When Xi Jinping set the tone for his first leadership conference on the internet and cybersecurity policy in April 2016, he drew on the wisdom of China’s past. Quoting from the Han dynasty Records of the Grand Historian, a foundational text dating back to the 1st century BC, he said: “The intelligent hear through the silence, and the perceptive see through what is yet unformed.”

For the Chinese leadership today, the intelligent control of public opinion is about perceiving and removing political risks to the regime by seeing through mountains of data in a rapidly changing information landscape. Party leaders like Xi Jinping see this as a grand and historic project powered by new technologies.

This report is a preliminary study of Chinese patents, both pending and granted, revealing how various actors – including the defense industry, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), universities, and private corporations – have responded to Xi’s call and enabled the state to monitor and regulate the internet. While it is difficult to know just how widely specific patent-registered technologies have been used in practice, the patents nonetheless offer a glimpse into the state’s priorities and methods in policing online activity and guiding public opinion.

The intelligent control of public opinion is about perceiving and removing political risks by seeing through mountains of data in a rapidly changing information landscape.

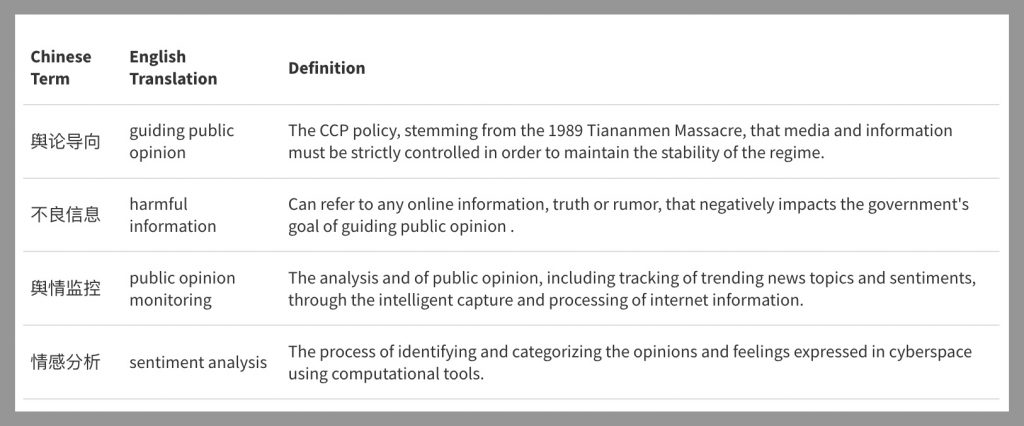

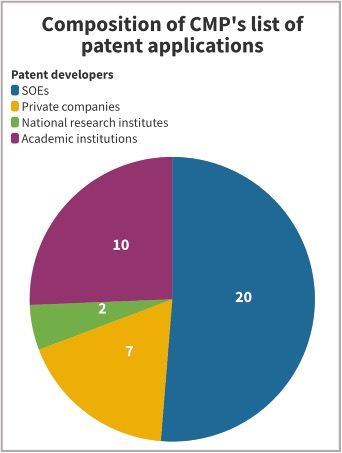

Using several keywords directly related to the government’s management of cyberspace – including “public opinion monitoring,” “harmful information,” and “sentiment analysis” – the China Media Project isolated a list of close to 40 Chinese patent applications submitted from 2012 to 2022. The majority of these patents were designed either by tech companies or SOEs, though about a quarter were generated by academic institutions.

In this article, we focus primarily on 20 patent applications submitted by the China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC), a state-owned military technology supplier that has, by the admission of one former top executive, closely studied and put into practice the vision outlined in Xi Jinping’s April 2016 speech. The group’s current top official is Chen Zhaoxiong (陈肇雄), a former deputy governor of Hunan province who served for nearly five years at the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology before taking the helm at CETC.

China’s Cybersecurity “National Team”

CETC is widely known as a state-owned umbrella enterprise specializing in dual-use electronics. Its links to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and alleged involvement in human rights abuses have also prompted US sanctions on some of its research institutes and subsidiaries, including Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology, the world’s largest manufacturer of surveillance equipment.

Besides military electronics, CETC places a strong emphasis on cybersecurity. It brands itself as the “national team in cybersecurity and informatization work” (网信工作国家队) and the “strongest central SOE” in the research and development of electronic equipment and instruments used for domestic public security purposes. CETC also lists “strengthening cybersecurity” as one of its four major goals.

