Was it a “serious mistake” or a wilful and desperate act of protest against worsening press controls? This question remains unanswered one week after a headline news editor at the Shenzhen edition of Southern Metropolis Daily, Liu Cuixia (刘翠霞), was fired for her role in a peculiar media scandal — an incident that top political brass at the paper’s publisher, the Nanfang Daily Group, characterised in an internal release as “a serious matter of guidance.”

The scandal was prompted by the unfortunate — or defiant? — pairing of two headlines on the front page of the Shenzhen edition on February 20. The bold headline across the top of the page referenced President Xi Jinping’s “important speech” made the previous day in Beijing, in which he stressed the Chinese Communist Party’s supremacy over all media: “Party and Government Media are Propaganda Positions and Must Be Surnamed Party.”

Directly below this banner coverage — which all Chinese media were under orders to prioritise, along with a photo of the president’s tour of core central Party media — was a large photo of the spreading at sea of the ashes of Yuan Geng (袁庚), a key founder of the Shekou Industrial Zone. Yuan, an important local businessman and reformer, died on January 31 at the age of 99. The headline of this article read: “A Soul Returns to the Sea.”

The juxtaposition was either so canny or so casual few might have noticed at all. But once eagle-eyed Chinese internet users had noted a certain friction between the lines, the static energy quickly became electric. If the two headlines were read together vertically, people realised, the “hidden-head” message would be as follows:

媒体

姓党

魂归

大海Media Are

Surnamed Party

Their Souls Return

To The Sea

The editors, it seemed, were suggesting that the severe controls on Chinese media Xi Jinping outlined in his February 19 speech were a death sentence for all semblance of journalistic professionalism — the last nail in the coffin.

In its statement, the Party committee of the Nanfang Daily Group suggested the editors had merely lacked “political sensitivity,” committing a serious error that had been “interpreted maliciously by others online.”

Staff at the Southern Metropolis Daily have suggested the editors would never knowingly have taken such risks. “It can’t have been deliberate,” one anonymous journalist told the New York Times. “It’s just very, very serious. And these days no one would dare to do something like that.”

Yes, these days indeed. These days are exactly the point.

Intended or not, the message about these days comes across loud and clear between the unfortunate headlines. Xi Jinping’s controls on “news and public opinion,” and in fact on all forms of expression and dissent, have become so draconian that to many the spirit of reform in China seems, like Yuan Geng’s ashes, to be slipping into the depths.

In his February 19 speech, Xi Jinping spoke of the need for “innovation” in the arena of media control, increasing the reach, influence and “infectiveness” of propaganda. During a visit to the People’s Liberation Army Daily back in December, the president described propaganda as a kraken-like monster, its arms twisting through the media-saturated lives of the public. “Wherever the readers are, wherever the viewers are, that is where propaganda reports must extend their tentacles,” he said, “and that is where we find the focal point and end point of propaganda and ideology work.”

But the kraken induces not interest or attraction, but terror. And if the kraken inspires “innovation,” it is defensive only.

For the nearest analogy to the preposterous level of panic and paranoia at work in the recent Southern Metropolis Daily headline scandal, we must return to the tail end of the Cultural Revolution, and to the very newspaper where China’s kraken-in-chief aired his comments last December on the “innovation” of control.

The “Black Box Scandal” (黑框事件)

