Image by Dan Nguyen available at Flickr.com under CC license.

As the lockdown in Shanghai enters its third week, first-hand accounts of the misery suffered by many of the city’s 26 million residents have fired across Chinese cyberspace. For many, the failings of the government response in China’s financial hub have called into question the country’s vaunted successes in dealing with the coronavirus pandemic. The failings have also deepened frustration online with those who continue, in the face of real suffering, to pander to China-can-do-no-wrong nationalism.

Two weeks ago, “Sai Lei Three Minutes” (赛雷三分钟), a popular Chinese blogger known for his mission to expose the alleged activities of “foreign hostile forces” working to smear China, posted to his 2.6 million followers on Weibo that he planned to release a video clip in which he had “baited” a journalist working for foreign media in China with a fake interview about conditions under Covid lockdown in the northern city of Changchun.

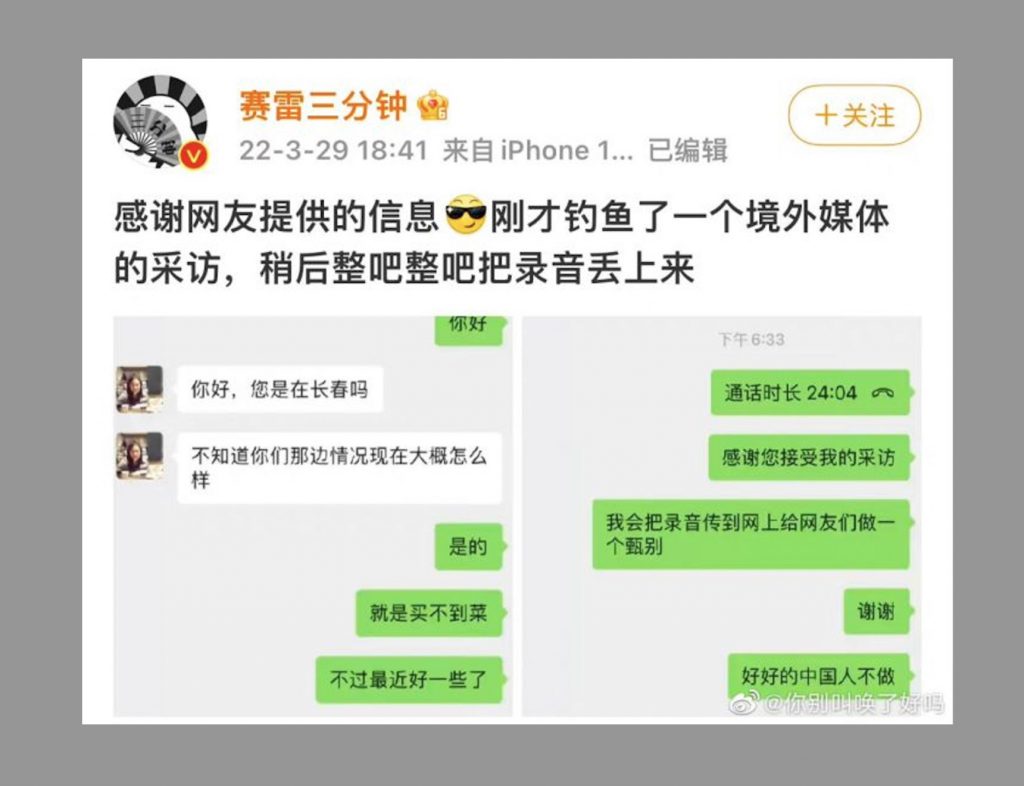

Sai Lei’s provocative Weibo post on March 29 included an image of his chat history on the WeChat messaging platform with a correspondent from Sveriges Radio, Sweden’s publicly funded radio broadcaster. The conversation showed Sai Lei impersonating a resident under lockdown in the city of Changchun, claiming to be unable to buy groceries. The Sveriges Radio journalist, understandably interested in the account of a source in the locked-down city, inquired about the situation and subsequently had a 24-minute conversation with Sai Lei, as shown by a “call duration” (通话时长) marker in the chat thread.