CETC was formerly a scattered group of research institutes administered by the Ministry of Information Industry, the predecessor of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the agency overseeing the country’s internet and telecommunications infrastructure as well as information security.

These institutes were brought together under the CETC umbrella in 2002 under the direction of the State Council. As a central SOE, CETC is supervised by the State Council’s State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), which typically has control over top-management personnel decisions at SOEs. The group clearly states in its corporate profile, however, that it is “directly managed” by central authorities under the leadership of the CCP Central Committee, the State Council and the Central Military Commission.

Fairy Caves and Diamonds

A number of CETC’s subsidiaries specialize in the “smart” management of public opinion, public order and online activity. Among them are the CETC Smart City Research Institute and the CETC Big Data Research Institute (BDRI), both of which appear in the CMP list of patent applications. BDRI, which identifies itself as a collaborative “innovation entity” between CETC and the provincial government of Guizhou, was formed in 2017 and is engaged in big data technology research and development. It currently cooperates with the tech giant Tencent to devise solutions to public security threats stemming from technology, and in 2020, BDRI and Tencent jointly established a national engineering laboratory in Guizhou on big data applications to improve governance capacity.[1]

The collaboration included the development of the Online Societal Security Risk Situation System (网络社会安全风险态势系统), which enables early warning about possible online threats to political security, which the CCP defines primarily as risks to the regime, the socialist system, and its supporting ideology. The system, which supports the assessment of online public security risks down to the county level, prioritizes political, ideological, and economic risks, but also deals with such things as “online rumors” and vulgar popular culture.

The triangle of cooperation in this instance between a private listed company, a state-owned conglomerate and a provincial government is a testament to just how intensely the CCP has prioritized the use of big data to maintain political security – and how the premium value of data for the leadership has made related technologies a big business. During a July 2020 visit to Tencent’s big data center in Guizhou, now home to what has been called “China’s Data Valley,” Premier Li Keqiang likened the troves of data stored there to treasure. “This is a Fairy Cave,” he said. “You should dig out the gold mine. No, you should dig out the diamond mine.”

CETC Priorities: early warnings and automated functions

Our study of the patents registered and pending for CETC identifies three core priorities in the development of new technologies for the monitoring, detection, and management of information threats in cyberspace. These are (1) early warning mechanisms, which enable the proactive prediction and detection of security threats; (2) automated functions, capabilities for making decisions or generating responses to unfavorable public opinion without human involvement; and (3) visualization, the visual presentation of risk indicators in digestible forms.

Predicting and Anticipating Threats

CETC’s focus on early warning capabilities aligns squarely with the state’s goals on cyberspace administration. Being able to “hear the noiseless” and “see the shapeless,” as explained by Xi Jinping in his 2016 speech, means “knowing where risks are, what kinds of risks they are, and when they will emerge”. That involves getting an accurate grasp of the “emergence patterns, directions and trends” of cybersecurity threats.

In practice, as elaborated by Xi, this requires building a “cybersecurity risk reporting mechanism” where both the government and corporations work in unison to collect and share information and intel on cybersecurity.

The newly patented “composite city cyberspace management system” developed by CETC’s 28th Research Institute (CETC28) demonstrates how threats unformed risks are to be detected at an early stage. CETC28 houses a dedicated department for cybersecurity and was involved in “curbing online rumors” in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A subpart of the system is dedicated to “preventing and controlling” security risks posed by online content. Its early warning mechanism assesses three major indicators: the virality of an online message, how netizens react to it, and its level of “sensitivity.” Early warnings are triggered when “sensitive information” spreads and gains traction. While what constitutes “sensitive information” was never defined, CETC28 developers hinted in their patent application that “sensitive” subjects could be anything ranging from political, security or economic matters to issues relating to public health, the environment, or the livelihood of the people.

The system also aids with the focused monitoring of online “emergencies.” In “emergency response mode” the system only gives early warnings that pertain to a particular “emergency incident” (应急事件).

In the process of detecting sensitive information, “key netizens” (重点网民) and “key websites” (重点网站), which are to be subject to closer scrutiny, are also identified and tracked. But who might become “key” to public security or cyberspace administration authorities?

