Unpacking the Booming Racist Video Industry in China

Joyce Chan

Runako Celina

Joyce Chan: First, I wanted to thank you for producing the insightful documentary “Racism for Sale” on the BBC. I know it generated attention and spurred discussions of racism in the Chinese media as well as in the non-Chinese speaking world. But these types of racist videos aren’t exactly a new phenomenon on the Chinese internet. Can you tell us why you decided to pursue this topic now?

Runako Celina: Thank you very much for saying that. It means a lot. I was living in Beijing at the time the video [that opens the documentary] came out, and I’d seen these videos for years. The industry has existed since 2015. And so, you know, every time I received videos emerging from the industry I was disturbed. Many people [angered by the videos] were Africans, and many Chinese as well felt uncomfortable every time they saw this content. But no one really knew what was going on behind the scenes.

I started to observe a gradual kind of progression in the types of content being produced. This industry exists on social media and social media thrives off of innovation — you do one thing and then you get clicks, and it’s like a drug and you want to get more follows and more clicks and more likes, and more sales in this case, until you push boundaries. You try to innovate and create something more, and so I gradually started to observe that this was happening within this industry as well.

It might have started off quite innocently in terms of the content of the videos, with greetings or celebration-related content. But eventually, we started to see the content getting worse.

In 2019, I remember seeing a video on the platform that I cofounded, Black Livity China. I think it was from 2019 or 2018 [and it showed] children speaking about a football team in China. They were made to chant foul language in Mandarin to describe the football team. Although they weren’t insulting themselves, these children quite clearly had no idea what they were saying. That to me represented this gradual progression. And so in 2020, this video emerges online [in which children were asked to insult themselves].

Joyce Chan: This is the video that starts off “Racism for Sale.” Certainly, it’s shocking for viewers, the children using a deeply hurtful racial slur in Chinese. As you explain in your documentary, the word the children are using, “Heigui,” could be translated as “black devil,” but is really equivalent to the N-word.

Runako Celina: I don’t want to say [it was a case of] enough is enough. Because to me, the industry shouldn’t have started in the first place, and this content should never have surfaced. But it was kind of enough is enough. You feel like this is just hideous. At this point, something’s got to give.

So I decided in December 2020, the same year the video came out, that I wanted to investigate it. It’s just taken this long for us to get things together in a way that we needed to and to gather a lot of evidence to put it out now. The whole process took one and a half years to complete. It’s a 50-minute documentary. It is impossible to include everything that we found out in the process of that investigation, but some of the wrongdoing and some things that Malawian media have even picked up on since are just hideous. So, it’s a drop in the ocean.

Joyce Chan: I assume there must have been quite a few of these videos around on the internet. What was your process for selecting this one particular video to hone in on?

Runako Celina: The investigation’s main focus — what we try and answer and investigate — is who made this video. Where was it made? Why? It starts very much focusing on this one video. Especially on my personal journey of investigating this, as you go into one video, you realize that you fall into a cesspit of content online that is far beyond just a 30-second clip. Now that clip does represent some of the most heinous types of content that we see in this industry. But it’s a drop in the ocean, as I said. So although the investigation centers around those questions to do with this one video, it does shine a light on this wider topic of anti-blackness and racist content on Chinese social media — mostly as part of this industry. But it opens this idea to “Hey, this industry wouldn’t have existed unless this content and content like it was attractive to an audience for a reason.”

Profit is what pushes an industry like this. We hear Lu Ke, the man behind the camera, tell us himself about how profitable it is and why he’s filming these videos. Obviously, he denies filming the racist videos —that’s important to state — but he gives us examples of how profitable it is. And so to me it’s also about raising the wider issue of anti-blackness that makes content like this have a market in the first place.

Joyce Chan: You mentioned that the industry started existing in 2015. Could you clarify what you mean by the “industry”? Do you mean the production of videos that exploit African children?

Profit is what pushes an industry like this.

Runako Celina: When I say the industry I’m referring to [what’s been called in Chinese] the “blessing video industry” (祝福视频行业). It’s very hard to directly translate it. In the few places where these content creators have tried to use English, they have translated it as “blessing videos” or “greeting videos.” [NOTE: In Chinese media coverage, these have also been referred to as “African blessing videos” (非洲祝福视频).]

