Finding a Path to Critical Thinking in China

Fang Kecheng

Lan Fang and Guo Zhaofan

Fang Kecheng: Hello to both of you. Would you please first introduce yourselves? Especially sharing your experience before starting Plan C.

Lan Fang: I’m a journalist. I studied law at the China University of Political Science and Law for my undergraduate degree. Afterward, I did a postgraduate degree at the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po) in Human Rights and Humanitarian Action. After graduation, I worked as a public policy reporter for Caixin magazine and Caixin Media.

Guo Zhaofan: I studied accounting at Tsinghua University for my bachelor’s. After graduation, I worked in finance and auditing for several years. Later, I became more interested in public welfare and changed my career to charity work. At that time, I met Lan Fang at the 21st Century Institute of Education, a charity organization.

Fang Kecheng: You have another co-founder, Ye Mingxin. What kind of background does she have?

Lan Fang: Mingxin also studied law. She did her undergraduate degree at Peking University Law School and her master’s degree at Columbia Law School. Since graduation, she has been working as a front-line legal aid lawyer. Mingxin has also done a lot of legislative advocacy work related to labor laws, occupational diseases, and work injury prevention. We knew each other in school, and because I was a public policy reporter, we followed some of the same cases and worked together. I’ve joked before if you search our names together, you’ll see a lot of cases that she worked on as a lawyer — ones I also covered as a reporter. Afterward, we worked on Plan C together.

Fang Kecheng: The three of you have backgrounds in law, media, education policy, and even finance. What brought you together?

Lan Fang: Mingxin was pulled in by me, so I’ll start with my story. Because I have always been a public policy journalist focusing on civil society, I became concerned about the development and changes in China’s public opinion field. So while working as a journalist, I got the idea to do a project on civic education. I took advantage of being a reporter, which gave me the opportunity to study projects related to civic education at home and abroad. Eventually, I found an entry point [for the project] — critical thinking, and public reason.

Guo Zhaofan: Looking back, a few experiences significantly impacted me. One was during a summer vacation in college when I took a school field trip to Jiangxi’s countryside. We learned that many rural residents had lost their land during the process of urbanization. Their living conditions hit me particularly hard. I realized my understanding of China’s rural society was especially limited. Although later I found my way into a career in finance, I never forgot this experience. So, later on, when I changed to doing charity work, including the creation of Plan C, one thing I was really clear about was that I wanted to pay attention to and solve social problems, care for disadvantaged groups, and take on social responsibility.

The second experience was when I returned to China after graduate school. I wanted to do education, so I joined the 21st Century Institute. At the time, we wanted to look at various individuals and institutions in China doing innovative education work. During this process, I talked to many educators and came across the concept of critical thinking. After doing a lot of research, I realized that much education in the West ultimately is about the cultivation of critical thinking. All disciplines are very closely related to it. However, even though the people I rub shoulders with in China are the most pioneering reform types, very few of them ever raise the issue of critical thinking — particularly at the level of pre-university education. Only a handful of people can take what exists in the West and teach it more systematically. So I felt that this was something I wanted to do.

Fang Kecheng: Can you talk a bit about what exactly critical thinking is? It’s a term that people often bring up, but it’s not something that is always clearly explained. For example, does critical thinking mean emphasizing criticism? Does it mean criticizing everything? What is the relationship between critical thinking and other words we often use, such as independent thinking?

Guo Zhaofan: One of the keywords that critical thinking emphasizes is questioning. But it’s not just questioning others. It’s actually more challenging to question ourselves, including reflecting on some of the ideas we hold in our minds. The second keyword is pluralism, meaning we should listen to any issue from different perspectives. Consider opinions that are different from our own and the rationale behind them. The third keyword is rationality, which means to draw conclusions based on reasoning, to be factual with a focus on evidence.

Critical thinking is a reflective way of thinking that helps us determine, based on all the information we receive daily: What am I going to believe? Which ideas are reliable? Which information is false? We have to make all kinds of decisions and communicate with many people daily; in this process, we have to express our views. How can I be sure that the opinions I express are substantiated? Do you provide enough evidence to convince others, and is the argument process convincing with reason? These are the questions that critical thinking responds to.

Critical thinking is a reflective way of thinking that helps us determine, based on all the information we receive daily: What am I going to believe? Which ideas are reliable? Which information is false?

