DxChannel: Explanatory Journalism Through Video

Fang Kecheng

Lucia Shen

Fang Kecheng: Hi Lucia, it’s great to talk to you. DxChannel is a video brand I really enjoy. Can you first introduce yourself and your team’s background?

Lucia: First of all, I’d like to thank you for introducing us as a “brand” of video content, which is what I hoped to achieve, and not to just be an “uploader” (up主). [NOTE: This is a term for accounts that upload videos to sharing sites like Bilibili or YouTube.]

My name is Lucia. I’m a native Shanghainese. And I started DxChannel at the end of 2016. My undergraduate background is a bit complicated. I studied several cross-disciplines at first. One of them was called International Development Studies. My “track” was anthropology, but another background [in my studies] was economics. I think some training in visual anthropology can help you understand the method of using images to tell stories and to record some of the phenomena we see all around us.

Instead of working in the media industry after graduation, I first went to Deloitte, [the international professional services firm], where my job was to help companies conduct due diligence when acquiring other companies. In our early content, you can see some related methodologies at work . . . actually commercial due diligence methodologies, combined with some anthropological research methods.

After two years at Deloitte, I worked on impact investing, a somewhat idealistic field – in the small gap between investment and non-profit. It was a fund hoping to find companies that created both social and business value. We helped coach them from early-stage to late-stage development.

