The headquarters of China Central Television in Beijing. Image by Ian Holton available at Flickr.com under CC license.

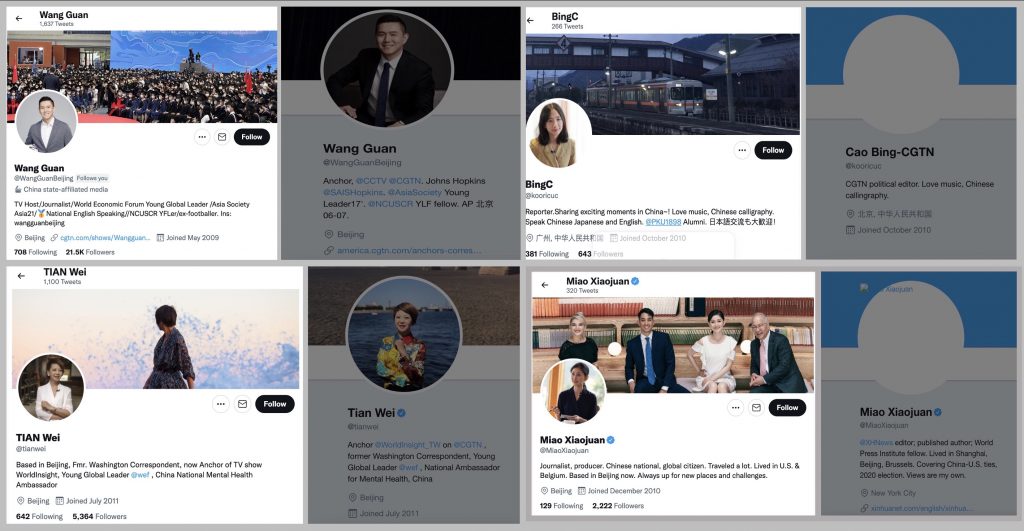

Anyone stumbling across the profiles of Miao Xiaojuan on Western social media platforms will gain a glimpse into the life of a Chinese journalist who spends a great deal of time on the road, visiting far-flung regions throughout the country, each more beautiful and peaceful than the next.

At first glance, Miao’s perspectives and experiences seem largely personal. In her Twitter bio, she identifies herself simply as “Journalist, producer,” adding that she is a “Chinese national” and a “global citizen” – based in Beijing but “[always] up for new places and challenges.” On Facebook, she is simply “a journalist in China.” Her posts also seem to have been popular, earning her more than half a million followers on Facebook, the kind of personal reach most working journalists can only dream of.

But Miao’s social media presence outside China is also somewhat misleading, contributing to the ongoing debate in the West about efforts by the Chinese state to influence the discourse on China globally, or even to sow disinformation, through platforms like Facebook and Twitter. When are social media accounts personal? And when are they being disingenuous about the state agendas they serve?

Miao is one of at least a dozen Chinese journalists working for state-run media outlets who are active on Western social media platforms without mentioning who they work for, maintaining ostensibly personal accounts that closely mirror Party-state agendas. Reporting and commentary from official sources makes clear that this fits an explicit strategy of exploiting the ambiguity of such “personal brands” for the conduct of external propaganda. And several of the journalists have expanded their potential reach by running ads on Twitter and Facebook promising unbiased views of China, a claim to straightforwardness betrayed by being vague about their actual employers.

Changing Profiles

Miao Xiaojuan is the host of a show called “China Chat,” produced by the country’s official Xinhua News Agency. The show routinely highlights praise for the government in ways that would make many professional journalists uneasy. “What always impresses me about China is that these kinds of fairs that are actually state-backed,” a Shanghai-based public relations executive says in one segment on a trade expo. “I think that really speaks to how much the government is really sponsoring and supporting these kinds of commercial initiatives to drive the economy.” Immediately after, another source piles on the praise: “What I do see here is the Chinese government saying the door is open.”

