening ceremony on July 23, however, Tencent Video, which has more than 600 million monthly active users in China, made a major fumble as it sought to abide by censorship guidelines. As the Taiwanese delegation of athletes entered the stadium and was introduced by an anchor as being from “Taiwan” rather than from “Chinese Taipei” – the latter being a condition of the island’s participation in the Games settled back in 1981 with the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to respond to China’s objections on sovereignty grounds – Tencent Video responded by quickly interrupting the live broadcast. The livestreaming app replaced the broadcast of the ceremony with a 20-minute segment discussing Olympic sports.

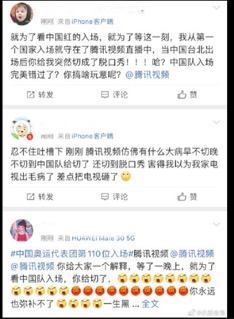

As the talk dragged on, millions of Chinese tuning in to the live stream at Tencent Video were missing an event they had tuned in especially to see: the entry of the 777-strong delegation of athletes from the People’s Republic of China, the largest delegation in Olympic history. Many were furious, as could be seen by the bullet comments streaming across the broadcast. “We want to see the Olympics,” said one frustrated comment. “What are you doing?” another asked. “Cut back!” several demanded.

The disruption by Tencent, a decision taken to anticipate objections from the authorities, drew fierce protests from angered Chinese netizens, who demanded an apology for “selling out our country” at a crucial moment many had eagerly awaited. There were even calls to uninstall the streaming app.

Tencent’s intention, no doubt, was to circumvent a possible violation of propaganda guidelines in their live broadcast. But its inadvertent censorship of the grand entry by China’s own national team immediately rankled with patriotic users, who took to Weibo and other platforms to accuse Tencent of “disrespecting the Motherland,” calling the company “a traitor that deserves to be investigated.”

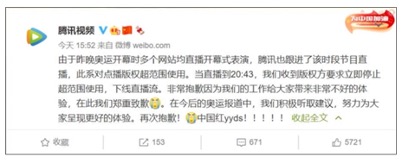

The process behind Tencent’s decision during the live stream of the opening ceremony remains unclear. Was it a technical problem? Or a man-made blunder as the company strove to abide by censorship demands? In an apology posted to Weibo the day after the incident, Tencent attributed the situation to unspecified “demands from the copyright holder.”

Did this refer to the China Media Group, the holder of the broadcast license? Again, it was unclear.

“In Olympics reports from now on,” Tencent Video said, “we will listen to the views of others, and do our utmost to do better.” In the fast-paced and fast-growing livestreaming sector, and with both users and censorship authorities to please, that may prove a difficult promise to keep.