Image of Mao’s portrait over the entrance to the Forbidden City, by Pixinn.net available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.

For the Chinese Communist Party, history is never in the past. It is a political text to be imprinted with a vision of power and its legitimation; a culmination in the present, gathering on the selective foundation of what has come before. It follows, naturally, that history is never simply written. It is drafted in consultation, making its way from one office to the next, approved and rejected, revised and re-revised, chiseled into being like a cathedral of rhetoric and representation — until what emerges is a monument to the Party’s image of itself at that concrete moment in time.

It is in exactly this spirit that we should understand “A Chronicle of Major Events Since the Party’s 19th National Congress” (党的十九大以来大事记), the declaration of the Party and its purpose that today dominates most of the first eight pages of the CCP’s official People’s Daily newspaper. Like the communique released earlier this week, the “Chronicle of Major Events” is one of a number of official documents that we can anticipate in the run-up to the 20th National Congress of the CCP, set to open on October 16.

The last such chronicle was released in the People’s Daily on October 16, 2017, two days before the opening of the 19th National Congress.

This year’s “Chronicle of Major Events” comes with a special commentary marking the release, printed on page two, as well as a dry question-and-answer recounting on page eight, with an unnamed official from the Central Institute of Party History and Literature (中共中央党史和文献研究院), of the process and principles by which the document was formulated.

The attribution of the commentary to “a commentator from this paper,” or benbao pinglunyuan (本报评论员), marks it as an important staff-written piece representing views in the senior leadership. The commentary concludes with a packed paragraph of loyalty signaling that references the power of Xi Jinping’s guiding philosophy, or “banner term” (旗帜语) — which is expected to be shortened at the upcoming congress to the potent “Xi Jinping Thought” — as well as formulas like the “Two Establishes,” which is meant to seal the position of both Xi and his guiding ideas.

“The banner points the direction; the direction determines the path; the path determines destiny,” it reads, sending a clear message that Xi’s “thought” is the way of the future for China.

Drafting the Past for the Future

The question-and-answer article from the Central Institute of Party History and Literature is mostly uninteresting in its fawning restatement of CCP orthodoxy. The question is asked, not by a human being but presumably by the Institute itself: “Could you please talk about the guiding thought and basic principles in the preparation of ‘Major Events’?” The answer comes from the unnamed “responsible official”: “The writing of ‘Major Events’ adheres in its guidance to Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era.”

Not exactly gripping or revelatory.

The banner points the direction; the direction determines the path; the path determines destiny.

— The People’s Daily, October 14, 2022

But the Q&A’s sketch of the procedural process behind the “Chronicle of Major Events” might be interesting to observers of Chinese politics. It explains that a series of internal CCP chronicles since the 19th National Congress in 2017 laid down the foundation for the “Chronicle of Major Events” and that work on these documents “gathered experience and trained the team” at the institute. These official historical documents included “Major Events in 40 Years of Reform and Opening” (改革开放四十年大事记), released in 2018, and “Major Events in a Century of the CCP” (中国共产党一百年大事记), released in late June of 2021.

Early this year, in anticipation of the 20th National Congress, the institute defined the drafting of the “Chronicle of Major Events” as one of its top priorities, and formed a “drafting team” (编写组). The drafting process then involved numerous internal meetings to discuss various issues as they emerged. Once an initial draft had been produced, experts were organized to further discuss the draft and make suggestions. “The more than 500 entries were revised word by word, polished repeatedly, and drafted several times,” according to the Q&A.

“It can be said that ‘Major Events’ is an important research result completed under the kind care of leading comrades of the Central Committee with the full effort of Party history and documentation departments, and with collaboration from other relevant departments,” the anonymous official concludes.

The nod to “research” aside, this is not the work of professional historians. What to include, and what to leave out? Whom to downplay and whom to emphasize? Such questions are too momentous to entrust to academic historians. The process must instead rely on those we might call, for lack of a better word, historiogrofficials — bureaucratic functionaries who shape the past through the political prerogatives of the present.

So what shape has the “Chronicle of Major Events” taken?

Visualizing the Past Five Years

It would be a mostly pointless exercise to delve into the 500-odd entries in the chronicle, but the consistency of these documents, in terms of form and process, as they are released every five years provides an excellent opportunity for comparison. And one crucial indicator we can observe is how frequently the chronicles mention the Party’s top leaders, the seven men on the Standing Committee of the Politburo.