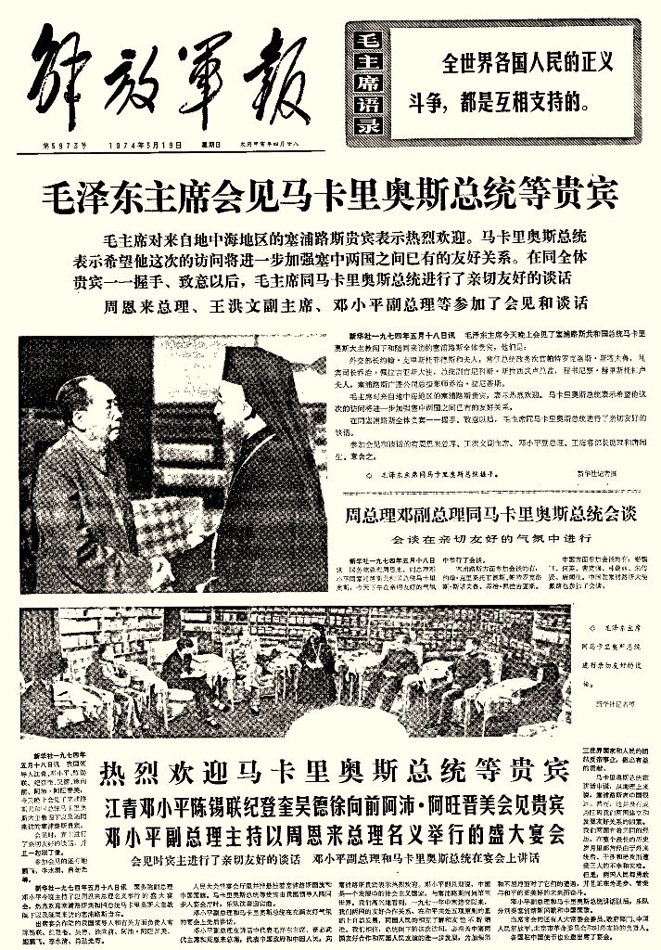

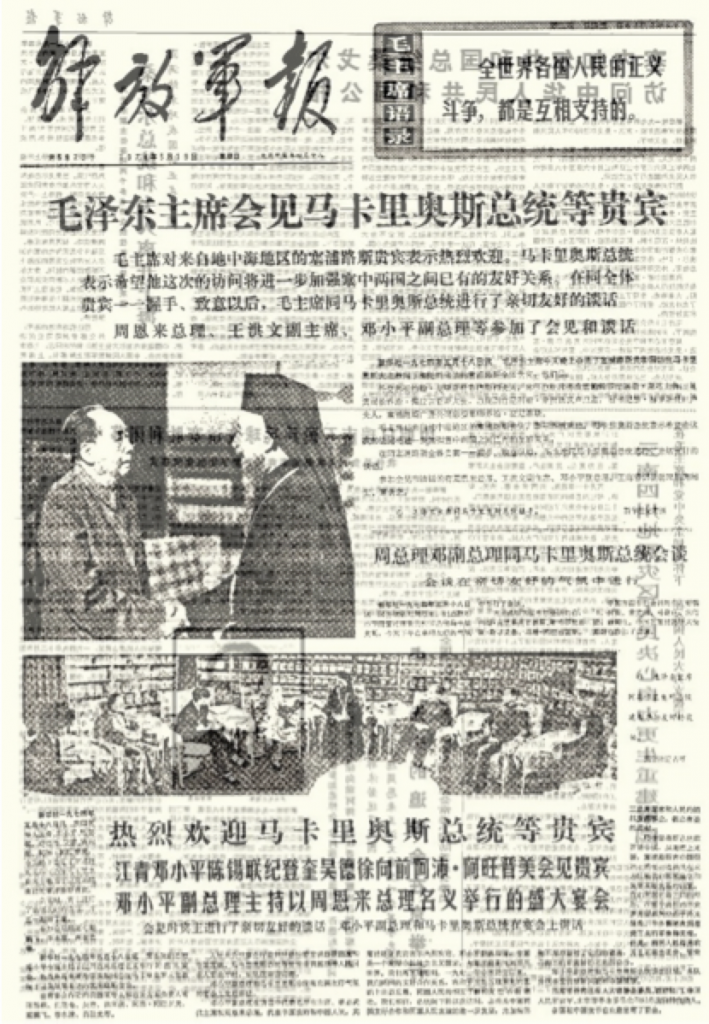

It was early evening on July 8, 1974. One by one, the members of the Party committee of the People’s Liberation Army Daily — the official mouthpiece of the military and one of just three publications dominating China in the midst of the Cultural Revolution — received phone calls summoning them to the newspaper’s conference room for an unspecified urgent matter.

The senior editors of the PLA Daily crowded into the conference room. Finally, in walked the young deputy editor from the newspaper’s “Criticize Lin Biao, Criticize Confucius Office.” From his leather satchel he withdrew several copies of the paper and said sternly: “Comrade Hu Wei (胡炜), chairman of the military commission’s Criticize Lin Biao, Criticize Confucius Office, has sent me here with instructions from the centre. Recently, leading central Party comrades received a letter from the masses pointing out that there is an overlap between the funeral picture of Mr. Lu Han on page two of the May 19 edition of the PLA Daily, and the picture on page one of Chairman Mao meeting with a foreign guest.”

“This is a serious political error,” the deputy editor continued. “The emergence of this problem is surely not an accident.” He read out a letter, dated June 25, from Mao Zedong’s fourth wife, Jiang Qing, in which she demanded a thorough investigation of this “serious political incident.”

An overlap? What could the young editor possibly have meant?