There are different terms for it. I’m referring to a very specific format in which groups of people huddle around a blackboard dressed in costume saying words in Chinese with someone else off camera. That video format is what powers this industry. I wouldn’t like to guess when racist content started appearing on China’s internet. But when I say 2015, I’m just speaking specifically about this particular industry.

Joyce Chan: Moving on, I’d like to hear your perspective on the approach of the Chinese media and policies towards the portrayal of African countries and China-Africa relations. The official media narrative tends to focus on economics and practical issues like trade while remaining ambiguous on issues of racism, neo-colonialism, and social issues in Africa. How do you view the picture of Africa in the Chinese media?

Runako Celina: It’s difficult for me to answer directly about governance and policies. But the thing that I would say is that we raised questions in the film about why this content was allowed to be on the internet for so long. This industry doesn’t have a market or a way to market itself without social media, and so I think there’s a massive question mark raised by the film — and by people who have seen the film. Everyone’s question is: Why is this content out there?

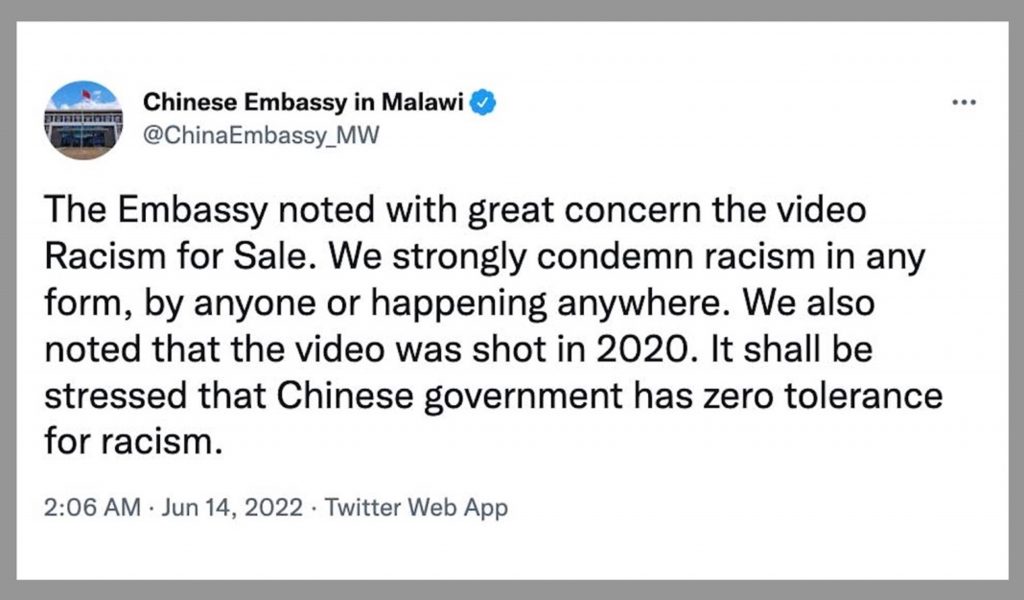

I can’t answer what the government’s doing and what their intentions might be. But I also recognize that it’s very questionable that this content has been allowed to exist online for such a long time. The thing that’s been promising to see since the film’s release is the reaction from the Chinese Embassy in Malawi, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), and Wu Peng [head of the Department of African Affairs at MOFA]. They have come out and said this content should not be allowed. It is interesting because the statement from the Chinese Embassy in Malawi suggested they might have been aware of content like this for some time.

I wrote an article off the back of this film detailing more of my thoughts about the film and the process of investigating it. One of the things that I tried to emphasize was that it’s interesting that this content continues to find its way online on an internet as heavily censored as China’s. We’ve seen instances [in the past] when there is an attempt to shut down conversations on certain topics, and it’s done very thoroughly. So, I leave it to the audience to decide what they would make of the fact that these videos still somehow find their way online.

Joyce Chan: How does this reflect, do you think, on the Africa-China relationship?