Lan Fang: The two concepts of critical thinking and independent thinking are very close to each other. Critical thinking ultimately leads to independent thinking, independent ideas and an independent personality —because you have to decide through your own thinking and judgment what you should believe and what you should do.

Fang Kecheng: I think there is a presupposition: you don’t need to be particularly intelligent or have a lot of information at hand, or even have an exceptionally high level of education. Ordinary people can make independent and reliable judgments after some training. Is that the case?

Lan Fang: Civic education (公民教育) and critical thinking education (思辨教育) have three aspects: knowledge, competence, and character. Suppose you want to be an independent thinker and learn to think critically. In that case, you should be a questioning person, tolerant, diverse, open-minded, and believe in evidence, facts, and reason, which is the foundation of character.

On the other hand, there are the competencies and skills I just mentioned. These are what we share and discuss the most in our classes. How do you go about making a rational analysis and judgment? There really are certain tools and methods you can apply. As you said, mastering them doesn’t necessarily require you to be a very educated person. What remains, then, is the necessary knowledge. Having an independent opinion on a specific topic still requires a certain level of background knowledge. Of course, you can search to gain a better understanding.

Why women are more willing to learn to think critically

Fang Kecheng: I’m curious, after training so many children and adults, do you think that “character” — qualities such as the open-mindedness you just emphasized — is something that can be cultivated and changed? Or is it an innate personality trait?

Guo Zhaofan: It’s best to start at a young age. It’s harder for adults to break out of their mindset. Also, there is a process involved in hearing something, and then applying it, and then making it a habitual part of how you think. Many adults may understand the lessons, but applying them in their daily lives is the hard part.

Lan Fang: There are definitely both innate and nurtured factors. Character is related to certain personality traits that we are born with, and it is definitely related to our upbringing and to the educational experiences we have.

When we first started Plan C, we started with adult critical thinking education and didn’t start sessions for children until 2019. One fascinating observation we had is that about 70 to 80 percent of adults who pay for training in critical thinking are women. They all mostly live in first-tier cities and are well-educated women. One of the nagging issues they communicate is how to change the perspective of their fathers and partners. There are definitely certain people who have more of an innate sense of equality, open-mindedness, and reflection than others.

Fang Kecheng: Why is that?

Lan Fang: Power structures may be at play. It may be more difficult for the privileged to accept alternative views in a family, a school, an institution, or a society, and it’s more difficult to take challenges from the weaker side. It may be more difficult to change one’s entrenched views.

Guo Zhaofan: We talked to a major platform about cooperation. They wanted to launch a course. We had several rounds of talks and submitted some versions. Later, the platform gave us feedback that 70 to 80 percent of its users were men, most over 30 years old, and relatively successful in their careers. Their perception was that this group would be more concerned about how to achieve success than how to self-reflect. Our whole starting point is that all of us must question ourselves, reflect and rethink many of the things we believe in, and reconstruct our systems of thought. The platform felt that the tone was really unsuited to them.

Fang Kecheng: That makes sense. Initially, you did a lot of training for rural teachers, right? So that they could pass the ideas on to their students in the villages. Is this work still happening?

Lan Fang: We hit the pause button on the adult and teacher programs. The courses are still there, but we haven’t done any further development. We are concentrating on children.

We previously did the 21-day rural teacher training course. To be honest, we knew the course was relatively superficial. It wasn’t that the content of the course was simple. Rather, what you find is that when you present the concepts to teachers, they understand them just fine. It’s just that when it comes to translating them into actual daily teaching across subjects, there is a huge gap.

Another issue is the varying quality of primary school teachers in China. This would require us to do a lot of very detailed and specific course designs. A language teacher, for example, might expect us to give them a very clear textbook with a teaching guide for each lesson — clearly stating new ways they can teach a language text and how they can specifically lead the children to discuss it.

We weren’t able before to provide such detailed content for subject teachers. But now we have the confidence. For four years now, we’ve been doing our own guided reading program, and maybe in two years we’ll have a complete curriculum for grades one through nine. We have also accumulated a lot of experience in front-line teaching. We can produce detailed curricula, teaching methods, and notes packaged into a curriculum that is available open source to teachers in rural areas, enabling more children to have access to such courses. Of course, this is only a very preliminary idea. If we want to implement it, there will be a lot of issues, such as intellectual property issues and operational questions. But in any case, this is our longer-term vision.

