Song Gengyi, a journalism instructor who was fired from her job at Shanghai’s Aurora College on December 16.

The firing on Thursday of a teacher at a vocational college in Shanghai who, according to state media made the “erroneous remarks” on the number of victims of the 1937 Nanjing Massacre, has prompted a fierce struggle online over the right to explore historical truths. But censorship by the authorities has effectively silenced voices in support of the teacher, sending the message that nuance about CCP orthodoxy on history will not be accepted – and that teachers should beware of student informants in the classroom.

The storm began on December 15 as a short video circulated online – apparently shared by a student “informant” – of a lecture in which Song Gengyi (宋庚一) questioned the 300,000 official number given by the Chinese government for the number of victims in the Nanjing Massacre, a tragedy that unfolded on December 13, 1937, as the Imperial Japanese Army captured the capital city of Nanjing during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Song made the remarks during her December 14 “News Interview” (新闻采访) course at Shanghai’s Aurora College, held the day after nationwide commemoration of the massacre’s anniversary.

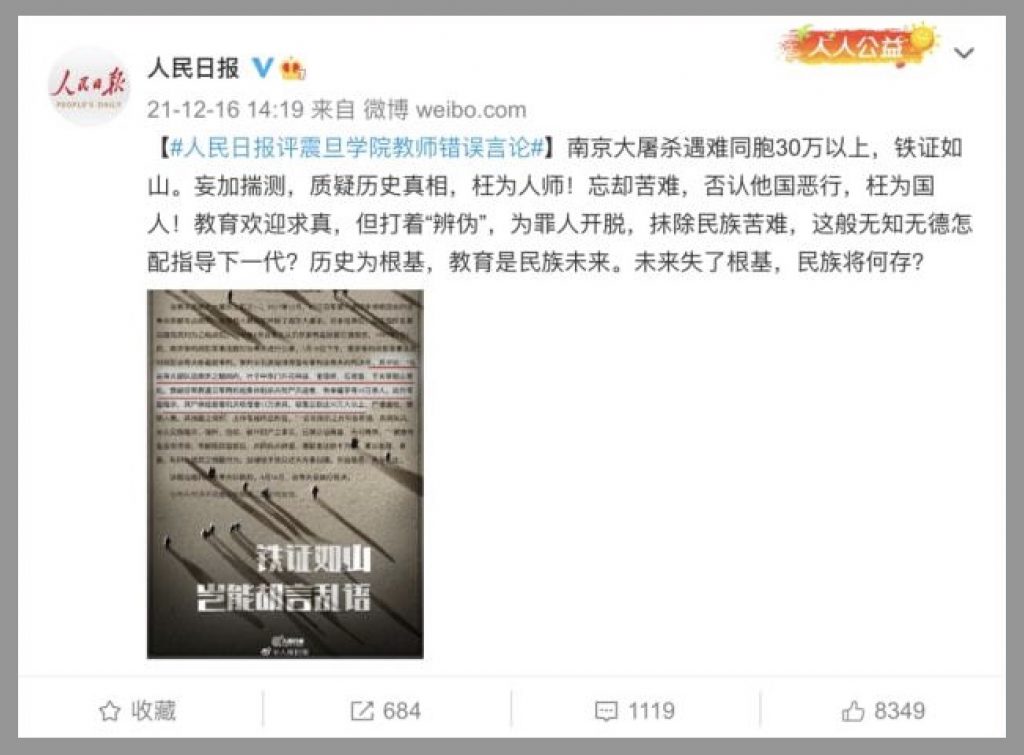

On the afternoon of Thursday, December 16, the official Weibo account of the People’s Daily, the CCP’s flagship newspaper, weighed in on Song’s remarks. The tone of the post, which called the 300,000 number “iron-clad fact” (铁证如山), was severe. It said that Song was “errant as a teacher” (枉为人师) for “questioning historical truth,” and that she was “errant as a compatriot” (枉为国人) for “forgetting hardships and denying the evil deeds of another country.”