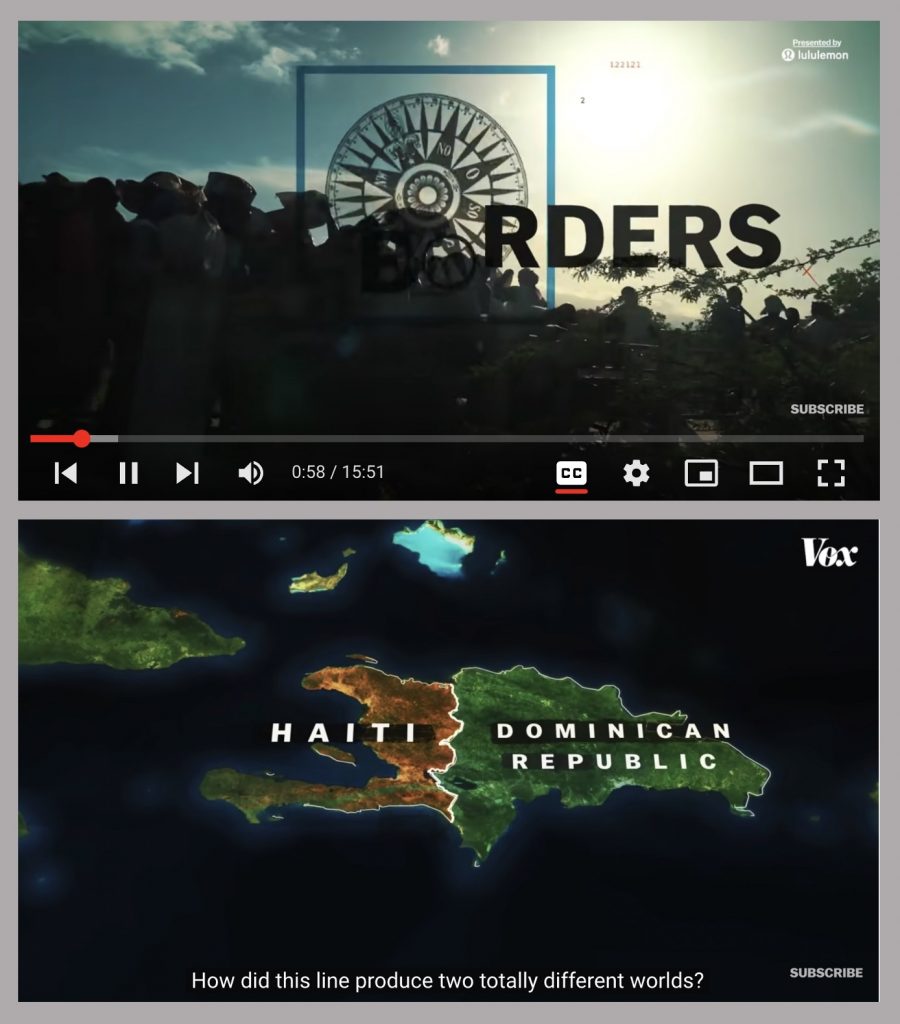

I ended up getting married and moved to the United States. I was a housewife for a year in the States and did some freelance work. I had a lot of free time, so I watched a lot of YouTube, and I especially liked the content from Vox and Vice. At that time, online video content in China was still relatively short and entertainment-oriented. I thought, “Wouldn’t it be possible to make Chinese content similar to that of Vox?” That’s when I tried to make the first video by myself.

Fang Kecheng: What was that first video about?

Lucia: At the time, spin classes were really trendy. Also, the business model was really fascinating. So I thought I would do a case study of its business methodology and make a video about that. Xu Xiaoping (徐小平), an investor, who happened to be in Boston at the time, saw the video. That was early 2016, the same time that Papi Tube was being developed [NOTE: Papi Tube is the short video multi-channel network company launched by video blogging sensation Papi Jiang].

I wondered if it would be possible to return to China for a summer internship with Papi Tube, just as a way to break into the industry. Xu Xiaoping said: “Why don’t you make your content? You already have a video.” I thought it might be possible, but I didn’t want to be featured by name. I didn’t want to become an influencer or an “uploader.” I wanted to create a video brand.

When I returned to China, Xu Xiaoping was really nice. He helped me promote our content and gain our first followers. From then on, we slowly built up a team.

Fang Kecheng: Did you start posting under DxChannel once you were back in China?

Lucia: I posted through my personal account. This actually explains why we are called DxChannel – [literally “Current Channel”]. My Weibo handle at the time was “Shen Dianxia” (沈殿霞), using my surname Shen, and because some people jokingly referred to me as “Dianxia.” But this is a really horrible ID because “Shen Dianxia” [Lydia Shum Din-ha] is actually an artist who has already died. So when I returned to China that spring, I felt like I couldn’t continue with the ID “Shen Dianxia.” I wanted to do it as a team, and I needed a brand. A good friend of mine pointed out that “Dianxia” is “DX,” which could stand for the word “dangxia” (当下), meaning “now” or “current.” The name really captured our theme, so we became DxChannel.

The first video we produced was about gentrification in Shanghai. Many of the streets we grew up on as kids are now full of beautiful cafes and pubs. But many of the original residents still live there. If you’ve been to Shanghai, you know the whole city is planned with a strong neighbourhood sensibility. You live, work, study, shop for groceries, play, and even go out at night all in one community. We noticed the peculiarity of Yongkang Road. The storefronts are all famous bars and coffee shops foreigners love to frequent. But the simple apartments upstairs are rented to local people, or just a handful of foreigners.

At that time, there had been a very well-known case of conflict between residents. Someone living in an upstairs apartment had poured boiling water out the window because they were too noisy downstairs.

We were fascinated by the question: what’s going on in our city? A friend of mine had opened a café on Yongkang Road and signed a two-year contract. But after just six months the government said it was taking the space back for renovation. I was puzzled by this, so I accompanied him to Yongkang Road to check things out for myself. First, I interviewed the manager of a downstairs store. When I got upstairs, though, things got a lot more interesting.

It turned out that while these popular downstairs businesses were thronged with customers, the people upstairs suffered from the constant noise, unable to sleep, from the garbage and so on. So the upstairs residents enjoyed none of the benefits of having the downstairs space rented out. This was an economic issue. So we delved into the issue of upstairs-downstairs along Yongkang Road, exploring why the government wanted to take it back.

We were fascinated by the question: what’s going on in our city?

In the beginning, I really couldn’t understand why was the government would break the contract and take [the shop space] back early? But it turned out there was a deeper reason behind it.

It was around eight or nine in the evening that we posted the video. We didn’t do any promotion. I woke up the next day to find the Weibo account was full of likes, and that the video had been shared by many other accounts. That video was posted to my personal account. The official launch of the DxChannel came later, on August 18, 2016.

Fang Kecheng: With the popularity of the video, did that give you the confidence to start your own business?