Comparison is feasible not just because the process, as the official from the Central Institute of Party History and Literature explained, is a highly formal one. The chronicles released in 2017 and 2022 are also nearly identical in length, the former coming in at 49,949 characters, and the second at 50,800 (being just 16-20 lines longer).

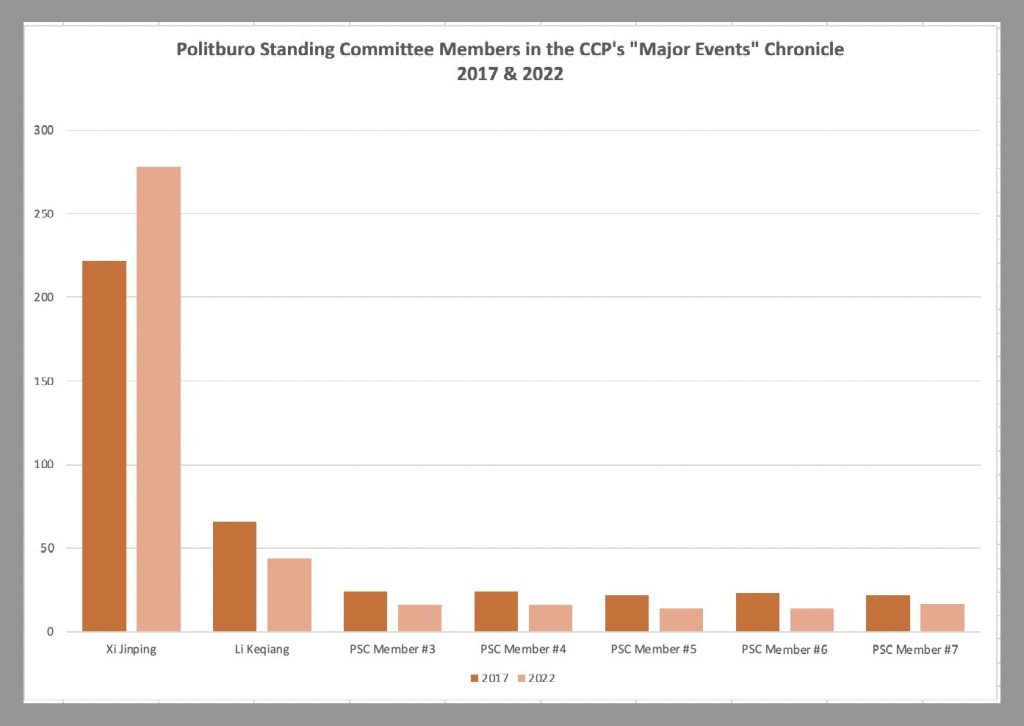

If we search full-text versions of both chronicles for the names of the seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee, and then plot the number of mentions for each name, a clear pattern emerges.

The rise in mentions of Xi Jinping in this year’s chronicle (268) represents just over a 25 percent increase over his mentions in the 2017 chronicle (222), clearly reflecting his growing profile within the official account of the past five years.

As for the remaining members of the Standing Committee, the total mentions of all have fallen in real terms, despite the very slight increase in the length of the chronicle. Premier Li Keqiang, the second-ranking official on the PSC after Xi, received 66 mentions in the 2017 chronicle. This year, Li received just 44 mentions, a significant drop of one-third.

Drops for the rest of the PSC members in this year’s chronicle are similar to that experienced by the premier. For example, the third-ranking member in 2017 was Zhang Dejiang (张德江), who had 24 mentions in the full text. In the chronicle released today, the third-ranking member, Li Zhanshu (栗战书), has just 16 mentions, a drop again of one-third.

This yawning gap between Xi and the rest of the top leadership, and the shaping of history around his person and leadership, is not exactly a surprise, of course. It recalls what we saw back in November 2021 with the release at the Sixth Plenum of the CCP’s third resolution on history, the Resolution of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party on the Major Achievements and Historical Experiences of the Party’s Hundred-Year Struggle (中共中央关于党的百年奋斗重大成就和历史经验的决议).

That decision announced a new direction for the CCP and reconsolidated its claim to legitimacy under Xi’s leadership in the “New Era” (新时代). And it was certainly no accident that Xi’s decade in power, a period covering just 10 percent of the Party’s entire 10-year history, dominated more than one-half of the resolution.

No one can yet say with a great deal of certainty what the 20th National Congress of the CCP will bring. But in the version of the past offered by today’s “Chronicle of Major Events,” we can certainly see glimpses of the very near future.