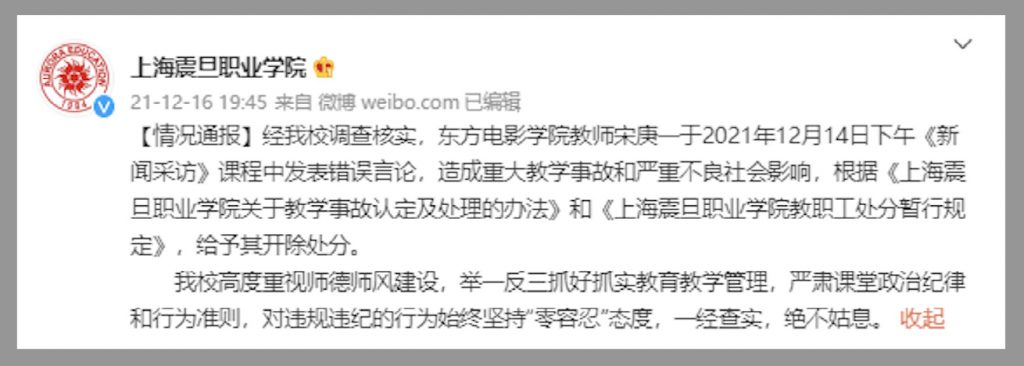

Within hours news came of Song’s firing. According to a notice issued on Thursday evening by Aurora College, Song, whose position was formally with the college’s Eastern Film Academy (东方电影学院), had “spoken erroneously” (错误言论) during her class on news reporting, and had been fired on the grounds that the incident had been “a major teaching accident generating a serious negative social impact.” She had been fired, the notice said, on the basis of two internal college guidelines, on disciplinary measures for teaching staff and on the “handling of teaching accidents” (教学事故).

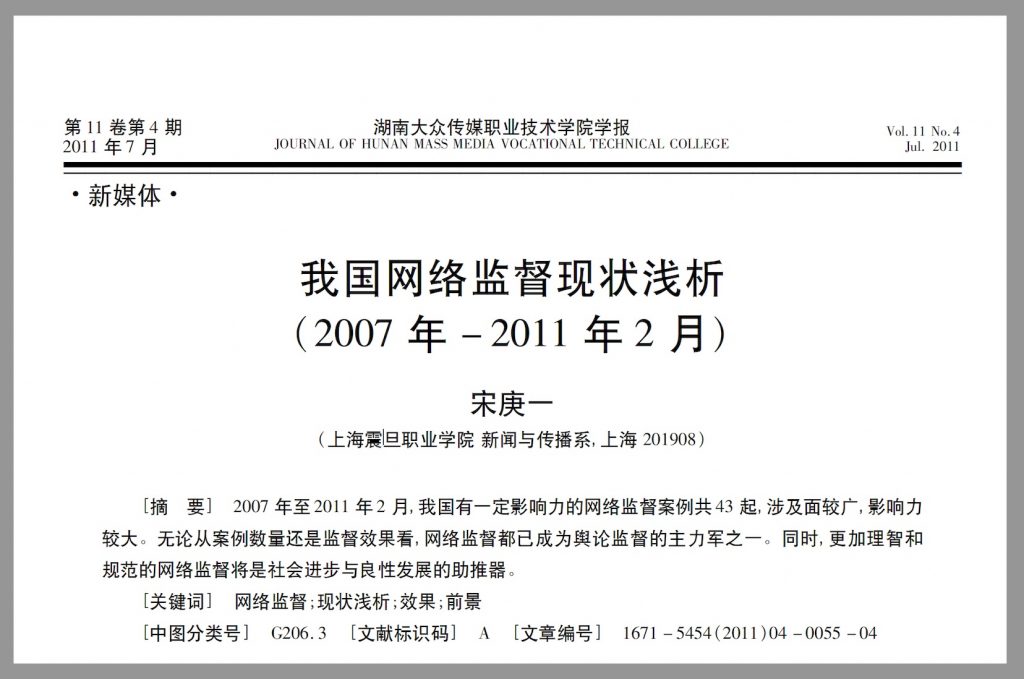

Song is a veteran journalist who has served as the deputy head of the journalism and communication program at Aurora College (震旦学院), a vocational college founded in Shanghai’s French Concession in 1905 by Chinese Jesuit Mao Xiangbao (馬相伯). In addition to teaching, she has published academically on communications, including a 2019 paper on the impact of “network supervision” (网络监督) in calling attention, and sometimes driving remediation, in cases of social injustice.

In her paper, Song concluded that “rational and standardized” network supervision, meaning the posting through social media and other channels of cases of malfeasance and unfairness, “would promote social development and progress.” But she ended the paper with a caution that now seems prescient given her case. “Where network supervision is concerned, online violence cannot be ignored,” she wrote. “In replies to many hot-button issues on the internet, the words of netizens often include violent language such as ‘die’ or ‘kill,’ or employ obscene language. The internet has become an outlet for emotions. Network supervision has become a pressure valve for emotions, lacking rationality, and in some cases has even led to ‘internet trials’ (网络审判) that impact judicial justice.”