Twitter, Facebook, and their competitors have stepped up efforts to limit the reach of Chinese state media on their platforms, and an earlier investigation by CMP showed that Twitter’s labeling of state media, including the limiting of access to advertising features, made their posts less popular among followers. But a closer look at social media accounts suggests that state media employees continue to share government viewpoints while trying to avoid the scrutiny that might arise from an overt connection to state media.

In at least six cases, Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine shows Chinese state media journalists removing mentions of their employers from their social media bios. Miao’s introduction on Twitter, where she routinely promotes “China Chat” content like the above, once began with “@XHNews editor,” making clear that she is an employee for Xinhua. But sometime over the last two years, this basic act of journalistic transparency on Twitter disappeared.

In at least six cases, Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine shows Chinese state media journalists removing mentions of their employers from their social media bios.

Similarly, Wang Guan, the chief US correspondent for CGTN, the foreign-facing department of state broadcaster CCTV, describes himself as a “TV Host/Journalist” on Twitter. A previous version of his bio said “Anchor, @CCTV @CGTN.” His colleagues Tian Wei and Cao Bing, who have relatively fewer followers, have done the same. Ren Ke, a Xinhua reporter based in Europe, used to describe himself as “Correspondent of China’s Xinhua News Agency in Berlin.” Now, his profile just says “Chinese correspondent in Europe.”

It is generally considered ethical practice in the West for those working for news media to identify their affiliations clearly in their social media profiles. For example, the Associated Press states in its “Social Media Guidelines” that employees “must identify themselves as being from AP if they are using their accounts for work in any way.” Employees need not include AP in their usernames, and should use personal images rather than the AP logo for profile photos. “But you should identify yourself in your profile as an AP staffer,” the guidelines say.

Speaking for Peng Shuai

Perhaps the most well-known state media employee to have been ambiguous about his employer is Shen Shiwei, the CGTN editor who in November shared the photos and videos meant to assuage worries about the well-being of Chinese tennis star Peng Shuai, who was not heard from for weeks after she accused former vice premier Zhang Gaoli of sexual assault in a post to the Chinese microblogging platform Weibo. Shen’s posts were part of what seemed to be a concerted, though often sloppily staged, campaign on American social media to diminish concerns about Peng Shuai.

Shen’s current Twitter bio is a jumble of descriptions that leave out what it plainly said two years ago: “Int’l Editor of CGTN.”

Among the state media employees identified by CMP as having removed affiliations from their social media profiles, some (like Shen) are marked by either Facebook, Twitter, or both, as being “China state-affiliated media.” Such labelling is perhaps what they had hoped to avoid by omitting mention of their employers over the past two years.

But some accounts have managed to avoid the labels, applied by Facebook and Twitter in the interest of transparency. And this act of flying under the radar has enabled the accounts to increase their reach by purchasing visibility through the platforms. On Twitter, the “state-affiliated media” label makes paid promotion unavailable. Facebook restricts state media-affiliated accounts from running ads targeting American users to protect the elections process in the United States, but does allow them to target users in other countries, where concern over possible foreign interference in elections has not prompted the same level of public debate.

All in all, nine state media employees identified by CMP have managed to grow the reach of their profiles by paying for ads. Miao’s impressive Facebook following, for example, was likely built by the about 60 ads she has run since opening her page in January of last year, Facebook’s Ad Library shows.

Taking the “Public Opinion War” to Twitter

In some cases, journalists for Chinese state-run media promoting themselves as independent voices on social media platforms outside China, and blocked at home, have been openly promoted in official sources as innovators in “telling China’s story well” (讲好中国的故事), a phrase that now encapsulates the Chinese Communist Party’s strategy for influencing the discourse on China globally, what the CCP typically calls “external propaganda” (外宣).

Xu Zeyu, a reporter for Xinhua — or just a “Chinese journalist,” as he says on his profile on Facebook, where he has close to 3 million followers — has openly promoted an image inside China as an expert on strategies for “telling China’s story well,” a priority that was the focus of a collective study session of the Politburo back on May 31, 2021 (CMP coverage here).

