A propaganda from the Cultural Revolution, featuring Mao Zedong at center. Image from SMTH available under CC license.

It is likely that for months if not years to come, observers of Chinese history and current affairs will weigh the significance of an article making the rounds on China’s internet this past Sunday. Appearing on scores of official Party-state media websites and commercial internet portals, the article is penned by a virtually unknown blogger named Li Guangman (李光满), who claims that revolution is in the air in China, with profound transformations to be felt by all.

“This change will wash away all the dust, and the capital market will no longer be a paradise for capitalists to grow rich overnight,” he writes. “The cultural market will no longer be a paradise for effeminate stars, and the press will no longer be a place for the worship of Western culture.” The author’s next line reeks of Maoist nostalgia: “The red has returned, the heroes have returned, and the grit and valor have returned.”

The article opens with a summary of recent moves by the Chinese authorities to bring the entertainment industry in check and curb the influence of celebrities, coming on top of the suspension last year of the blockbuster IPO of China’s Ant Group, the fining of Alibaba, and the crackdown on “fandom culture” (饭圈文化). All of these moves have come amid intensified calls by Xi Jinping, and in the state media, for the country to pursue a renewed form of “common prosperity,” or gongtong fuyu (共同富裕).

Li also mentions recent actions taken directly against music composer Gao Xiaosong (高晓松) and the actress Zhao Wei (赵薇), noting with seeming glee that both have been yanked from major internet portal sites, and that “Zhao Wei’s name has been expunged from the [online video platform] iQiyi.”

The red has returned, the heroes have returned, and the grit and valor has returned.

Li Guangman

Such punitive actions, which have now set the internet and entertainment industries trembling, are apparently what Li means by “grit and valor,” or xuexing (血性), a term that references an attitude of toughness and combativeness that has been actively encouraged within the People’s Liberation Army since 2013. “[All] of this tells us,” Li says, summing up the zeitgeist, “that China is undergoing a major change. From the economic sphere to the financial sphere, from the cultural sphere to the political sphere, a profound transformation is underway – or, one might say, a profound revolution.”

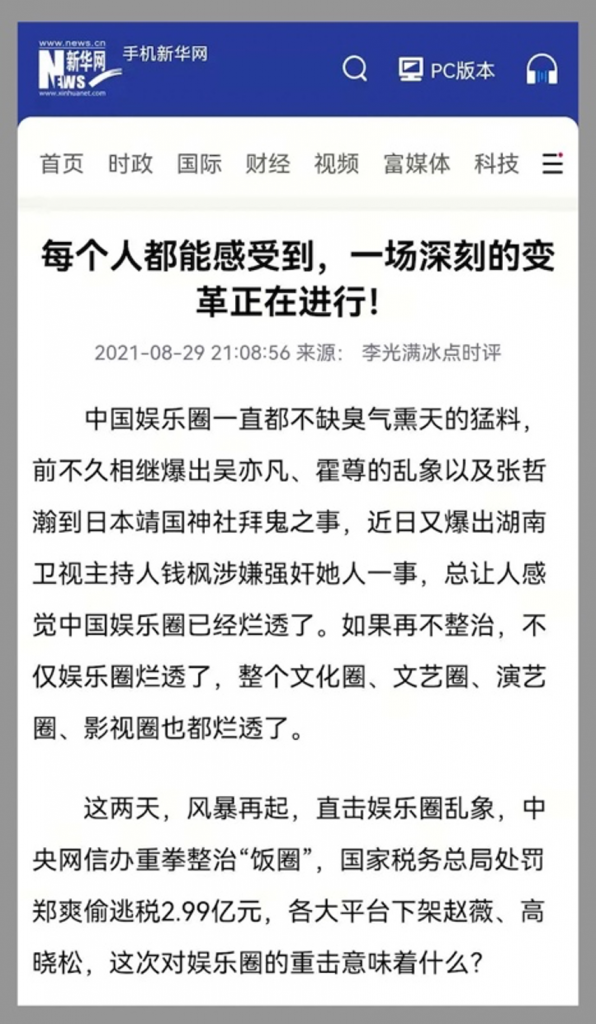

This talk of “revolution” quickly dominated discussion on many chatrooms and social media threads through Monday. Such language, appearing on the odd social media account, might ordinarily be dismissed as the ravings of a Maoist outlier. But this post, though attributed to Li’s own public account, “Li Guangman Freezing Point Commentary” (李光满冰点时评), was shared on the websites of eight major Party-state media on August 29, and on scores of commercial sites, all with the same headline: “Everyone Can Sense That a Profound Change is Underway!” (每个人都能感受到, 一场深刻的变革正在进行!)

The re-publishing by Party-state media of an article from so-called “self-media” or “We media” (自媒体), a term referring to digital social media platforms such as WeChat that integrate self-publishing with chat and other services, is a very rare occurrence. The assumption many observers have naturally made, therefore, is that the joint posting of this WeChat article across Party-state media websites must have been coordinated by the Central Propaganda Department and other relevant offices.

In the social media comment sections this week, the concern has been palpable. “A movement has begun,” one user commented underneath a Weibo post on the Li Guangman article. “They’re blowing a wind to see what fish they can stir up,” said another. A third comment was more portentous: “History is being repeated,” it said.