Immediately after the “interview,” Sai Lei posted to the journalist: “Thank you for accepting my interview. I will upload the audio to the internet to let netizens decide.” Sai Lei’s implication was that he would let his social media audience decide whether the journalist was engaged in the smearing of China.

Sai Lei, who has garnered a strong following online with his fast-paced videos and other posts claiming to expose foreign media prejudice and other instances of “anti-China” attacks, kicked up an online storm back in October 2021with a 13-minute video posted to Weibo that accused China House, an independent Shanghai-based educational social enterprise, of producing content allegedly used by “foreign forces,” or jingwai shili (境外势力) to disparage China. The video, which alleged that China House “served as a mouthpiece for the West in brainwashing Chinese” and producing “anti-China content” (反华内容), turned a wave of online harassment on China House staff and volunteers.

Earlier this year, after being interviewed by David Rennie of The Economist for an article on clickbait nationalism, Sai Lei went public with his own recording of the exchange, and fulminated against Rennie for trying to reveal his real identity, and for suggesting in his article that social media influencers like Sai Lei were cashing in on extreme nationalism. The headline of Sai Lei’s post: “I Accepted an Interview with the UK’s The Economist and Personally Experienced the Deep Malevolence.”

This time, however, as news of growing hardship under the conditions of Covid lockdown spread across the internet, Sai Lei’s Weibo announcement of the pending release of a major foreign media takedown landed with a thud. The reactions were apparently not what the blogger expected. His baiting of the reporter was swiftly condemned, some accusing him of pursuing online views over all ethical considerations. “Sai Lei keeps encouraging people to report on spies for 500,000 RMB rewards,” one comment read. “But I think he’s just a blogger hungry for attention who will do anything, including fake acts of patriotism, to get it.”

Others questioned the basic soundness of Sai Lei’s thinking. The blogger accused foreign journalists of selectively taking negative facts and sources to write stories about China, and in response he had purposely reached out to offer a foreign journalist negative facts and sources to support a story – that it had become impossible to buy food in Changchun – that by all accounts was true. In fact, the very same day as Sai Lei’s provocative Weibo post, the top leader of Changchun, Liu Renyuan, publicly apologized for food shortages that had affected the city’s 8.5 million residents.

As more reports emerged about the conditions in Changchun, Sai Lei deleted his original Weibo post and issued an apology in which he said that he had decided to hold off on the release of his recording after speaking to several residents in Changchun. Nevertheless, there was no attempt to apologize to the foreign journalist for impersonating a Changchun resident, and he insisted that Swedish media had a biased view of China. He added that he had shared his recording with the “relevant authorities.”

“I question the objectivity of these media on the basis of their sampling of negative comments, which I think also determines the viewpoint they ultimately take in their reports,” Sai Lei wrote. “Their so-called ‘objectivity and neutrality’ are just a facade.”

Before long, Sai Lei had deleted this apology. For some internet users, this was just too much: “So [after his recording] he finds that you really can’t buy food in Changchun, and having weirdly become the one handing the knife to foreign forces he immediately issues an apology,” one user wrote. “Now even the apology is deleted. This is so ridiculous.”

“This is the inevitable outcome of internalizing external propaganda,” another user responded, referencing a phrase for how China’s push for positive international perception has in many cases devolved into superficially patriotic fervor domestically and showed an uglier side of Chinese nationalism (See CMP’s “Putting the Soft Back in Soft Power”).

