China Newspeak

“Hostile Forces” in the Digital Age

Screenshot of an image from the China House NGO showing its activities in Africa, included in a recent video attacking the organization.

Terms like “foreign forces” and “hostile forces” have frequently been used by Chinese Communist Party officials and domestic media over past decades to launch allegations of foreign interference, but these terms have often pointed not to real instances of external meddling but rather have underscored tensions within Chinese society. In the era of digital social media, when online flag-wavers can crowd-source their activities and self-publish their accusations, the discourse of foreign interference has become a regular feature of online attacks in Chinese cyberspace, with a wide range of groups and individuals denounced as traitors.

One such unfortunate instance unfolded in late October, just as world leaders prepared to meet in Glasgow to address the issue of climate change. The Chinese NGO China House, an independent Shanghai-based educational social enterprise founded in 2014 that aims to “further integrate China into global sustainable development efforts through youth engagement,” including over environmental issues, faced a storm of harassment after an online influencer accused it of producing content allegedly used by “foreign forces,” or jingwai shili (境外势力), to disparage China.

The storm began on October 26, as a 13-minute video was posted to Weibo by the account “Sai Lei Three Minutes (赛雷三分钟), which often features short explanatory videos on topics ranging from world history to politics and cars. The video, produced by “Sai Lei Hua Jin” (赛雷话金), accused China House of recruiting student volunteers in order to produce “finger-pointing” negative content that “Western media can use to smear China.” Various forms of engagement between China House and foreign partners, including the China-Africa Project and the World Wildlife Fund, were characterized by the video as instances of the NGO working with “outside forces.” The video concluded by alleging that China House “served as a mouthpiece for the West in brainwashing Chinese” and producing “anti-China content” (反华内容).

The video took issue, for example, with the NGO’s work on discrimination against African migrants in Guangzhou, and with its nuanced views on racism. Among many others, it cited a research article from the organization headlined: “Discrimination Against Black People is Not Just an American Issue: Chinese Must Also Be on Guard.”

The post from “Sai Lei Hua Jin” quickly received more than 20 thousand reposts and more than 50 thousand likes, with many internet users similarly venting their outrage, accusing the NGO of damaging China’s reputation. In the days that followed, similar posts claiming to unmask China House as working with “outside forces” appeared across the internet. And the attention triggered a wide range of online attacks and doxxing against staff from the NGO.

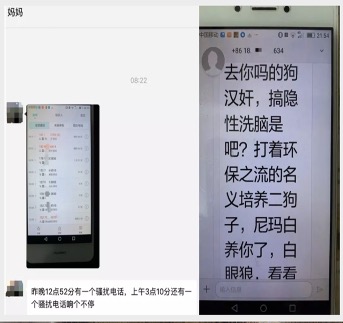

The founder of China House, Huang Hongxiang (黄泓翔), a graduate of Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, issued a statement via WeChat in which he countered the allegations against the NGO and shared harassing messages the organization and its staff members had received. Huang even shared threatening messages his mother had received. One message read: “Damn you, traitor! So you are carrying out furtive brainwashing, eh? In the name of environmental protection, you are raising the next generation of dogs.”

The attack subsequently spread to another NGO called Common Future, found to be following China House on Bilibili, the video sharing website based in Shanghai. One Chinese university student who as a volunteer at “Common Future” had produced a video on the refugee issue revealed in a post to the Douban platform that she was facing cyber-bullying as a result of the “Sai Lei Hua Jin” video. In her post, the student said that her social media accounts on QQ, Weibo, Douban and Wechat had been flooded with curses from netizens, condemning her for “taking money from the West to smear China.”

The volunteer’s article detailing her harassment was deleted by a platform regulator the next day. The comments attacking her remained, however. In the comment section of the video she had produced for Common Future, the volunteer was trolled with the words “50w,” an online reference to the 500-thousand-yuan reward that citizens can claim for reporting actionable instances of espionage to the Ministry of State Security (MSS). “Let me take my 50w home,” one user wrote again and again with smiley face emoticons.

The former volunteer at Common Future told CMP that influencers like “Sai Lei Hua Jin” produce videos like the one attacking China House in part because they can be extremely successful in attracting views online. “It is like they have found the key to getting video views,” the volunteer said, “so of course they will continue making videos like this, playing the heroic NGO hunter.” On November 1, another post to the Weibo account “Sai Lei Three Minutes” alerted viewers that another “investigation” of China House and its alleged connections with “foreign forces” would be released in early December.

Topics related to nationalism and the defense of China’s dignity can often prove popular on social media, and are a safe and surefire way to generate traffic in an environment where other current affairs issues can be highly risky. The popular scientific video channel PaperClip (回形针) learned this painfully in March last year when one of its videos posted to YouTube failed to include Taiwan as part of China, drawing outrage from netizens and eventually prompting an apology from the producer, Wu Songlei. PaperClip also faced criticism as online influencers, including “Sai Lei Hua Jin,” dug into former employees of the video channel and highlighted their supposedly “anti-China” remarks, as well alleging that one former employee had subsequently worked for a US military facility.