In the process of detecting sensitive information, “key netizens” and “key websites,” which are to be subject to closer scrutiny, are also identified and tracked.

To police organs, “key persons” include suspected terrorists, persons that are “unfavorable” to stability, which could mean a broad range of critics and dissidents, and “key petitioners,” referring to those (such as victims of forced demolition or other injustices) that have sought mediation. In the past, Chinese Internet regulators have also identified online rights activists (网络维权人士), foreign NGOs, and groups like Falun Gong as “key” targets for information surveillance. Messages from tracked “key netizens” are to be moderated in real-time by the system.

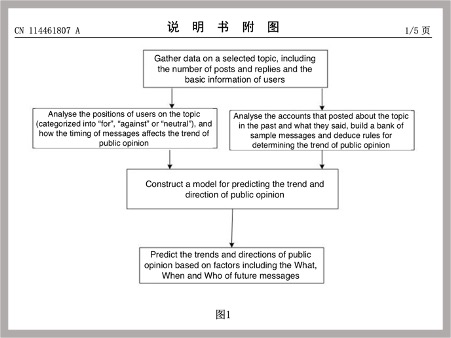

A tool developed by CETC‘s 30th Research Institute shows how trends in online public opinion are predicted. The following flowchart excerpted from the patent application demonstrates how this might be done:

The pursuit of the ability to anticipate threats also echoes the PRC’s approach to public security generally, which places a premium on “prevention and control” (防控), the ability to detect potential risks at an early stage. Xi Jinping has emphasized repeatedly to Party cadres that the key to social stability is “proactiveness in preventing and dissolving major risks” in the face of political, ideological, social and other threats. An opinion document issued by the CCP Central Committee and State Council in 2015 on strengthening the “prevention and control system for societal security” also calls for the enhancement of early warning capabilities.

Automated Responses to Threats

CETC research institutes have also made great efforts in developing technologies that “aid decision-making” (辅助决策) in regulating online public opinion. This sometimes involves the use of automated functions, including automatically identifying and predicting the behavior of “key users”, isolating repetitive social media accounts that are engaged in “spreading rumors” — which can be determining “abnormal users” that are involved in “stirring up” (炒作) activities during online “hot point incidents” (热点事件), and so on.

This is in line with the more general policy of “smart governance” for social and political control. “Smart governance” in the realm of cyberspace administration work translates into the increased use of artificial intelligence, big data and cloud computing, with the ultimate goal of transitioning from “technical administration of the cyberspace” (技术管网) to “AI administration of the cyberspace” (人工智能管网).

One patented “smart system” (智能系统) created by CETC’s 54th Research Institute (CETC54), which specializes in “counter-information” (信息对抗), takes this further. The system is developed for responding to online “public opinion emergencies” (舆情突发事件). It not only analyzes online content and detects emergencies, but also recommends a “prevention and control plan” (防控预案). The goal is to reduce the need for manually devising and coordinating countermeasures in the face of public opinion crises.

Here is how CETC54 developers explain the need for such a system:

“Online public opinion (网络舆情) is the common opinion with a certain level of influence and tendency expressed by the public on the Internet about a social phenomenon or social issue. The influence of online public opinion on the order of political life and social stability is growing by the day. If an online public opinion emergency (网络舆情突发事件) cannot be properly dealt with in time, it could very well induce the public’s negative emotions (不良情绪) and the occurrence of harmful behavior (不良行为), thereby causing serious threats to social stability. This calls for an urgent need for a technical means that could enable the automatic monitoring of online public opinion information and could provide decision-making support for handling public opinion emergencies.”