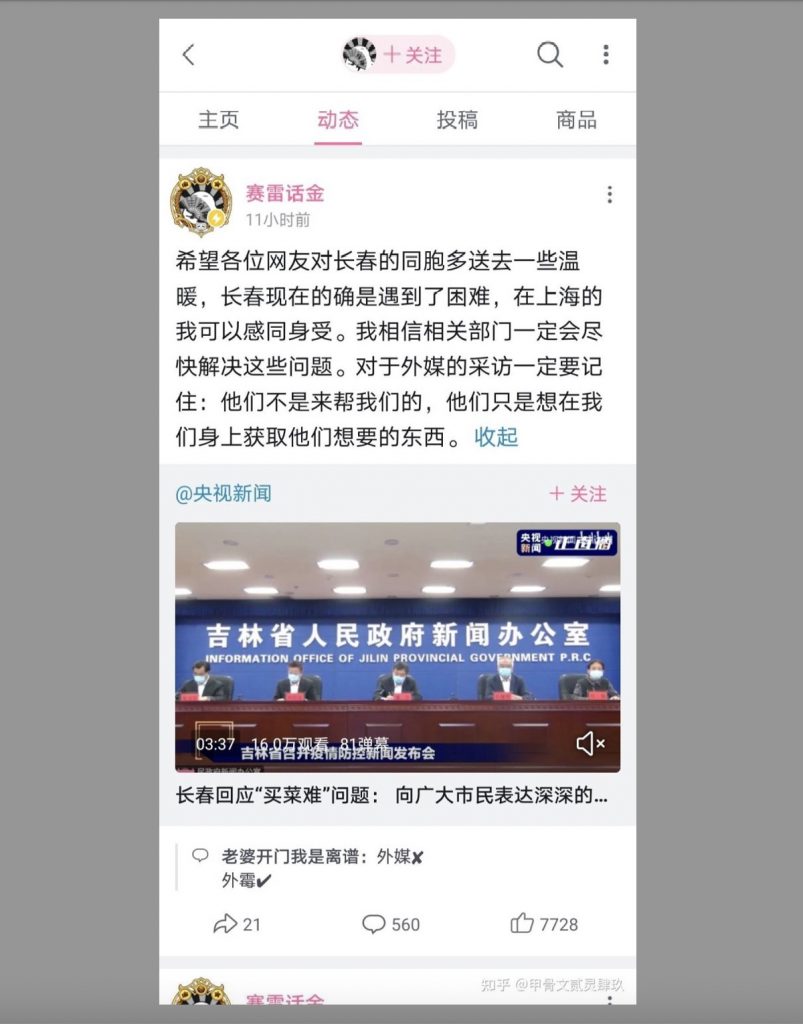

After deleting his original post and apology, Sai Lei turned to reposting content about coronavirus prevention in Changchun. On his account on BiliBili, the video sharing platform, he reposted content from the state-run China Central Television on the Covid-19 related government press conference in Changchun. Even though currently in Shanghai, he said, he could understand the hardships people were enduring in Changchun. And he urged confidence in the government response. “I’m confident that the relevant authorities will ultimately be able to resolve these issues,” he said.

But he could not resist adding a characteristic barb against foreign media. “Concerning foreign media interviews, we must be very careful,” he said. “They are not here to help us. They are just taking what they need from us.”

In the past, Sai Lei has gained a wide audience for his ostensible investigations into foreign media and civil society organizations with alleged foreign ties. But the recent backlash against Sai Lei’s viral vigilante approach to supposed negative coverage of China is perhaps a reminder that nationalist and anti-Western voices do not represent the ethos of Chinese cyberspace, and that there is some interest in greater honesty about China’s shortcomings.

“Sai Lei’s audience is clear,” one user offered in criticism. “They are little aspiring Marxists who take pride in looking down on the world. Our TV stations can broadcast news about shootings in the US, our radio can talk about the pandemic around the world, and our news can report on snowstorms in Texas. But when foreign TV stations come to interview us, we bait them, we cheat, and we advertise 500-thousand yuan [awards for reporting them as spies]. We belittle them, and yet we do so under this banner that says, ‘They see us only with prejudice.’”