Mirroring the process she describes in her paper, criticism of Song was swift, vicious and retributive. Online nationalists pried into her past, posted her personal information online, and called her a “traitor.” One post over the weekend referred to Song and other “public intellectuals” (公知) as “pests” hiding amongst the people.

But Friday, however, voices in support of Song Gengyi were swelling too. Protests against the injustice of Song’s treatment grew in volume as a full version of the classroom video was circulated, giving her remarks fuller context. It clearly showed Song discussing the verification of historical facts as possible and important, characterizing the 300,000 figure as arising from a particular historical and political context – and making the point that more could probably be discovered, with proper research, about even the specific identities of the victims. Nothing seemed to show Song in any way minimizing the Nanjing Massacre or its historical importance. A number of media veterans in particular voiced their support for Song. Pursuing the facts, they said, was the first rule of journalism, and Song’s attitude showed a strong respect for academic rigor.

Many of these voices were quickly removed from the internet, even as posts and comments attacking Song Gengyi proliferated. Legal experts, meanwhile, took to social media to encourage Song Gengyi to take legal action against Aurora College. Yan Tong (冉彤), a Chinese rights lawyer, told RFA: “Everyone feels that this was a normal way of teaching. It’s just that right now, leftist trends in society are on the rise, and teachers who speak the truth are seen as having problems.”

Several lawyers, Yan said, had tried to reach Song to offer legal representation, but she could not be located – a possible sign, they felt, that she had been detained and was being kept away from the media.

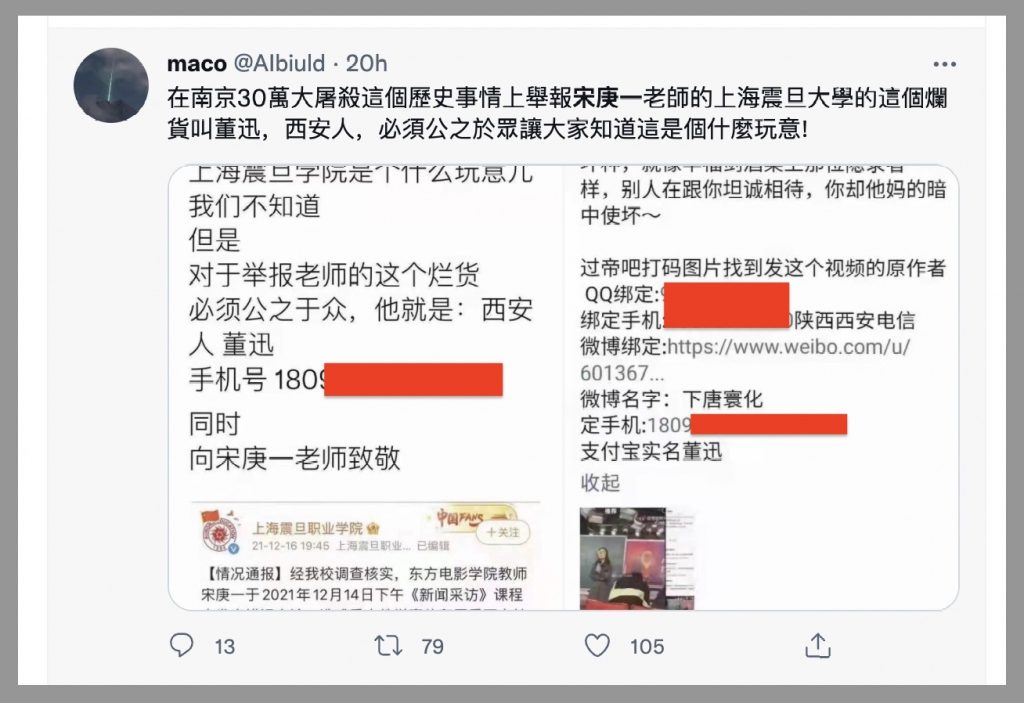

By Friday also, the attacks on Song Gengyi prompted a “human flesh search engine” (人肉搜索) wave counter-attacking the student alleged to have informed on the teacher. Personal information about one suspected student, identified as “Dong Xun,” was posted on social media in China and overseas, calling on others to dig deeper and to “let the world know.” The following post to Twitter, one of hundreds appearing Friday, shared the student’s mobile number and social media account details, calling them “rotten goods” (烂货).