Lucia: It wasn’t so much about having the confidence to create a business. It was more the sense of accomplishment that came from doing the video. Knowing that I could tell stories in a way that resonated, or that people could be receptive to the videos.

Because the most significant breakthrough for online video in China in 2016 was Papi Jiang. You could see [from the success of her videos] that people needed an outlet. Other types of entertainment were actually really expensive at that time. Going to see a movie cost sixty to a hundred yuan. People spent a lot of time on the internet reading text-based content with graphics (图文内容). Video content met the demand a lot of people had to just let off steam and be entertained. The episode on Yongkang Road was a bit on the serious side, and it wasn’t short, about five or six minutes long – but still it got a lot of publicity. So I felt more confident that people would enjoy this sort of content.

When I first returned home [from the States], some of the feedback I received was that my perspective might be seen as too elitist. Just because I liked something didn’t mean other people would like it. But when that video came out, it convinced people that I could find an audience.

Fang Kecheng: In terms of style, could you say that that video on Yongkang Road was already in the DxChannel style? For example, in your videos having people at the center is really important, and everyone can follow along with the people in the video.

Lucia: Yes, I think it’s become an essential aspect of our “New Consumer” (新消费) column. It includes real-life visits. You couldn’t say it’s a journalist reporting, but it’s more like you’re following the person, documentary style, to find out what something is all about. We’ll also provide some historical background. And finally, we’ll use infographics to help explain the issue.

We’ve sharpened our skills in terms of content production, but I think the core is the same. We have three words: explore, explain, experiment. We throw some questions out there, and then experiment to seek answers.

Fang Kecheng: That’s interesting. It’s also a lot like Vox. But they seem to be more oriented toward the explanatory, and you guys feel more documentary in your approach.

Lucia: I think the essence of our stuff is more like the “Borders” series [at Vox] by Johnny Harris, because he really had a strong persona. He would add a lot of vlog elements, which you can also see in our early videos too.

One of the ways Vox inspired me is that it can actually be quite difficult to get a story across, and it’s hard to ask an interesting question. It’s all about what question to ask. And I think they do an excellent job of that.

Standardized Process, Personal Creative Touch

Fang Kecheng: Not being a media expert yourself, how did you go about building your team?

Lucia: I think there were three main stages. In the first stage, most of the people who joined me had the same background in social humanities. So relatively speaking, we would be different in our core content selection from those directly doing film. This helped us work out the [unique] nature of our material in the early stage. During the second stage, we were joined by friends who were journalists, directors, and screenwriters. They gradually helped us standardize a lot of things about our editorial process. By the third stage we had friends who had film backgrounds. They took us to the next level in terms of quality and visual style.

Our earliest team was a really amateur team. We all came from strange backgrounds. Our photographer at that time was an economics student, but he liked photography, so he learned on his own. Our screenwriter and director were undergraduates studying accounting. But they all had a fondness and enthusiasm for the content, and their own ideals.

Fang Kecheng: Do you have a production standard – for example, a procedure manual . . . or something like that?

Our earliest team was really a grassroots team. We all came from strange backgrounds.

Lucia: Yes. And there’s actually an evolutionary process involved there too. Our first-generation manual was actually a mind map. Very, very simple. But to this day we still use a lot of these core things. We divide our work into several stages including pre-production, filming, pre-processing of data, editing, archiving, content distribution, and project review.

In pre-production, we try to separate this into research and planning. For research, it’s all about what we can actually say about the topic. That is, we’ll have some basic questions to ask our production director. What makes it attractive to you? What questions do you want to return to with this video? What might the talking points be? What are your own ah-ha moments? We ask what our intention is in selecting the topic? And then we ask, then what? What is your takeaway once you know about this topic? In the planning stage, we work out our central theme and what we will experiment with in the story, for example.

For example, we had a video about call ducks. Call ducks are a type of domesticated duck that is kept as a pet. At that time, this was [chosen] because a celebrity had found that their pet duck went missing, and it turned out that someone had cooked it. He explained that the duck was actually very expensive and that it was his pet duck.