The use of accusations of foreign collusion to target domestic dissent has a long history. The term “hostile forces” (敌对势力), in fact, has its origins in Mao Zedong’s infamous February 1957 speech on “internal contradictions among the people,” which came ahead of the Anti-Rightist Movement that sentenced millions of writers, journalists, artists and teachers to “re-education through labor” and other punishments. In his speech, Mao Zedong outlined the need to “clearly distinguish between ourselves and the enemy, between right and wrong.” Under Mao’s system of “democratic centralism,” there were “the people” (人民) and those who fell outside this designation owing to their political crimes. “So long as they are not enemies, they are the people, and within this purview there can be no question of dictatorship,” said Mao.

The term “hostile forces” rose to prominence during the political struggles several years later, in 1959, as a catchall phrase for the Party’s enemies, both internal and external. Such forms of “aggressive discourse,” tend to be used with greater intensity in times of real or perceived vulnerability for the Chinese leadership. For example, historical peaks for “hostile forces” in the People’s Daily include the period after June 1989, and the period during the crackdown on the Falun Gong spiritual movement in 1999. The term “hostile forces” can be deployed against unspecified foreign enemies, or against domestic enemies both inside and outside the Party.

The term “foreign forces” began appearing in the 1990s, often combined with the phrase “hostile forces” as “foreign hostile forces,” and was used with slightly increasing frequency in the 2000s, often with the accusation that religion was being used to “infiltrate” China. “Foreign forces” seems to appear with greater frequency as a term on its own, without the addition of words like “hostile” or “separatist,” in the Xi Jinping era. It was used, for example, to refer to events in Hong Kong around the 2014 Occupy Central movement.

Use of “foreign forces” in the official People’s Daily newspaper was infrequent in both 2018 and 2019, when it appeared just four and three times respectively. But the term leapt dramatically in 2020 in the paper, appearing in 65 articles for the year, the peak coming with the July 2020 introduction of National Security Law in Hong Kong. “Foreign forces” has appeared in 17 articles in the People’s Daily so far in 2021.

The discourse around “foreign forces” often deals with reporting on China by international media, with “Western media” (and those dealing in any way with them) frequently the target of criticism. In an article in the People’s Daily in April 2018, Zhao Qiang (赵强), the deputy editor of the Global Times newspaper, wrote that “interfering in the internal affairs of other countries through various means is something that Western countries are always willing to do, and one of the most common and practical methods is to infiltrate public opinion by raising the banner of so-called ‘freedom of the press.’”

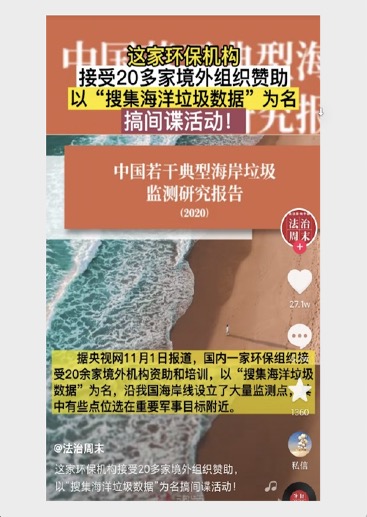

Allegations like those against China House are increasingly common on China’s internet, where nationalistic users are on the hunt for perceived slights against the national image. In some cases, these actions are shared by official state media. So far, the online allegations against China House have not been reported by state media in China. However, the People’s Daily did make a post to its official Weibo account on November 3 claiming that a Shanghai-based environmental NGO, which it said received overseas funding, had been collecting marine data such as wind speeds and water temperature around military bases and naval vessel routes while monitoring marine waste.

The post did not identify the NGO by name, but speculation on social media soon centered on Rendu Ocean, an organization focused on marine environmental protection actions, and internet posts soon appeared accusing Rendu Ocean of espionage activities on the basis of its engagement with more than 20 “foreign organizations.”

Following the release of the video earlier in 2021 by “Sai Lei Three Minutes” that alleged connections between PaperClip and foreign organizations, the former was praised in June by Jun Zhengping (钧正平), a social media account launched in 2016 by the People’s Liberation Army in order to “innovate the army’s work in propaganda, ideology and culture.” The account warned in a post that China had to be aware of foreign NGOs that “cooperate with domestic self-publishers to place videos containing ideological ‘private goods,’” all in the name of environmental protection.

“There is no national security without cyber security,” the post said. “Maybe the ‘friend’ you are interacting with is a spy of some foreign intelligence agency. You must be careful. Every Chinese internet user and every Chinese internet company must keep their eyes open and not forget their responsibility in maintaining the country’s cyber security.”