Many posts on Twitter were personal attacks on Dong Xun, calling for retribution. At least one post, however, pointed out that the online struggle between the two sides was a distraction from real causes. “Dong Xun directly destroyed a teacher, school leaders indirectly destroyed a teacher, and so we all go and destroy a student together?” one user wrote. “Why don’t we destroy these ruinous rules instead?”

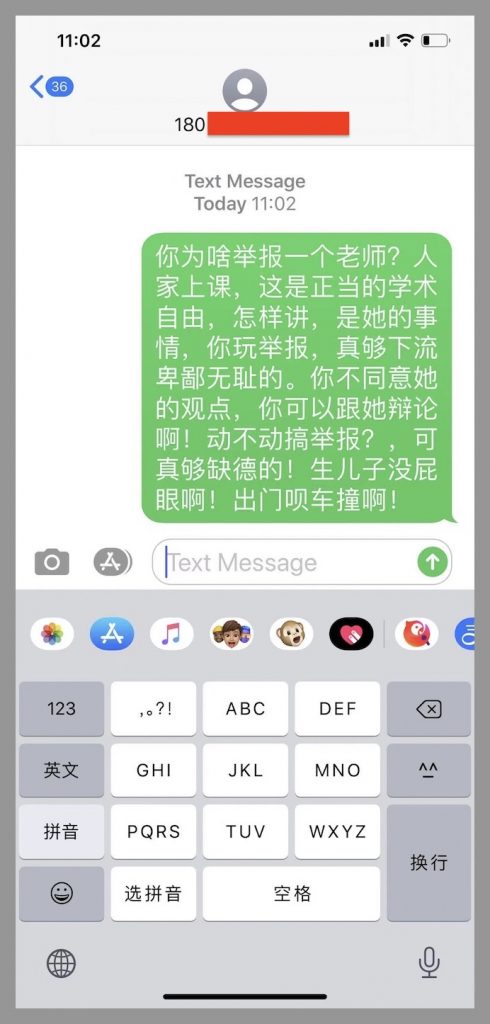

The post shared the screenshot of a text apparently sent to Dong Xun on the student’s now very public personal mobile number:

Why did you inform on a teacher? People going to class is a normal form of academic freedom, and how they speak is their own business. You playing this informing game is so crude, disgusting and shameless. If you don’t agree with her views then you can have a discussion! Why must you inform! This is so immoral!

“Dong Xun is a beast, not a human being,” another Chinese user wrote on Twitter.

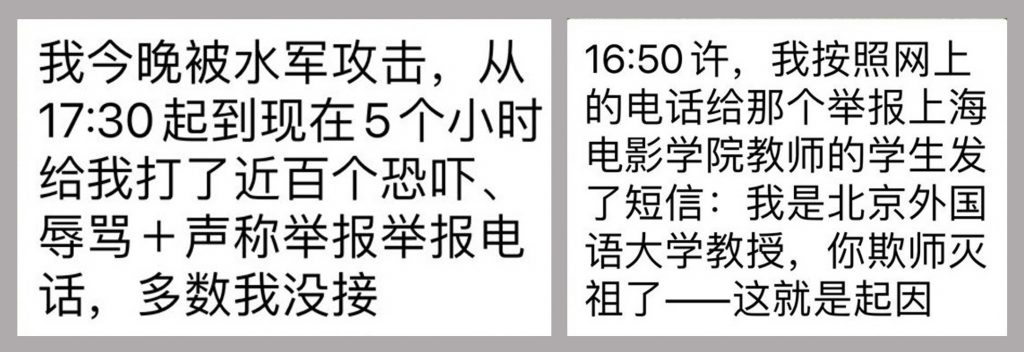

In addition to the human flesh search against the student thought to have been behind the campaign against Song Gengyi, a number of prominent academics and journalists apparently reached out to reprimand the student through the mobile number provided online. According to one professor, whose communications were viewed by CMP, they suffered a wave of counter-attacks online, including posting of their own personal information, after sending a text to the student’s number.

“At around 4:50PM I sent a message to the student informing on the Shanghai film academy professor according to the mobile number online, saying they had engaged in shameful bullying,” the professor wrote. “Tonight I’ve been attacked by spammers, getting close to a hundred calls threatening and cursing me, and saying they are reporting me.”