This led to a long discussion about the topic. In fact, many people keep ducks as pets. Our plan was to take an eating duck off to meet a pet call duck as a way of exploring this topic. We could make a side-by-side comparison and explore the question of why young people enjoy keeping such exotic pets – and talk about how we should view animals. This was the plan. And the research involved questions like: What is a call duck? Why is this such a popular topic? What determines their price? These were all talking points.

During the shooting, we tag what we think are the “money shots,” so that throughout the video we can make sure we have the catchiest shots possible.

Fang Kecheng: Did you make the manual yourself, or use references and learn from others?

Lucia: No, I just did it myself. Because I came from a similar production director background. As we complete more and more projects, different departments had other methods, so we started using [the productivity] software Notion. One of our company’s most significant assets is Notion know-how. We use it to manage all of our videos. We can see what pieces we have in the works, the status, who is responsible for them, and so on.

Also in the system are possible topics that we’ve brainstormed but that we haven’t started with yet. We’re just in the process of flirting with them, or maybe they are stuck.

Fang Kecheng: What do you mean by flirt?

Lucia: Well, for example [the topic of] industrial hemp. We think this is a really good topic. So why are we still flirting with it? Because it’s possible it’s something we won’t be able to upload [given content restrictions]. In fact, we had already settled on an industrial hemp farm in Heilongjiang, and we did interviews in May. The planting time was in October. But that September a ban came down saying that industrial hemp could not be used in cosmetics products [where it is typically included as a moisturizing agent].

So that was the end of that. There was no way we could continue with the topic from that point.

Fang Kecheng: What happens once you’ve chosen a topic?

Lucia: Once we’ve settled on a topic, we go and find [the necessary] people. We have some very useful toolboxes on our side now. For example, a list of experts. These are people we’ve interviewed before – people like you, Kecheng. It’s possible your name is in there too.

After that we make the outline. In the outline we include the planning outline, the pre-script, the site outline, and the editing script. After that we have a timeline for every video. These have all been carefully incorporated into the work of the production director, helping them achieve each step and create a standardized product.

Finally, there’s the review stage. The review is extremely important. It’s mainly about scoring [the work] with our peers, determining what we can learn from and take away in the hope of improving what we do. The points we like most, the points we like the least, we all provide feedback. The framework of our feedback is something we learned from Netflix. There is a book from Netflix, and inside it talks about this thing they do called “stop, keep, do more.” “Stop” is about the things you want those involved [in production] to refrain from doing [in the future]; “Keep” is about continuing [to do the things that are working]; and “do more” is about those things that you could have more of. That’s the kind of feedback we give one another. After that we look at the feedback data. And finally, I have a one-on-one session with the production director.

Fang Kecheng: Considering this, I think it’s understandable why your videos have come to have such a professional look. The preparation is a very professional process. Does this have anything to do with your previous methodologies from working at Deloitte, or did you re-discover them yourself?

Lucia: I think it’s a little bit of both. For example, why do we use Notion? I think it’s more like a wiki for the company. A lot of things have to be used all the time. For example, if everybody wants to use a portrait template, why don’t I just create one so everyone can download and use it with a single click?

Fang Kecheng: Standardization is essential. But interesting topics are determined by human creativity and not by the tools themselves. I wonder how you go about finding the most exciting topics in the selection process?

Lucia: The starting point for choosing any topic is that it must be attractive to the production director. If they’re not interested in the subject it’s not going to be good.

Fang Kecheng: Then you need to recruit interesting people first, right? Interesting people bring interesting topics.

Lucia: Our number one requirement in recruiting is not experience but curiosity. I think curious people are usually good at observing and asking questions. They look at the world around them with questions.

The second element of topic selection is the role of the planner. What the planner does is summarize every week at a meeting what has been happening that week and what things they’ve found particularly interesting, pushing ideas to the program directors. If the PDs find something interesting, the planner will explore the topic further.

At the same time we hold topic selection meetings where the PDs can also submit topics for consideration.

Fang Kecheng: Have there been topics the producers are interested in but you’ve shot down?