Runako Celina: In the dialogue around Africa-China relations, the human element is often removed, I find. By the human element, I mean the people-to-people relations, and what the influx of Africans to China and the influx of Chinese to Africa means. There are multiple relationships rather than a single relationship.

Sometimes we tend to think of China as a block and Africa as a block, but Lu Ke [the Chinese video-maker featured in the BBC documentary] is not a representative of the government. He’s an individual who came as a migrant worker. But even though these are an individual’s actions, they have implications for the wider relationship, and I think that speaks to this question mark about responsibility and whose responsibility it is to tackle the issues that we see in the film — such as the racist attitudes that make content like this have appeal [in China].

In the dialogue around Africa-China relations, the human element is often removed.

One of the things that lots of people have been saying is this question of education beyond just censorship, beyond just taking these videos down. Racism can manifest in other ways, and if the root causes of it aren’t dealt with . . . What’s happening on that level? How do we stop people from having those attitudes before they reach an African village or a Malawian village and interact with actual Africans?

And the same should go vice versa. It’s just that question of what is actually being done practically. Like I said, after the film came out, we heard an instant statement from Wu Peng saying this is unacceptable, and we are cracking down on content like this. So, to me right now it’s about watching and waiting to see what happens next what comes next on the back of these statements.

Joyce Chan: Do you see these Chinese official statements against racist videos, then, as political blanket statements to prevent backlash from Malawian or other African governments?

Runako Celina: I think, firstly, that the fact these statements are coming is promising. It’s not every project of this kind that receives a more open reaction, more open than the one we’ve had. The statement from the Chinese Embassy in Malawi [through Twitter] basically said this is wrong, but added that “the video was shot in 2020.” You can see the responses [to that statement] that they were basically torn apart for playing the incident down as something in the past. Some things speak for themselves, right? But what I would say is that it’s very promising to see that reactions happened anyway, reactions that overall were not that defensive. But it’s a question of seeing what happens now.

There was a really good article written as a follow-up to this by Viola Zhou at Rest of the World. It looked into the wider question of these markets online, beyond just the blackboard-holding videos. She looked at the wider exploitation of Africans on Chinese social media. One of the things she highlighted was this question of action. Basically, she spoke to lots of content creators in this industry. They had already noticed that social media platforms, including Kuaishou and Douyin [the domestic version of TikTok], had started censoring searches for the term “Africa” (非洲). So perhaps that would suggest that things are being done. Whether they are the right things, or whether they are going to make a difference — that remains to be seen. But it’s an example of the reactions to our film beyond just statements.

Joyce Chan: So, this new keyword censorship was a consequence, you think, of the information revealed in your documentary?

Runako Celina: Yes, exactly. Beyond the government’s reaction and response, one of the things we have seen as well is that content creators themselves have started taking down this content, and have started to leave [Africa] as well. One of the most prolific content creators filming [African] children, Lu Ke, has obviously left. Then there was a second guy, also in Malawi, who also fled the country after the film came out. So yes, the film is having an impact.

Joyce Chan: You are saying that content creators have been physically moving from the country to escape from prosecution?

Runako Celina: I think beyond the risk of prosecution alone, it is the backlash or the risk [for content creators] of being associated with what has happened. One of the things we tried to do was to highlight that this is not just a Malawian problem. It’s not just a problem that happened in this one village. In the earlier parts of the film, we highlight a map of the African continent and we highlight several countries [where operations are happening]. I’ve since found other countries that host operations like this, including some featuring children. It highlights the wider trend across the continent, so it’s been great to see this conversation taken seriously.

Joyce Chan: So these video operations are an Africa-wide phenomenon, not limited to Malawi.

Runako Celina: Absolutely, it’s a broader issue not limited to Malawi. Throughout the film, we see quite continuously that the word used [to refer to the children and others in the videos] is never “Malawian” (马拉维人). It’s always “black people” (黑人). The term that is used is always “black people,” no matter what country they are from. It’s a much broader issue. The attitude is toward “them,” rather than toward people from a certain country or a certain village.

Joyce Chan: Would you say this attitude is representative of Chinese media as a whole or just social media?

Runako Celina: Yes, there are these sweeping blanket statements often used about African-ness and blackness, which are found also on Chinese social media. They represent this ignorance that exists and, more than ignorance, they often represent this racist idea that exists — of “these people” with “these set qualities,” and the associations are normally negative.