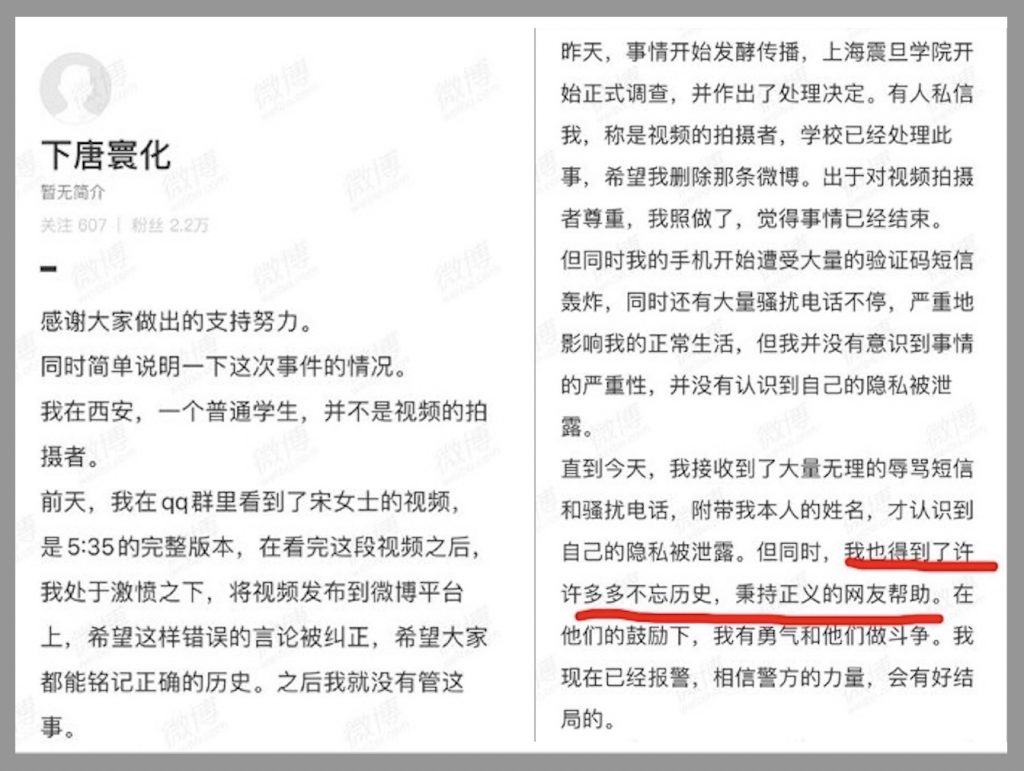

Late on Friday, the student accused of informing on Song Gengyi made a post to Weibo in which they attempted to explain their decision to post the video that had kicked up the storm to begin with. They explained that they were an “ordinary student” in Xi’an, and that they had not in fact taken the video in question.

The day before yesterday, I saw the video of Ms. Song in a QQ chat, the full 5:35 [minute] version. And after watching the video, really angry, I posted it to Weibo, hoping that these erroneous remarks [from Ms. Song] could be corrected, hoping to engrave a correct view of history. Afterward, I paid no attention.

Yesterday, the matter started to accelerate, and Aurora College started to investigate, making the decision to handle it. Someone sent me a private message saying they had taken the video, that the school was already handling the matter, and that they hoped I could delete my Weibo post. Out of respect for the video source, that’s what I did, thinking this would end things.

But my mobile started exploding with messages, and at the same time the trolling telephone calls came non-stop, seriously impacting my normal life. But I didn’t realize the seriousness of the matter, and I didn’t realize my privacy had been violated. It was only today, as I received an endless number of disturbing messages and trolling calls, that I realized my privacy had been violated. At the same time, I received a lot of help from many web users who have not forgotten history and who uphold justice. With their help I had the courage to struggle against them. I have already notified the police, and I’m sure with their power this matter will end.

China’s Party-state media, including official public accounts such as that of the People’s Daily, have issued no further response on the Song Gengyi case since last Thursday, despite the fact that a fuller account has emerged, putting the short video in context, and despite that fact that more people have spoken up in support of Song. Meanwhile, voices supporting Song continue to be removed from social media, while accounts of her allegedly “erroneous remarks” are apparently allowed to remain.

In post to WeChat about Song’s case on Friday, Wang Yongzhi (王永智), who writes under the penname “Wang Wusi” (王五四), said the current public opinion climate in China was “pandemonium,” and that while “reasonable people dare not speak out at all, unreasonable people constantly point to deer and called them horses, with no reason and no sense of the law.”

The simple words, ‘You are not patriotic,’ can lead to a thousand accusations, and nothing you say makes any difference,” said Wang.

That post too has now been deleted.

Those interested in learning more about the recent history of students informing on their teachers for political transgressions, and about the formal system of “student informants,” can turn to CMP’s 2018 article, “Informants in the Chinese Classroom.”