Lucia: Yes. For example, if a PD submitted an LGBTQ question, I would have shot it down due to consideration of the political environment. When deciding whether to broach a question or not, we have to consider if and why the audience will click on it will be open to it. Secondly, I have to know if we will actually be able to shoot something [given content or filming restrictions]. And finally, we have to consider whether we’ll be able to broadcast it afterward.

In these kinds of cases, you are bound to fall into the challenge or trap of self-censorship. Usually, a lot of personal discretion is involved. Whether you’re the chief editor or the content director, you have to judge whether the topic is in line with our current direction. For example, the subject of surrogacy is very sensitive, and there is a possibility that such content will be taken down. We need to try not to block out or disregard the topic, but at the same time find a balance, an angle to get it online. We’ll do a lot of preliminary work and ask the [distribution] platform whether something will be permitted online.

In these kinds of cases, you are bound to fall into the challenge or trap of self-censorship.

Back to LGBTQ, in 2017 we started doing topics around drag queens, and that was allowed. But by 2018 they were taken down by the domestic platforms. So it’s already the case that the winds are shifting that way. If we can’t guarantee operationally that something can stay online, we may choose not to make it – because all of our videos require a certain level of resources. You have to decide if something is worth it or not.

Who is Our Generation Anyway?

Fang Kecheng: How would you define the positioning of your video series?

Lucia: I think the core of the content is answering a single question: Who are we really as a generation? It is a curiosity about this one group. It’s just that each category has a different angle. The “New Consumer” section, for example, is about exploring who we are through the items we consume. For example, why do we have ducks as pets? What does it say about our generation? “This is Us” (我们这一天) explores our generation through our professions: What do we choose to do for work? What does this say about our generation?

“What If?” (我有一个想法) is a relatively new section, which is about exploring something curious. Previously, there were a lot of topics we have to leave aside because they didn’t fit in “New Consumer” or “This is Us.” But our production directors really wanted to do them, so that’s why we created this new section.

Fang Kecheng: So when you talk about “our generation,” what years are you talking about?

Lucia: I don’t have a particular year date. But usually the “This is Us” professionals are under 35 years old.

Fang Kecheng: You said earlier that the most essential point to think about when choosing a topic is why the audience would want to watch it. Can you predict how many people will watch a video now? Are there times when the numbers surprised you? Were there videos you thought would be popular but weren’t, and other videos that you thought wouldn’t be but ended up being hits? Do you have a good sense, in other words, of whether a video will go viral?

Lucia: Usually when I look at the first 48 hours of data I can get an idea of what it will probably end up being.

Fang Kecheng: It is not possible to not look at the data at all?