Fang Kecheng: Is it a market choice to switch from training adults to focusing on children, or is it because you think it’s too difficult to change the mindset of adults, so you might as well put the whole effort into children?

Lan Fang: Both are true. On the one hand, there is definitely a market demand. When we first started Plan C in 2016, we didn’t realize that we were entering the so-called “paying for knowledge” (知识付费) trend, but this trend passed very quickly. Only some of the largest platforms and IPs are left in the market. With a small organization like ours and in the relatively neglected field of critical thinking, we must adapt our strategy to survive in the marketplace. So, at that time, we had to change our target customers.

On the other hand, this is also something natural when it comes to education — that you should start with children. We cooperated with many educational institutions from early on. We did a lot of training for teachers, and the teachers would say: You’ve taught us so much here, why don’t you just go and teach the children directly, wouldn’t the effect be better?

We started doing in-person programs for kids in 2018. And from 2019, we started to do the online version of the children’s critical reading program we’re doing now more systematically.

Fang Kecheng: Parents are willing to pay for their children’s education. What is the approximate family background of the children you are reaching now? Are they all from the middle class in big cities?

Guo Zhaofan: Middle-class families in first and second-tier cities are still our main focus. The course fees will give you an idea. A full year of kids’ courses is about five to six thousand RMB. They pay four installments over the year, so each installment is between several hundred and a thousand yuan. This price point is not that high compared to many other programs on the market. So many of our parents are still average middle-class families. We could have set the price point higher and made the class size smaller or just served international schools or wealthier parents, but that’s obviously not in line with our goals. So we’re not considering that direction.

We have a small group of parents who are working class, but it’s just a few. For our long-term vision, we still want our curriculum to reach rural areas and more left-behind (留守儿童) and migrant children. This is what we’ll probably do next.

Recognizing the complexity of the world through reading

Fang Kecheng: After developing so many programs and teaching so many children, what insights can you share with us?

Lan Fang: I should start with why we use reading for critical thinking education. What is critical thinking teaching? Critical thinking’s core teaching is argumentation. So how do you teach people how to present an argument? There are many different schools of thought in this country and abroad. Some believe critical thinking should be taught as a separate course, specifically on the methodology of critical thinking. Another school of thought is that these methods should be integrated into everyday course-based education, perhaps with language subjects, but also with science and technology.

Some schools are interdisciplinary and use PBL — whether that means problem-based learning or project-based learning. Because when you get a project, from the beginning of information gathering to the final output of a solution, the whole process applies critical thinking skills.

When we first started developing the curriculum for children, we chose the methodological path, specifically to teach children about critical thinking. For example, how to learn to think like a journalist, which is about information literacy; how to think like an entrepreneur, which is talking about decision making; and how to think like a lawyer, which focuses on presenting arguments. It’s about teaching students how to recognize fallacies. But then we found that if we only frame ourselves around this concept of critical thinking, the market is pretty small. Parents who would enroll their kids in such classes are limited — all highly educated or from international schools.

Fang Kecheng: The parents who already know what critical thinking is all about.

Lan Fang: Parents who are also aware of the importance of critical thinking. The average parent has no idea what critical thinking is or why it should be learned. So we decided to combine it with reading because we don’t need to tell parents how important this reading thing is. Parents see a reading class and don’t notice the critical thinking part.

The current reform of the college entrance examination system, and language teachers who constantly emphasize that “those who acquire Chinese Language and Literature gain the world” (得语文者得天下) have both helped make parents aware of the importance of reading. So parents may not be very interested in innovative or civic education. Still, they come to our program to improve their children’s reading skills and develop their interest in reading. They want their children to read more books to score higher on their exams for Chinese Language and Literature, so they come to our program.

The average parent has no idea what critical thinking is or why it should be learned. So we decided to combine it with reading because we don’t need to tell parents how important this reading thing is.

Guo Zhaofan: Actually, there are a lot of classic books for children that are worth reading. Children have limited life experience, so they need a lot of reading to enrich their lives. We may discuss seemingly abstract concepts like equality and justice, but when these are connected with the process of reading, and in the context of the main characters of the book, then the discussion is well grounded.