No one need ask what history we are talking about here. The fear is that the central leadership has effectively green-lit a “Cultural Revolution-style” article, as one user on the Zhihu question-and-answer platform wrote, and that China might be sliding inexorably toward another political movement that would be destructive to the relative openness of the past four decades. Another user on Zhihu wrote of Li Guangman: “This is extreme rhetoric, murderous in tone. To hear him is to return again to that catastrophe of 50 years ago. Any country that wants long-term peace and stability must be moderate internally. And moderation does not mean permissiveness, but rather the resolution of problems in a reasonable and practical manner.”

A New Resolution on History?

In fact, the exact nature of this apparent joint release of the Li Guangman commentary remains a matter of speculation – even for the author himself. On Monday, in the wake of the widespread posting of his article, Li commented on the phenomenon, giving his post the giddy headline: “People’s Daily Online, Xinhua Online, CCTV.com, China Military Online, Guangming Online and Other Central Media As Well as Scores of Provincial, Regional and Municipal Media All Place A ‘Li Guangman Freezing Point Commentary’ Article in a Prominent Position!” (人民网, 新华网, 央视网, 中国军网, 光明网等央媒及数十家省区市媒体集中在重要位置转发”李光满冰点时评”文章!). Li’s apparent surprise and speculation about the attention given to his article suggests he was unaware of any broader propaganda strategy around the piece. “Obviously, this was a unified arrangement by the news and propaganda departments and the Cyberspace Administration of China, generating an extremely strong propaganda outcome,” he wrote.

But is it really so obvious? “It’s hard to imagine,” one media analyst in Beijing said in an exchange over e-mail, “that propaganda departments and the CAC would demand that websites run this piece.”

The fact remains, however, that the Li Guangman article has been widely promoted. There can be little doubt of the article’s importance as a harbinger of something. But of what, exactly? Why would such an article be encouraged and supported at this time?

One possible explanation concerns the possibility that we are about to witness the release of a new “resolution,” or jueyi (决议), on the history of the CCP. Given practices within the Party in the past, such a step would seem necessary if Xi Jinping is serious about defining the current period as a “new era” (新时代), which would go further in making the case for his leadership beyond the 20th National Congress of the CCP in 2022.

A Xi Jinping resolution on history would be the third in a century for the CCP. In 1945, at the 6th Plenary Session of the 7th CCP Central Committee, Mao Zedong issued the “Resolution on Certain Historical Issues of the CCP” (关于党的若干历史问题的决议), the CCP’s first historical resolution, which established and consolidated Mao’s ideology and position. Nearly four decades later, in June 1981, Deng Xiaoping led the passage at the 6th Plenary Session of the 11th CCP Central Committee of the “Resolution on Certain Historical Questions Since the Founding of the Nation” (关于建国以来党的若干历史问题的决议), which established Deng Xiaoping as the “core” of the second leadership generation and defined his opening and reform policies as the direction of the era.

A number of scholars and observers in recent years have predicted the release of just such a resolution. Analyst Gao Xin (高新) wrote in 2018 that Xi Jinping’s release of a third resolution on history was “simply a question of time.” The same year, Deng Yuwen (邓聿文), the Chinese journalist and former Study Times editor, wrote in the New York Times that if Xi wished to “truly open a ‘new era’ belonging to himself,” then “he must carry out a ‘correct’ summarization of the historical experiences of the past 40 years of reform and opening.”

“The current state of affairs is again a delicate one,” Deng wrote at the time, amidst the elevation of Xi Jinping’s banner term. “While the 19th National Congress of the CCP proclaimed a new era, it is not altogether clear what the essential characteristics of this new era are.”

This week, in light of the Li Guangman article, Deng has again suggested that a new resolution from the Party on its history is imminent, and could be unveiled at the 6th Plenum of the 19th Central Committee in November this year. In fact, there may be some clues in the language emerging from yesterday’s Politburo session.

It was pointed out at the meeting that, by learning from history, we can understand [the laws] of rise and decline. Summarizing the major achievements and historical experiences of the Party in its century-long struggle to build a modern socialist nation century of struggle is necessary to persist in the development of socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new era, is necessary to enhancing a political mindset, a macro-mindset, a ‘core’ mindset, and a mindset of compliance, to maintaining confidence in the path, confidence in [the Party’s] theories, confidence in the system, confidence in our culture, and to firmly maintaining General Secretary Xi Jinping’s status as the core of the party center and the entire party . . . .

In this passage we can clearly see, despite the thickness of the rhetoric, the link between the protection of Xi Jinping’s “core” status and the reading and summarizing of the Party’s “century-long struggle.” It may be difficult to see what social and political changes lie ahead for China. But a new resolution re-framing the Party’s history is not difficult to foresee – and history has certainly shown that such political acts can have profound implications.

__________

Who is Li Guangman?

Li Guangman has described himself as a columnist for CWZG.cn (察网) – which describes itself on its Weibo account as“the most influential patriotic portal in the country,” despite the fact that its URL seems inactive – and as an editor and freelance journalist. He also claims to be involved with the Kunlunce Research Center (昆仑策研究院), an online platform that claims association with the likes of political scientist Zhang Weiwei (张为为), who led the June collective study session of China’s Politburo, and Guo Songmin (郭松民), a leftist commentator and former air force pilot who has repeatedly raged against “historical nihilists.”