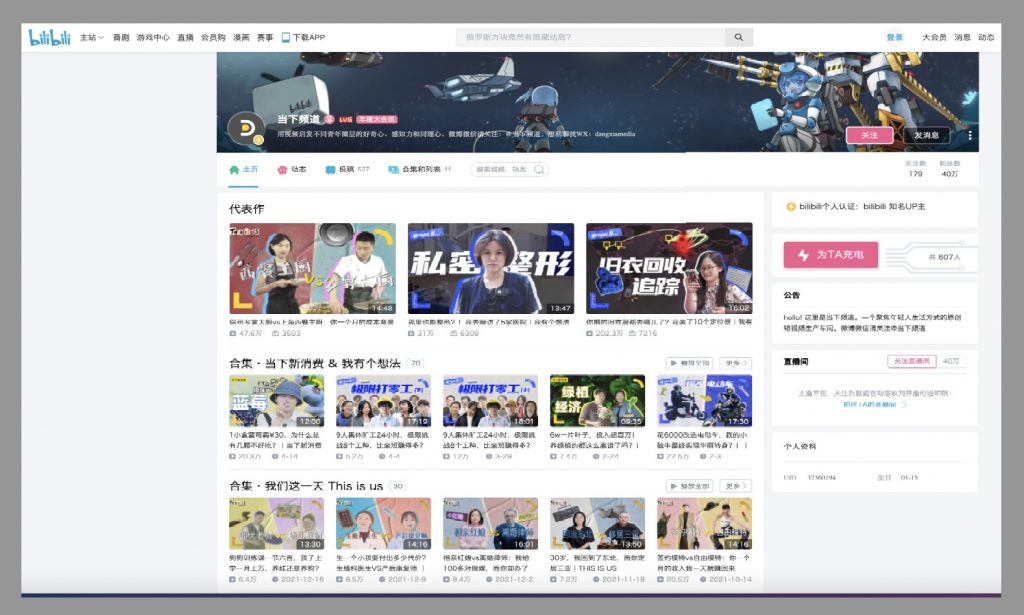

Lucia: No, it isn’t possible. Because different platforms have different recommendation algorithm logic, and whether and how our videos get recommended by the algorithm matters a lot. So I usually look at the engagement rate in the first 48 hours, that way, I can estimate its peak views on Bilibili. It’s relatively accurate.

When we ask “Why should viewers watch?” it’s not about numbers of viewers, but about what value we are adding to the audience. Then it’s important to think about the topics that viewers care about. There may be something that we believe the audience should know. For example, we were doing a piece about how algorithms are affecting people’s lives. I believe this is a fascinating topic to explore. But if we make the title, “How algorithms affect us,” I don’t think most people will care. On the other hand, if we change it to “Can we find true love on dating apps?” the question suddenly becomes sexy. Everyone feels this is more relatable and more relevant to young people’s lives.

But what we are really talking about is how the algorithm matches you with the information you see. When you choose a topic, this is the logic behind the question of why the audience would want to click on it.

Fast Growth is Hard to Come By

Fang Kecheng: I followed you guys very early on. You probably had less than 100,000 followers on Bilibili at the time. The content quality was already quite high. I remember people left comments saying: This is so well done, how is this not viral yet? I thought at the time that you guys should have at least a million followers.

Lucia: Now, both platforms add up to one million followers.

Fang Kecheng: That’s great, but you deserve more. When you didn’t have a lot of followers, did you ever wonder if the algorithms gave enough recognition to such well-produced content?

Lucia: I think it’s okay for me, but for some of our PDs, getting a good reaction is the main motivation for them to make content. The stats may directly indicate if the video is good or not. But from a business point of view, I don’t have a lot of traffic anxiety. Because our primary way of earning profits is not through views. Instead, we do commercial subscription content, and that supports our editorial content. So even in the beginning, we were able to have a dependable level of production value, and we were able to charge a reasonable price.

Why are we doing content branding? Because brand power should be production value multiplied by distribution value. What you eventually want to do with self-media (自媒体) is solid content, to be able to tell a story that can be recognized by the brand and also have distribution value. Although we started with a small distribution value, the production value was OK, so it was fine. Of course, it’s an added benefit if we are able to improve our distribution value.

Our business model now is actually half and half. Almost half of our revenue comes from helping other brands produce content, being an OEM content factory. The other half of our revenue comes from commercial partnerships with our own [editorial] content.

What you eventually want to do with self-media is solid content, to be able to tell a story that can be recognized by the brand and also have distribution value.

Fang Kecheng: Did you have outside investment initially, or did you use your own money?

Lucia: I used my own. I had a certain amount of savings and few people to support at the time. Actually, it was me, a PD, a photographer, and a couple of interns.

Fang Kecheng: I’m sure it wasn’t easy at the beginning, but the lack of pressure from investors should have given you more freedom to explore in terms of content.

Lucia: Yes, you’re right.

Fang Kecheng: Can you tell us about the makeup of the current team?

Lucia: We divide our team into “front office” (前台), “middle office” (中台), and “back office” (后台). Our production directors are the front office. PDs are responsible for a project from beginning to end, just like project managers. We currently have six PDs. People in the middle office work on several different projects simultaneously, but each person is concentrated on one particular function of the work. So it’s a T-shaped structure. The PDs are the horizontal bar of the T, and the middle office forms the vertical bar in the middle of the T. We have six people in the middle office, including production assistants, the camera crew, and animation artists. The back office is all of the work that we outsource.

Fang Kecheng: It seems that no one is dedicated to doing commercial collaborative content. So the PDs do the editorial content and also the commercial content?

Lucia: Yes. It depends on who’s interested in what. Maybe one person gets tired of doing editorial content after a while and switches over to commercial content. Commercial content pays more money, but it has to serve a particular purpose.