Many children also have a very superficial way of reading, and it’s enough for them to just know the basic storyline. And traditionally, many teachers teach from the standpoint of literary aesthetics or character interpretation. For example, this main character may be brave or selfish. The critical thinking involved in this process is weak, and there is a weak sense of openness too. We hope to guide children to more in-depth reading, so that they think more deeply about core issues in the books, in this way developing their thinking skills.

Lan Fang: The importance of reading really cannot be overstated. Reading is not only about expanding our knowledge. It also allows us to connect with the natural, wider world.

Why do we see the current state of the public opinion sphere looking like it does now? Why do netizens speak the way they do? For young children, whose life experiences are even more limited, reading is an important path to expand their life experiences, connect them with more people, and enable them to realize the world’s complexity.

Fang Kecheng: What does the process of reading look like for Plan C?

Lan Fang: We divide the reading into different levels. Superficial reading means that you read the book and what its basic story is, the causes, the process, and the outcome. You are able to read and process it. At a deeper level, there is character analysis, theme analysis, and the analysis of the author’s core ideas. So what does critical reading mean for Plan C? It is necessary to read and understand the characters and the main idea the author is trying to convey, and then evaluate the characters. If you were in their shoes, what decision would you make in this situation? Do you support this decision they made? Do you agree with the author’s point of view? Faced with the same problem, what would your point of view be?

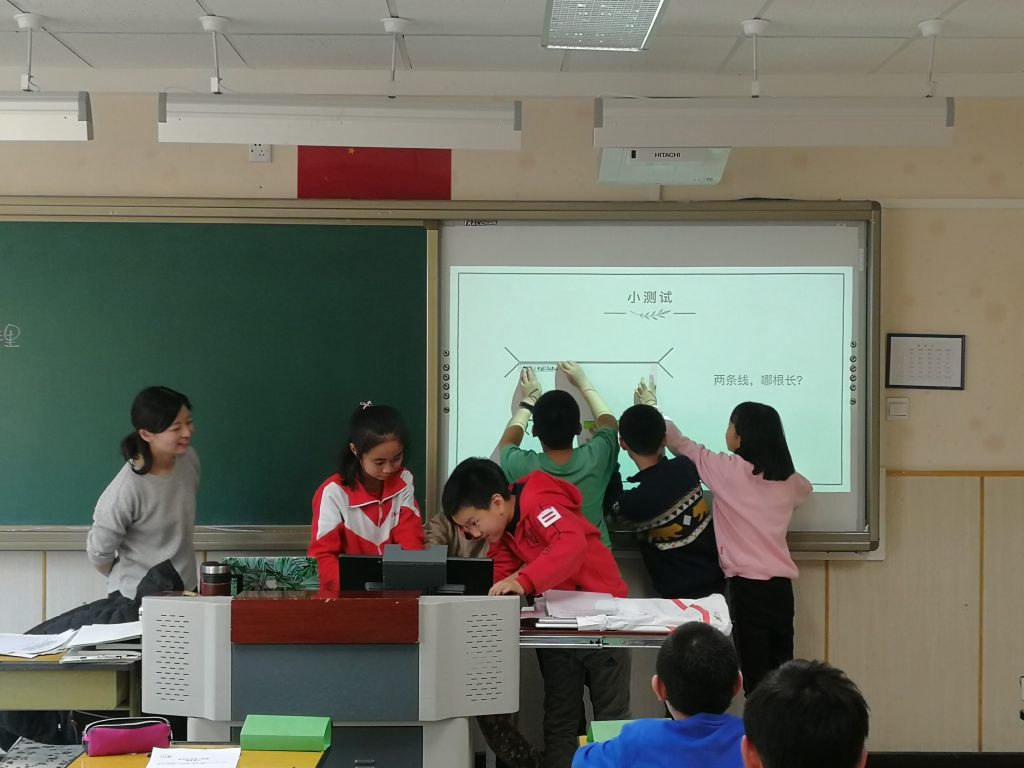

We do a lot of this in the classroom by throwing questions to the kids. It’s not just about tossing out questions, of course, but also systematically explaining the methodology. For example, when you are faced with a question of whether or not a certain thing should be done, what are the different ways you can approach the question? From the first grade onward, children in Plan C classrooms learn to see the positive and negative sides of things.