Beyond the government’s reaction and response, one of the things we have seen as well is that content creators themselves have started taking down this content.

We see this manifest perfectly in the film with things that are said in the undercover footage. For example, the things Lu Ke says about black people are hideous. But if I’m honest, I wasn’t surprised to hear them. I was kind of surprised that he just said them off the cuff, but I wasn’t surprised that he had those opinions at all.

I think one of the things that stands out for me is how we described him as an outcast. And he really was. He wasn’t well integrated into the Chinese diaspora in Malawi. But what made him an outcast wasn’t actually his racist views. Those racist views are very common. He was an outcast more because of his class and background, so I took that as kind of a microcosm of the fact that these views and opinions about black people are so widespread and often go unchallenged online.

In a podcast episode, Wode Maya, a Ghanaian YouTuber who has been vocal about these issues [of Chinese racism] from the very beginning, said that speaking as a black person, if you were to go online in China and understand what is being said about black people, you probably wouldn’t want to go to China. I think that’s a good way to sum it up, because some of the things [online] are hideous, especially to someone who can understand. This industry is just one example.

Joyce Chan: As you said before, it’s only the tip of the iceberg. But do you think attitudes on social media have changed at all since the emergence of these exploitative videos, considering the rapid growth of China’s social media culture? Has the notion of racism seeped into the public consciousness?

Runako Celina: I think there’s an awfully long way to go. I think the problem is that racist online content has been allowed on the internet for so long without any censorship, in my opinion. When that happens, the idea then becomes that this is tolerable and that we can say whatever we want about this group of people, and it means nothing. One of my greatest fears, if I’m honest, living in China and seeing some of the things said — the vitriol about Africans in Guangzhou and about African students getting scholarships in China and so on — is that online violence only stays online for so long.

Like most forms of online hate, things only stay online for so long. So how long will it take for that to spill into real life? It used to be a great fear of mine that it would end in an African getting attacked, a death, or something like that. I know people who have been shouted at and discriminated against in the street [in China] in ways that definitely have to do with their race. So, it’s problematic not only because it’s horrible to see, but because it has a real-life impact.

The image of African-ness and Blackness that is allowed to exist in the online imagination on Weibo and other platforms plays into it too. Some accounts search for people in interracial relationships, like a Chinese woman with an African partner, or pictures of people in partnerships like that, and they post their pictures on Weibo inviting people to comment on them and post hate about them. I have also seen African families who upload pictures onto Douyin, and the comments fill up with gorilla emojis and comments like, “Leave China,” things like that. My fear is that the hate only stays online for so long.

The impact of content like this is large and wide-ranging. To answer your question in a nutshell, I don’t think it’s changing. I don’t think it’s getting better.

Joyce Chan: I would have thought coverage of racism towards Africans in Guangzhou during the Covid-19 pandemic might have had some impact on people’s perceptions and attitudes. But that doesn’t seem to be the case.

Runako Celina: Someone might argue that that’s because it’s not being followed up on beyond that. If these instances happen and it invites widespread media condemnation across the world as the events in Guangzhou did, what should the response be on side of the authorities? What is happening then to tackle the issues that led to people using the instances to express such hate and vitriol towards Africans online? Were there any consequences for these actions? If not, then these things are going to continue.

Racism is not a Chinese invention. You see the same things here in the UK. Whenever something bad happens in the UK, it’s the most vulnerable groups that get the blame. If we follow the example of the UK, those views often go unchallenged because it means that the government can just continue and do what they want essentially, because there is a scapegoat. Naturally, people are more emboldened online to say things they wouldn’t offline. But the impact of the hate that can come out online is felt offline.

Racism is not a Chinese invention. You see the same things here in the UK.

Joyce Chan: How do you see the existing guidelines or regulations on racist and hate speech in Chinese online media? Is lack of enforcement part of the problem?

Runako: This wasn’t a part of our investigation. We focused specifically on the actions of the individuals and tried to hold them accountable. We didn’t try and seek accountability from the platforms because that conversation would start naturally after the film came out anyway, so I can’t say that I have tried to investigate whether or not there are policies in place.