Fang Kecheng: Speaking of the business model, do you have a good sense of how much each episode costs?

Lucia: I can’t say an exact number, but I can give you an idea. We usually calculate by the hour, following industry standards. A video usually requires a writer-director for two months, plus planning for two weeks, a producer for a week, and two cameras for a week. It’s about those hours. If you know the current industry salaries, you can calculate the cost of one of our videos.

Fang Kecheng: Are there any other companies with business models similar to yours?

Lucia: I have come across the newsgroup ArrowFactory Doc (箭厂), which is similar to ours. I don’t think our business model is new. For example, Vox has its own Vox Media content and also has a Vox creator studio.

Fang Kecheng: Your example is an encouragement to people – that making quality content and making money are not contradictory.

Lucia: I think we should be considering how we can make money on our own. Because my hope is that the business is viable over the long term. So it’s crucial to find ways to build cash flow from the beginning. In the content industry, each piece is unique, and I think it’s difficult to grow fast.

That’s why there are so many content brands that eventually go the e-commerce route. In e-commerce, you can sell one SKU, or distinct item for sale, to a thousand or maybe ten thousand people. But in the case of content, consumption ends after one viewing. The audience generally will not return to the same piece again. But personally I don’t want to go down the e-commerce path.

Short Videos Won’t Kill Long Videos

Fang Kecheng: Let’s talk for a bit about audience feedback. This should be an interesting topic. I have seen some nasty comments, even trolls, in the comments section of your videos. This is the norm on the internet now. How much do you care about audience feedback? You mentioned earlier that you have input from within the team, and from you personally. But I don’t seem to see feedback from the audience.

Lucia: In the early days, especially during the first year or two, I read almost every comment, every pop-up, because those were really our core fans, and I cared very, very much about what they had to say about us. If I see the IDs of old fans pop up, I will personally reply to them and express my gratitude – because they’ve been with us since we started growing. I care a lot about what they think.

At this stage, the feedback I pay attention to is the numbers. For example, what is the ratio of comment pop-ups during playtime? This can tell us how the topic is trending. Secondly, we look at the video completion rate, which is the indicator we care more about: how many people have watched a video from beginning to end.

As for some of the voices in the comments section, I think it’s best to turn a blind eye. When you get a lot of views, there are bound to be some mixed opinions. Sometimes it’s interesting to see the audience discussing a topic. And if I can see that it’s constructive, I listen and comment.

Fang Kecheng: Do you think this is because you guys have gradually broken out of your own circle? Or is it that the climate of online public opinion is worse now than it was three or four years ago?

Lucia: I think it’s both. The most important thing we look at is feedback comments on Bilibili. B Site as a platform is also breaking out itself. Originally, it was mostly about ACG [animation, comics and games], but it has since attracted a more high-knowledge crowd, and its user base is contracting.

As for the public opinion climate, I think you can say on the one hand that it’s more “democratic,” meaning the threshold for access is lower. On the other hand, everyone needs to voice their opinion in shortened formats. Most of our friends now are accustomed to expressing themselves on Weibo, so anywhere from ten to a hundred characters. So it’s just about tossing out conclusions, views, or prejudices. You’re not able to articulate well why you have a certain point of view.

I think it’s definitely because of changes in the social media landscape, which can cause responses to be more one-sided or biased. Another factor is the echo chamber. Algorithms make it easier to see more readily the content you agree with. Then, when you see something particularly different from what you’ve seen before, you tend to voice your responses in the extreme.

Fang Kecheng: One problem we have with viewing traffic data now is that if we just look at the numbers, all the numbers are the same. For each like, you can give one, I can give one, everyone can give one, but each like represents something different, even though it’s displayed in the data as a single indicator. So this is one limitation of metrics . . . . But speaking of audience feedback, one of the series you haven’t talked about is the vlog series, which is a sort of behind-the-scenes look [at DxChannel]. Is this about seeking more engagement with the audience?

Algorithms make it easier to see more readily the content you agree with. Then, when you see something particularly different from what you’ve seen before, you tend to voice your responses in the extreme.