At a slightly higher grade level, they learn to identify the benefits and disadvantages of certain decisions, analyzing the good and bad aspects in a more comprehensive and structured way. In the older grades, we give them a lot of thought experiments to reflect on what values are behind different considerations. What weight do they give to these values? Why do other people assign different weights to them? What are the values that have influenced us? The final goal is to get kids out of black-or-white box thinking and to look with a constructive eye for a solution that better solves the problem we are dealing with.

Fang Kecheng: What sort of books are kids in the Plan C program reading?

Lan Fang: What kind of topics we can discuss with the kids and how deep the discussion can go is closely related to the books we select. We choose books according to the differing psychologies of children of different ages and consider dimensions like people and the self, people and the other, people and society, and people and nature.

Public issues are increasingly discussed as the grade levels advance. In terms of foreign literature, we also consciously give children works from comparatively marginalized regions to show them how people live who are from regions they don’t understand. For example, they might read I Am Malala [by Malala Yousafzai] about Pakistan; Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood [by Marjane Satrapi, about her life growing up in Iran and Austria]; On the Edge of the Primeval Forest [by Albert Schweitzer]; and The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind [a memoir of life in Malawi by William Kamkwamba and Bryan Meale]. This enables them to realize that people in other parts of the world have different ways of living and face other adversities. It will also increase their understanding of the complexity of the world as a whole.

Guo Zhaofan: Lan Fang’s examples deal with public issues, but we also have books about children’s personal lives and relationships. For instance, from the first grade onwards, we lead the children in reading picture books on emotion management and have assignments to recognize their emotions. The homework will guide them toward realizing their feelings, and also lets kids hold a family meeting to form a mutual family agreement. For example, when someone is angry at home, everyone agrees on what to do and what not to do. When someone is angry, what is the plan. And as much as possible, what not to do.

We also help kids get to know themselves. For example, how should one respond if one’s values conflict with those of classmates or if there is a conflict between parents and children? We will also discuss whether or not we should go to the teacher at school and how to perceive and respond to the problems when class leaders exercise their authority. In their daily lives, many topics involve justice, equality, and freedom.

Fang Kecheng: It sounds really great. I wonder, after these classes, do you think the kids will have learned these critical thinking methods?

Lan Fang: There are moments when it feels like we are doing something meaningful, especially in these times. We did a dystopian topic for L6 kids over winter break.

Fang Kecheng: How old is an L6 child?

Lan Fang: From sixth to ninth grade, they’re already adolescence and have their own observations and perceptions of society. For the dystopian topic, we read three books: Animal Farm, The Giver, and The Hunger Games. I found many moments in class when we talked about Animal Farm really interesting. We talked about Napoleon, the pig, how he ruled the farm, and how the animals could not resist. We also had a lesson on how propaganda ministers go about compelling and inciting the public. Children then naturally make associations with the phenomena they see in real life and reflect on and critique them.

In addition, we repeatedly stress in our class the issue of ascribing blame. When we rush to judgement about certain people or behaviors, we assume they must be doing it because they are morally corrupt or inherently evil. But we ignore many aspects and structural problems happening in the background. When we spread prejudice and say, “a certain type of person is just like that,” there is also an ascription problem behind it, so we have a lot of practice in the classroom teaching children how to make more comprehensive assessments.

Fang Kecheng: These discussions are really relatable to the students.

Lan Fang: Yes, we also talk a great deal about sexist and racially biased rhetoric in the classroom, and we use some real-life incidents of online violence for the kids to analyze. One of the questions in the assignment is: If you saw someone posting discriminatory or hateful comments on the internet, how would you respond to them? As the kids did more exercises, we realized they were capable of being the competent citizens we expected. They were capable of being rational, restrained, and reasoning with each other. In the private course group chat, they often also discussed mainstream news and posted some statements from netizens, discussing reasoning that netizens had ignored — and suggesting they would benefit from critical thinking classes. When I see messages like that, I feel really empowered.

This spring, we read Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry [by Mildred D. Taylor], a book about racial conflict in America. It is set against the backdrop of the racial persecution of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1930s. The children wrote in the comment section that a teacher said that America is a racist country that discriminates against black people and Chinese people and is terrible. We have American children in our class, so they had a very heated argument in the comments section. In fact, this is how it is in our classroom. There are moments when the children show some inherent prejudices, but through each assignment, we can still see that these children are constantly observing, constantly reflecting, and continuously growing.