For me, it comes back to the fact that, whether or not policies are in place, I have personally seen things censored in a matter of seconds when the will is there. But if there were efforts to censor racism on Chinese social media, then clearly these are not working. Content like this still constantly appears online.

But I will note one of the discussions I noted in China following the release of the film. I spent the first day after the film came out on WeChat to see what my old professors and classmates might be saying and how the reaction might be different from how Western audiences reacted to the film. One of the things I noticed was that some Chinese academics specializing in African Studies said they had been vocal for years about content like this online and how it damaged the image of African-ness and Blackness online. They said they had had conversations with app companies and social media companies letting them know this needed to be taken seriously, but there was never any serious attempt to deal with the situation. So that’s why all these years later . . . Remember, the industry we focus on started in 2015, so that’s seven years . . . That’s why all these years later this content still exists.

Joyce Chan: Just to clarify, you mean there have been attempts by individuals in China to speak out against such racist content?

Runako Celina: On lots of different sides, yes. Africans have been very vocal and Wode Maya is an example. But it’s really important to say as well that academics in China have been rallying against it for a long time. Obviously, the way that they fight is different. It might be through closed-door conversations with app companies, as I said.

Joyce Chan: I think there is a representation issue as well. Opinions from people of African descent or Black people would perhaps bear more significance than Chinese voices and give more agency to Black African voices when it comes to racism issues. Do you think so?

Runako Celina: Yeah, I think so. I’ve realized there are certain things I would never be able to achieve, or that there are limitations on what I can do as a non-native. Even if I speak Chinese, I’m still non-native and certain doors are closed to me. That’s just the reality. It’s not something I’m bitter about, just something I’m aware of. There are limitations on how far I can take certain discussions.

Everyone works on their own different turf. For Africans ourselves, it’s very nice to see this is an African-led initiative to tackle an issue that so many of us have felt and been pained by for such a long time. For the academics who have taken the initiative to sit down with Chinese peers at these organizations and platforms, perhaps it hasn’t worked. But it’s an important step in documenting the issue and saying, this is happening. And why aren’t you listening to us? It adds weight to the evidence. So that role is important too.

Joyce Chan: The reactions of these Chinese scholars, and the possibility of speaking out for Africans in China on the back of this documentary, all highlight some of the farther-reaching consequences of your documentary.

Runako Celina: Yeah, absolutely. At least on the Africans in China front. For years when something would happen in China, people would turn to Wode Maya, the YouTuber. So when Lu Ke’s video came out, people sent it to him. First of all, because he has a platform. But secondly, because he’s safer in saying things [being outside of China]. That’s often the African approach [to these issues], to find people who are outside [China] or are willing to take the risk, people who can speak on our behalf. Because there’s a feeling we wouldn’t be able to say these things safely. It’s happened with the Guangzhou situation as well.

Joyce Chan: Summing up, what do you think the impact of your documentary has been? And do you have plans for similar stories in the future?

Runako Celina: The audience or market for this content is not exclusively Chinese. You also see markets now in Japan and elsewhere. But because so much of it is coming from China, my main goal was for the issue to get through to China. In terms of impact there, although we haven’t seen strong domestic responses from people in government, some of the big African YouTubers, or accounts that focus on Africa from a Chinese perspective, were very vocal and did put out their own statements or responses to this type of content.

There was one really vocal article with a capitalized headline saying, “STOP FILMING THESE VIDEOS IN AFRICA.” It has been promising to see that. But it still feels like pockets, and I don’t feel satisfied that there’s no market for this content any more. With the dubbed version of the film in Chinese coming out, obviously despite the limitations of BBC being blocked in China, I’m hoping that it will find at least some of its way across the firewall and maybe also have the impact of emboldening people to be more vocal about these issues and to consider them more.

Joyce Chan: Future plans?

Runako Celina: I’ll be continuing with investigative documentaries, and building my open source investigative skills and portfolio. I will also continue to build and structure a community around Black Livity China to amplify African/Afro-diasporic voices in the Africa-China, Black-China, China studies spaces.

The BBC documentary “Racism for Sale” can be viewed online HERE.

Joyce Chan