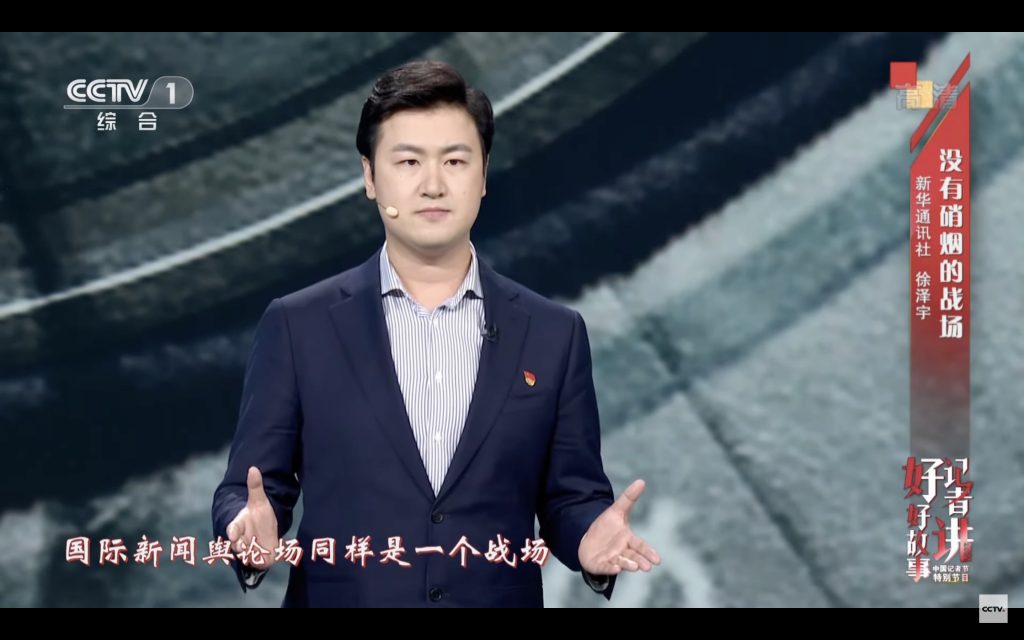

On November 8, 2021, in commemoration of Chinese Journalists’ Day, Xu was invited to deliver a talk on China Central Television in which he was open about his use of foreign social media to counter misconceptions about China. In the segment, Xu mirrored official CCP talking points about China being engaged in a “public opinion war” globally. “The international discourse sphere is also a battlefield. This battlefield may not have guns and bullets or the smoke of war, but it has right and wrong,” Xu said.

Describing his camera lens as a weapon in his struggle for the nation, Xu explained how he had used foreign social media to draw attention to his English-language “vlog” reports singing the praises of first responders in the midst of the Covid-19 epidemic in Wuhan.

But another of Xu’s weapons has apparently been his use of ads to build up his overseas following and more widely disseminate his reports. He has run 25 ads on Facebook, the latest two ads appearing on January 4 this year. Some of these ads focus on particular official news stories, such as President Xi Jinping’s visit to a rural village around Spring Festival in 2021. Others promise a “different angle” on Chinese society. Xu’s most recent ad shared images of the ski jump venue for the Beijing Winter Olympics. Such content is arguably harmless, but the ad buying behind it has the effect of bolstering attention to a Facebook page and linked social media accounts that can, when necessary, be blatant channels for provocative content and disinformation.