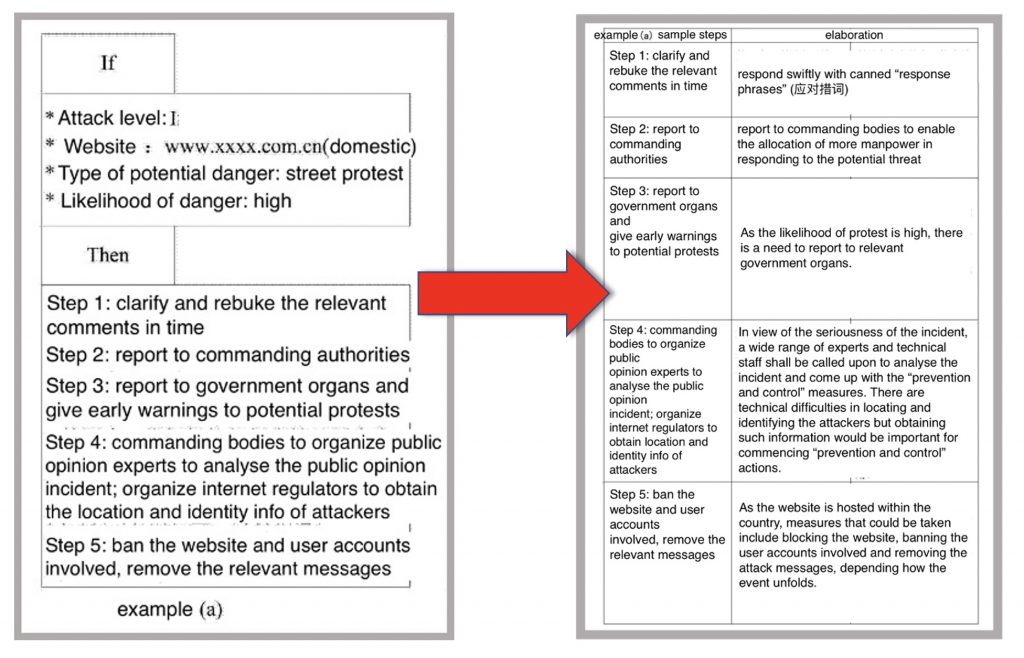

Of particular interest is how recommendations for “prevention and control plans” are made. The following hypothetical scenario illustrates how the system responds to an emergency:

Semantics and analytics of online content are first examined to detect emergencies and their origins. These emergencies are then classified in terms of their threat levels and the type of underlying danger they present. The excerpted hypothetical illustrates a scenario where public demonstrations would likely result from a “high-level” threat. The system in this case recommends a five-step “prevention and control” plan, as presented in the table above, that involves close coordination among government bodies, internet regulators, technical staff, and “public opinion management experts” (舆情处置专家) — with the aim of identifying the perpetrators and dissolving the risk of public protest in time.

The design of this system tells us that automated capabilities and artificial intelligence are meant not only to detect risks, but increasingly also to address and dissolve risks. While it is uncertain how effective the “Smart System” is in practice or how often it is now used by public security organs – in fact, developers at CETC54 made it clear that the “prevention and control plans” work only to guide proposals that require human input – it still signifies the government’s intent to routinize and accelerate responses to public opinion incidents, with a reduced reliance on manual decision-making.

Visualization of Threats

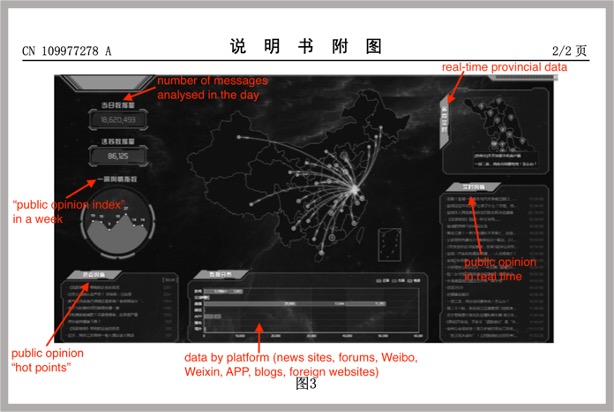

The management of online public opinion often requires close monitoring and quick decision-making. This further demands the presentation and visualization (可视化) of risk indicators. Tools developed by CETC research institutes help visualize data such as the distribution of public opinion “hot points” (热点) across geographical locations, the frequencies of monitored “keywords,” the sentimental tendencies of netizens towards a certain “hot topic,” and so on. This helps the authorities improve efficiency in making risk assessments and responding to “public opinion emergencies.”

Under Xi Jinping, the CCP has made its goals clear to Party and government leaders within the larger project of keeping China’s cyberspace politically secure. His insistence on the need to proactively look out for and dissolve potential risks is driving a wave of new technologies designed for that purpose. By making use of tools developed by defense and tech giants such as CETC, China’s security authorities and internet regulators are becoming more capable of eliminating unformed threats to cybersecurity in China.

As Xi said at the first leadership conference on the internet and cybersecurity policy in 2016: “Not realizing where risks are is the biggest risk of all.”