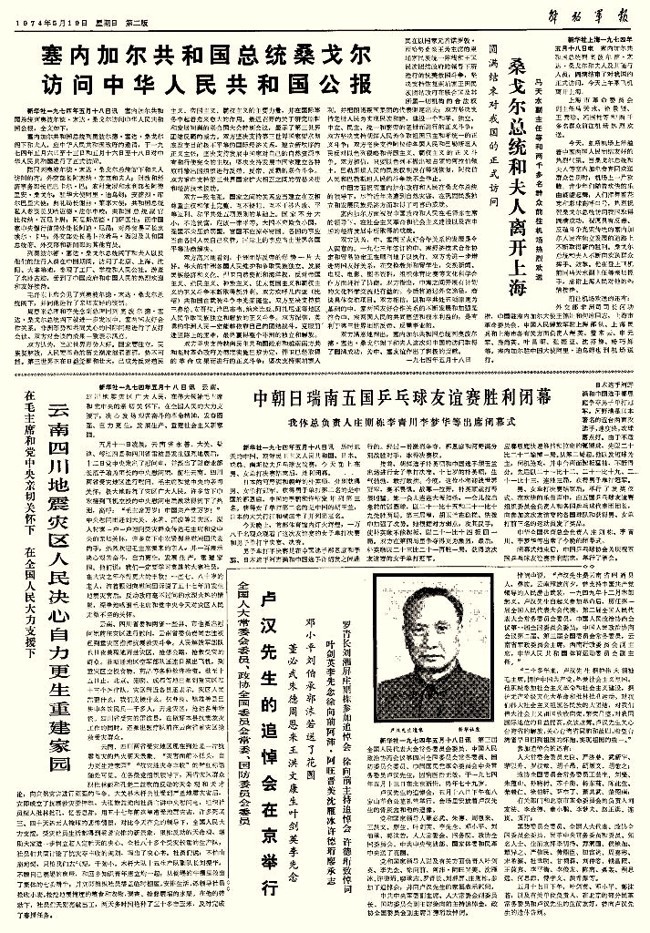

As it turned out, the PLA Daily had run, on page two of the May 19 edition, an obituary for Lu Han, the former Kuomintang general who had defected to the Chinese Communist Party in 1949. As was customary, editors had included a photo of Lu bordered by a thick black box, which in China symbolises death.

Page one of the paper had featured coverage of Mao Zedong’s meeting with Makarios III, the first President of the Republic of Cyprus. In an image below the fold, Mao Zedong was pictured sitting in a meeting room with Makarios III.

Separately, the pages were fine. But when the newspaper was held up to the light, the black border around the page-two photograph of Lu Han became a black box around the image of Mao Zedong.

The following composite image is an approximation of what the reportedly scandalised PLA Daily readers would have seen as light filtered through pages one and two on the morning of May 19, 1974.

As in the case of the recent Southern Metropolis Daily incident, there was an immediate question of intention in what became known as the “Black Box Scandal.” Had the editors knowingly designed the paper in such a way as to curse the unassailable Chairman Mao?

Likewise, just as the political implications of the recent Southern Metropolis Daily headlines had to be teased out by Chinese on social networks, so had the “Black Box Scandal” been illuminated — ostensibly, at least — by “the masses.”

The above account of the “Black Box Scandal” comes directly from Wu Yongchuan (吴永川), a former deputy director of the PLA Daily who was on duty with another editor, Xue Zhen (薛真), as the May 19, 1974, edition went to press. Wu gave a detailed account of the event in the December 21, 2000, edition of Guangzhou’s Southern Weekly.

According to Wu, a full investigation was conducted into the incident and both he and Xue Zhen were compelled to make full and public self-examinations. The PLA Daily was ordered to make all necessary adjustments to ensure that such offences were not repeated.

And so it was, Wu writes, the PLA Daily became the first newspaper in China to set up a special “searchlight table” (探照桌), its top made of transparent glass under which could be placed an electric bulb. As the proofs were reviewed each night, editors studied pages one and two, pages three and four, and so on, ensuring there were no political violations — real or imagined. The process was called “searchlighting” (探照).

In his essay, “The Reputation of Millions Can’t Stand Up to One’s Man’s Ruin” (万人之誉不及一人之毁), Zhang Xinyang (张心阳), one of Wu Yongchuan’s former colleagues, tells us that “searchlighting” was eventually extended to the inspection of the Chinese characters appearing on the backs of photographs of Communist Party leaders. The editor responsible for searchlighting had to ensure that no words with negative connotations — like “death,” “overthrow” or “criticise” — appeared on the backs of such images. If possible infractions were found, the pages had to be scrapped and redesigned, even if that meant the edition came out late.

“Searchlighting” at the PLA Daily continued through the end of the Cultural Revolution. For Zhang Xinyang, the process was a grotesque anomaly — “a great invention,” he writes acerbically — highlighting the political excesses of that painful time.

Zhang writes: “It entirely surpassed conventional human thought, and innovated methods of reading the newspapers in ways not seen before or since, an entry in the annals of press history.”

But history, when not properly regarded, has a way of returning, kraken-like, from the depths. Xi Jinping’s fearsome “innovations,” should they continue, are likely to spawn new and yet oddly familiar absurdities — “searchlighting” for the 21st century.

The former PLA Daily deputy director, Wu Yongchuan, closed his December 2000 account of the “Black Box Scandal” by conceding that the political context of his experience must seem remote to his contemporary readers.

“I’m afraid,” wrote Wu, “that readers today would find it difficult to imagine such trials and tribulations in getting a newspaper out, or such a way of reading a newspaper.”

Ah, Wu Yongquan!

But these days. These days . . .

[This essay was originally published by CMP in March 2016.]