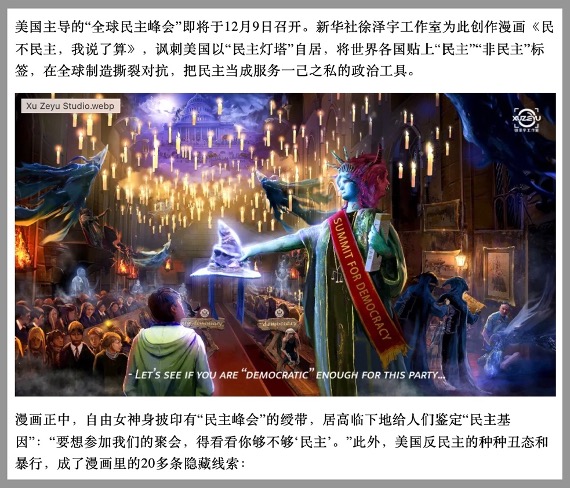

On December 10, 2021, as the US held its Summit for Democracy, Xu posted a high-polish illustration to Facebook of a Mordoresque landscape of destruction, with the US Capitol Building sitting atop a mountain of fire. The unmistakable message of the image – which was captioned “Climbing the Summit for ‘Democracy’” – was about the falsehood and hypocrisy of American democratic values, a theme that dominated headlines in Party-state media in November and December, in the weeks ahead of the US-led summit.

The illustration on Xu’s Facebook page was attributed to “Xu Zeyu Studio” (徐泽宇工作室). As Xinhua has itself reported, the “Xu Zeyu Studio” was “specially set up” by the agency at the end of 2020, to “be responsible for account content planning and production, and overseas landing promotion.” Moreover, the report said, the establishment of the studio had enabled “better use of the strength of [the Xinhua] team” and “strengthening of cross-departmental cooperation.”

Describing his camera lens as a weapon in his struggle for the nation, Xu explained how he had used foreign social media to draw attention to his English-language reports.

The “Xu Zeyu Studio” is meant to capitalize on Xu’s position as an “international influencer” (国际网红), enabling more effective dissemination of Party-state propaganda, including more viral forms of soft propaganda. In a paper published in July 2021 in China Journalist (中国记者), a Xinhua publication that is a flag bearer for the official state-run press, this operationalizing of the personal accounts of state media journalists like Xu was clearly identified as an explicit strategy.

The paper, “Xu Zeyu Studio: Using Personal Brands to Innovate the Overseas Public Opinion Struggle,” took an in-depth look at the rapid development of Xu Zeyu’s personal accounts on overseas social media beginning in February 2020, just as the Covid outbreak was at its most severe in China, and culminating in Xinhua’s creation of the “Xu Zeyu Studio.” It mapped Xu’s connections to a wide range of people and institutions active on overseas social media, and advocated for greater utilization of the “personal brands” (个人IP) of “individual netizens” – meaning known and trusted personal account holders with Party-state affiliation or affinity – as an effective strategy for external propaganda:

In the future, the official accounts of central media and individual netizens should further strengthen communication interaction with the accounts of our diplomats, embassies and consulates abroad, with Chinese and overseas Chinese groups, with international student groups, pro-China media, pro-China scholars, international organizations, research institutions and other opinion leaders. In particular, individual netizen accounts should be more flexible and personalized, and should strive to become friends with opinion leaders in different fields and circles, so as to expand their own circle of friends in the overseas media and explore communication resonance.

One example of such “communication resonance” cited by the Xinhua Daily Telegraph last month was another glossy illustration by the “Xu Zeyu Studio” satirizing the Summit for Democracy by likening it to the sorting hat ceremony at Hogwarts, with various spirits hovering around in the darkness that are meant to give shape the lie of American democracy.

“After the cartoon was posted on the overseas social media accounts of Xinhua’s Xu Zeyu,” the publication noted, “it attracted more than 2 million views and more than 40,000 likes from foreign netizens, who engaged in lively discussions about the cartoon’s symbolic meaning and the ‘Summit for Democracy’ itself.”

The Bid for Influencers

In addition to Xu Zeyu, CGTN employees Serena Dong, Li Jingjing, Wang Guan, Jessica Zang, and Rachel Zhou have also run paid promotions of their Facebook pages, helping give them a combined following of some six million users.

