Image of the new “county-level media convergence center” in Pizhou, Gansu province.

Tucked away in south-central Gansu province, rural Zhang County (漳县) could scarcely be more remote from China’s media centers in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. The only claim to fame in the thinly populated county, which has been designated as a priority area for poverty alleviation, is to have been called the country’s “home of the fava bean” (中国蚕豆之乡).

But Zhang County is nonetheless an important piece in the national puzzle of “media convergence,” or rongmeiti (融媒体), a process by which the Chinese Communist Party aims to consolidate its hold on information throughout society.

Earlier this month, the official publication of the All-China Journalists Association (ACJA), the government-led official organization for media workers in the country, profiled efforts in Zhang County to build a “county-level media convergence center” (县级融媒体中心), which it said would lend “strong public opinion support” to economic initiatives in the area and “effectively enhance the focus in guiding and serving the masses” – this second objective a clear nod to the policy of media control to maintain social and political stability.

A search for the keyword “county-level media convergence center” turns up tens of thousands of results in recent years, from both Party-run media and government agencies, with headlines like: “Building and Properly Using County-Level Media Convergence Centers.” How did these centers originate, and what are they all about?

Old Priorities, New Technologies

The CCP has long prioritized what it calls “propaganda and ideological work” (宣传思想工作), which is essentially about the Party’s dominance of media and culture as a means of ensuring that its values and priorities remain central in the lives of people at all levels of society. Since the 18th National Congress of the CCP in 2012, Xi Jinping has made many statements intended to direct the work of the press and the public opinion field more broadly. Since Xi’s first Work Conference on Propaganda and Ideology, held on August 19, 2013, media convergence has been an important component of the Party’s long-term media strategy, resulting in the introduction one year later of Guidance on the Promotion and Development of the Integration of Traditional Media and Emerging Media (关于推动传统媒体与新兴媒体融合发展的指导意见).

That formative document dealt chiefly with two aspects. The first was Xi’s insistence that traditional media and “emerging media” (digital platforms, video streaming et al) “develop as one” (一体发展). This was largely meant to ensure that Party-run media, which played a key role in “public opinion guidance,” setting the tone for media coverage favorable to the CCP, could modernize and not be left behind, which might imperil the Party’s agenda. Secondly, it was about moving converged media under the Party’s leadership to a more user-centered frame of thinking, recognizing that effective propaganda, and effective “guidance,” could only happen if new platforms could effectively “follow the laws of news dissemination and the development principles of emerging media.”

These principles were linked quite early on to Xi’s vision of strengthening China’s “international discourse power” (国际话语权), transforming the global “discourse system” (话语体系) and “telling China’s story well” (讲好中国故事). How could China speak loudly and with confidence in the 21st century if it did not do so through attractive and interactive platforms?

In the digital age, therefore, the task of “propaganda and ideological work” has become far more complex for the CCP, in the same way that media development generally has diversified and been innovated. Under the precondition of Party control of public opinion, the process of “media convergence” – which in other environments globally refers simply to the merging of different types of traditional mass media with the internet and interactive digital technologies – has become an important means by which the leadership asserts control over the creation and flow of information.

In 2014, He Dongping (何东平), the editor-in-chief of Guangming Daily, a paper published by the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department, wrote a commentary in which he outlined the concept of “integration,” or media convergence, as he announced the formation at his paper of a “media convergence center.”

He Dongping explained that convergence focused on integrating the content resources, editorial resources, distribution, product forms, communication channels, technical solutions and marketing strategies used by traditional media and new media in close collaboration – creating what he called a “unified platform for media content creation.”

Neatly contained within this new vision of the newsroom was the old idea of CCP-run media, like Guangming Daily, as the vanguard of “public opinion guidance,” ensuring that audiences (and the Party’s agenda) did not become lost in the chaotic world of digital information. “Facing a massive amount of new media information, readers can easily get lost in it, and the popularity of social media and apps has particularly aggravated this trend,” the editor wrote. “The converged media newspaper will be the navigator in the midst of the vastness of online information, providing the audience with a reading guide of the most important, essential and trustworthy [content].”

The Party and its re-made media structure were to play a crucial role in “navigating” (导航) through China’s digital transformation. The challenge, then, was to consolidate the Party’s leadership of this transformation at all levels.

Localizing Convergence

During a meeting on propaganda and ideology in August 2018, five years after his crucial first meeting, Xi Jinping included “the construction of county-level media convergence centers” (县级融媒体中心建设) in his proposal for the re-making of “propaganda and ideology work under the new situation,” this being a reference to digital transformation as well as wider geopolitical change. According to the read-out from the official Xinhua News Agency, Xi said “the government needs to solidly conduct the construction of county-level media convergence centers in order to better guide the masses and serve the masses.”

In fact, the construction of county-level media convergence centers had already begun across the country. In a report weeks ahead of the 2018 meeting on propaganda and ideology, the “National Broadcasting Think Tank” (国家广电智库), a WeChat public account under the National Radio and Television Administration, reported that broadcasting stations at the county-level nationwide had begun building media convergence centers in order to “promptly convey the voice of the Party and the government, and effectively guide local public opinion.”

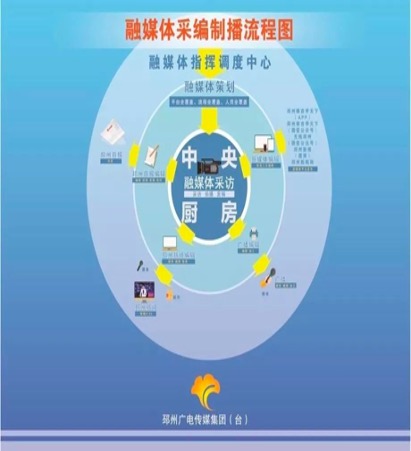

The article showcased Pizhou (邳州), a county-level city under the administration of Xuzhou (徐州), a major city in northwestern Jiangsu province, as an example of how local state-owned television stations could make the transition to media convergence using integrated media platforms – everything from dedicated mobile apps, online communities and social media channels, to traditional print and broadcast media. All of these activities could be conducted through a core department known as the “Central Kitchen” (中央厨房), where all interviews, video and audio recording, press releases and post-production could be integrated and distributed consistently.

In Pizhou, as in other counties across China, the “Central Kitchen” approach means consolidating the voice of the Party, and by extension its leadership at the local, “grassroots” (基层) level.

In the recent news from Gansu’s Zhang County, we can see the Party’s media convergence strategy continuing to play out, ensuring – at least in principle – that the all-important process of “public opinion guidance” is not just a top-down mandate, but can be fostered from the ground up.

Just like those fava beans.