Lucia: That’s right. I think for the audience, the vlog is actually about operational content. By operational content I mean greater transparency – because when we’re doing many of our topics we’re making these industries more transparent. For example, we’ll go and look at the upstream processes of a certain industry, exploring what it’s like behind your consumption. As a content brand, we’d also like to let people know how we go about making our content, who we are [as a brand], and who we are as individuals.

So we basically divide our vlog into two sections. The first is how we do our content, and it’s a “how to.” The other section shows [the audience] what our daily lives are like, seeing who we are. It’s just as you said, in the hope that we can have more interaction with our viewers.

Fang Kecheng: Perhaps in the future the vlog series can allow viewers to visit you and chat with you.

Lucia: Exactly. I’ve even given some thought before to bringing other content creators in for discussions.

Fang Kecheng: You mentioned earlier that when you formed your team the video industry in China wasn’t so developed, and that the most popular content was stuff like that of Papi Jiang. In your view, how have things developed in the online video industry over the past few years? What is the industry like now? And as an observer of developments in the United States, do you see any gap still there?

Lucia: First off, about domestic developments, I think things are more diverse now, and more professionalized. Early on user-generated content (UGC), stuff that users filmed themselves and uploaded, really dominated. By 2019 and 2020, there was more professional user-generated content (PUGC), stuff that like ours falls somewhere between completely wild personal content and professional media output. A lot of the more mature content production you see now is actually done with the team approach (团队的方式), which ensures continued output.

Secondly, I think back in 2016 content formats, or you could say the value content offered to viewers, was more about helping users kill time (帮助用户杀时间). But now more and more content is about helping users save time. For example, tutorials, paid instructional [content], explanation of the news and so on. It’s more and more diverse.

You can see the diversity too in who is participating. Back in 2016, friends around me, like those in business school, were also saying they were interested in doing something. But they also felt that this wasn’t a real form of employment. But when you look at it now, many people started out as professionals in other industries – for example, as psychologists, securities analysts, even doctors. Many of these professionals have other industry backgrounds, but now use video as a medium to share their “know how.”

Before videos were just videos. But now videos are another medium of dissemination, and whether or not you have a media background has faded in importance.

As to comparisons between China and the United States, one really big difference is distribution (分发). The US is still rather centralized. For medium to longer videos it’s YouTube. For short videos it’s TikTok or Instagram TV (IGTV), [now known as Instagram Video]. In China when we upload a video it’s to Bilibili, Weibo, Weixin, Xiaohongshu (小红书) and a whole variety of platforms, and this means the management of content is very different. The audiences on different platforms have different demands of videos and different habits. What is the advantage of this? It’s that we have more diverse ways to monetize. Actually, the ways of monetizing are very different on different platforms.

Before videos were just videos. But now videos are another medium of dissemination, and whether or not you have a media background has faded in importance.

Fang Kecheng: How do you see the development of short videos?

Lucia: The viewing threshold for short videos is a lot lower, but that’s not to say that they will push aside longer videos, because they are very different in terms of consumption and meet different needs. You can see that YouTube is also doing shorts. The same producer may be doing two different sets of content. But I think it has the advantage of bringing some people in. They may slowly start to watch longer videos.

Fang Kecheng: My last question. Do you have any advice for people who want to enter the video industry?

Lucia: Just do it.

Fang Kecheng: Is it that easy?

Lucia: Really, it is. Because now there is such a low threshold for content production. And to be honest, as long as you have an idea, you can find very cheap tools to help you achieve it. Like how we used to do our content. You may need a team of professional writers, directors, and equipment. But now an iPhone works for filming and editing, and then you can just upload it. I think it’s more about not being afraid, having an idea, and grabbing it. Try it first and see how it looks.

And then make sure to rest. I think it is easy to burn out. Or you could say that our generation burns out easily. When you’re in the content industry you are doing a lot of output, and in fact to output more effectively you need a lot of time to do input, and to let things gather and settle.

Translation by Sara Yurich.

CHECK OUT CONTENT FROM DxCHANNEL:

DxChannel Team Member Explores Her Father’s Efforts to Be an Online Product Rep

Fang Kecheng