Back in January 2021, Twitter closed its Ads Transparency Center, making it harder to track paid posts on the site. But two Xinhua employees who remain label-less – Ren Ke, the Europe-based Xinhua reporter, and his China-based colleague Liu Fangqiang – appear to have run ads for their profiles, posting tweets through “Twitter for Advertisers.” One year ago, Ren tweeted: “Providing unique views & information about China. Follow me.” The post was promoted widely enough to rack up more than 600 retweets and over 7,000 likes. Back in August 2021, Liu Fangqiang promoted a tweet in which he promised to bring followers closer to a China not shown by Western mainstream media.

Social media users attracted by these ads will see content that doesn’t stray far from the Chinese government’s messaging. Between selfies and food photos, much of what Miao shares revolves around trips to Tibet and Xinjiang, focusing on travel as though none of the widely reported human rights violations were taking place in the two Chinese regions. Xu’s first Facebook ad promoted Hong Kong’s national security law as an unambiguously positive development.

Much of the activity of the above-mentioned accounts could certainly be construed as personal activity, reflecting genuinely held opinions, and none of the activities outlined above are illegal. But as Xinhua’s open reporting of Xu Zeyu’s social media presence overseas makes clear, mixing personal presence with the Party’s agenda is an actual strategy.

Back in July last year, Singapore’s Straits Times reported on how three of the state media employees mentioned above – CGTN colleagues Li Jingjing, Jessica Zang, and Rachel Zhou – were also part of a project by the state-run broadcaster to manufacture influencers. The paper reported, on the basis of interviews with current and former CGTN staff, that an “influencer studio” had been set up inside the broadcaster for the purpose of grooming such influencers.

CGTN is part of the China Media Group, a conglomerate created in 2018 to merge China’s major CCP-controlled media companies. In June 2021, the group’s chief, Shen Haixong, called for the creation of “a studio for influencers in multiple languages,” in order to seek new breakthroughs in “telling China’s story well.” As the China Journalist paper published soon after Shen’s call (and written by Xinhua insiders) makes clear, one important strategy is to ensure that “personal brands” help to amplify Party-state talking points while maintaining the semblance of distance. That means not mentioning, presumably, that influencers work for CGTN, Xinhua or other state media outlets.

In fact, Chinese state media, which face stringent controls under the mandate of CCP “public opinion guidance,” have always taken the management of the personal social media accounts of employees seriously. Earlier internal guidelines for microblog use by employees at one state media group, distributed in 2014 and viewed by CMP, specify that “[news] staff shall apply for approval and be put on file at their news media before opening accounts for blogs, microblogs, WeChat and others,” and that “their work units shall be responsible for daily supervision and management over them.” Aside from specifying responsibility in the organization’s General Office for “taking charge of the unified management of personal microblog[s] in the program publicity system,” the guidelines also instruct each channel to designate a “contact person” to “[take] charge of assisting the responsible person of the channel . . . . to manage and guide personal microblog behaviors.”

The guidelines make it patently clear that state media view employee activity on social media as a serious matter for daily oversight, and that mechanisms have long been in place for regular monitoring, enforcement and discipline. If the CCP’s public opinion controls as applied through the state media are to be taken seriously – which is of course a point Xi Jinping has himself stressed with greater force than his predecessors – what are the implications for the independence of personal social media accounts maintained by state media employees on platforms that are banned inside China?

Affiliation with state media does not mean, of course, that individual journalists are not personally motivated to counteract the bias they perceive in global discourse on China, a conviction that underlies the Party-state’s determination to enhance its “international discourse power.” Ren Ke, the Xinhua reporter, tweeted in September last year, “I’ve found that many self-claimed experts, journalists are posting bullshit, fake news and disinformation about #China! Disgusting!” He added, “I have to tweet more.” But he, too, seems to have decided the best way to convince foreigners is by hiding who he works for.

CMP Director David Bandurski contributed additional research for this article.