Zhang Jialong, a reporter at Tencent Finance, photographs U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in Beijing in February 2014. Image by US Department of State available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.

When the All-China Journalists Association (ACJA) released its 2022 China Journalism Development Report (中国新闻事业发展报告) on May 16, detailing broader trends in the media sector, state media outlets noted that one of the key trends was the rapid pace of convergence – and the development of multimedia (多媒体) platforms, or “omnimedia” (全媒体), that combine text, sound, image, animation and other content forms.

In recent years, China’s leadership has repeatedly emphasized “convergence” as a priority in the re-making of the party-state media system, necessitating more creative deployment of propaganda and “public opinion guidance” through multimedia platforms.

But another key trend that was played down in much official coverage of the report was the dramatic impact digital transformation has had on the scale of journalism in the country. As coverage on some WeChat public accounts in recent days has noted, the ACJA report actually revealed – when compared with past reports – a net loss of fully one quarter of China’s licensed journalists over the past decade, with regional media leading the downward charge.

A Downsizing Profession

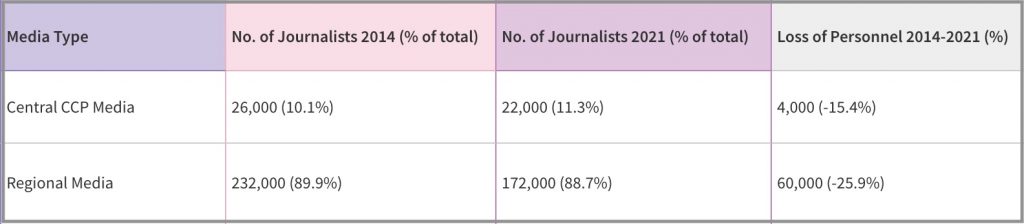

In the eight years from 2014 to 2021, the total number of media personnel with valid press cards (记者证) fell from 258,000 to 194,000, a decline of just under 25 percent. This translates to a total loss of 64,000 journalists across the country during that period.

Regional media have been hit hardest, with a loss of above one quarter of licensed journalists (25.9%). Central media, which include the likes of the People’s Daily, Xinhua News Agency and China Central Television, have lost just over 15 percent of licensed journalists.

Closures of both newspapers and radio and television outlets have no doubt exerted significant downward pressure on media employment. In 2014, there were 110,000 journalists employed at newspapers, according to that year’s ACJA report. By 2021, that number had dropped to just 78,000, meaning almost a 30 percent reduction in the journalist workforce (32,000 journalists) on the print side alone.

Radio and television outlets lost an equal number of licensed journalists, accounting for 21.6 percent of their 2014 press card carrying workforce of 148,000.

Press cards, or xinwen jizhezheng (新闻记者证), are required for media staff formally employed by news organizations and tasked under contract with news gathering activities, and are one of the crucial means by which the government seeks to place curbs on news gathering. The cards, which are issued only after reporters have received training in the mandates imposed by the Chinese Communist Party, are verified on an annual basis, and can be withdrawn for various reasons, including violations of political discipline.

Aging and Converging

Another clear trend in this year’s ACJA report, glossed over in official coverage of the numbers, is that licensed journalists under the age of 30 in China today number just 14,000 nationwide. This is down from 40,000 eight years ago, which means that one-third as many young journalists are licensed today than were less than a decade ago.

According to the report, licensed journalists under the age of 30 currently account for just 7.27 percent of total licensed journalists in China.

One important reason behind the sharp downward trend in the number of licensed journalists, particularly at the regional level, is the shuttering of traditional outlets, including many of the commercial metropolitan newspapers that once thrived in the heyday of print advertising a decade ago. The rapid development of digital media since the early 2000s has decimated the print advertising market.

Another likely reason is the very “convergence” trend cited more prominently in official coverage of the ACJA report last month. Under the centralized model advanced by the leadership, multimedia content is increasingly created not through local and regional news outlets, but rather through “media convergence centers” (融媒体中心) that package material for multiple platforms. The result of this trend is likely to be increasing centralization of the release of news across the country, with party-state controlled centers generating a greater proportion of content. And centralization means less demand for the press cards required for journalists to engage in news gathering.