Guo Zhaofan: In addition to ethnic issues, I’ve had a couple of classes on gender and have these experiences as well. It is often the boys and girls who are somewhat gender neutral and have suffered discrimination at school; they will be more active [in discussions]. Other children, on the other hand, will still be a little resistant. So it’s not easy to break down all at once. Once or twice a year, we might have a class discussing gender issues and slowly try to change some of the kids’ minds.

Finding strength in an atmosphere of political depression

Fang Kecheng: Next, let’s talk about your public-facing side of what you do. Whenever hot topics come up, you often write articles to help people sort out and analyze them using a critical thinking approach. You do this because civic education was your original intention, right?

Guo Zhaofan: Yes. All three of us have backgrounds that are more concerned with social and public issues. When we started Plan C six years ago, some flash point events happened. We would write articles using the Critical Thinking Paradigm (CTP), and we were able to gradually build up a reputation. When things happened that people couldn’t think clearly about, or just argued about, we would get messages on our WeChat account saying, “Could you write an article? Could you help us figure out what’s going on here?”

After 2019, the three of us were busy with the children’s education program, so we did less work on the public-facing content. However, this year we have written articles about the Fengxian incident (丰县事件), the Russia-Ukraine War (俄乌之战), and the controversy over China’s “Zero Covid“ policy (疫情“清零”争议). Most were pretty long, ranging from 10,000 to 20,000 words. In the future, we will follow up on particularly significant issues. Our faint voice is still very valuable in the current environment, so we want to persist [with these articles]. However, when we write future articles, we may add another approach: how to talk to children about current events.

Lan Fang: In terms of public advocacy, in addition to articles, we also do a lot of online and offline lectures. For the past few years, I would write an end-of-the-year “Circle of Friends Report” (朋友圈撕裂报告), making observations and summarizing public opinion in China over the year. So why did I stop writing it? I felt like I couldn’t take stock anymore. In the beginning, I was able to select the “Top Ten Stories” (十大撕裂事件) each year and list the most controversial events. As the years go on, you find that rifts are happening more often, cyberbullying is happening more frequently, and things big and small are happening every day. People are always able to find a flashpoint and create controversy and division.

Of course, there are still some ideological differences behind the rifts, but they aren’t so bitter as to merit the filth we often see. So it became increasingly pointless to tackle these incidents, I felt. Since there were such extreme disagreements every day, I felt I might as well spend more energy of my energy on things that seemed more microscopic. We could write an article that impacts tens of thousands of people, and the class has just a few dozen children — but I can at least see tangible changes in those few dozen children. We have substantive and constructive conversations with them. This brings more energy and strength to my life.

Guo Zhaofan: Another factor is the self-censorship that has to be done. There are lots of things that you just can talk too much about. Some of the issues you want to write about aren’t possible.

Also, more and more people this year told me our articles are too long. Over 5,000 Chinese characters or longer isn’t easy to read. This feedback isn’t the same as we received back when we started in 2016 and 2017. Many will ask whether we want to do Douyin (TikTok). I’m now doing three-minute videos, and someone said recently, “Can you do a one-minute video?” It’s really frustrating. Because for some topics we analyze one minute simply isn’t enough to really meet our critical thinking standards. There no way even to begin.

Fang Kecheng: The new social media formats are unsuitable for disseminating your articles. To put it bluntly–your articles are meant to calm people down, to get them to react without emotion. But the essence of social media is to get you to respond emotionally so that you like and share. So, your logic is the opposite of social media culture. Lan Fang just said that she felt bad writing the “Circle of Friends Report.” Would you call this “political depression” (政治抑郁)?

Lan Fang: Definitely, yes. I don’t think there’s any way to avoid it. If you’re a person of conscience, in this society, and particularly in the half year that the first half of 2022 has been, it’s hard not to be influenced by such feelings. From my own point of view, the most important part of political depression is the sense of powerlessness. No matter what you do, you will find that you may not be able to counteract or change something that has happened, the views of most people, or the so-called “base.” So, in the end, it comes back to what I can do, and as I mentioned earlier, at least in our classrooms, substantial changes can be seen.

I think that even though our current class is only for a few dozen people, it can be scaled up and replicated. It‘s possible to find a sustainable business path in China’s current environment, and it’s possible to repeat it. Whenever I think of this, I know I’m doing something meaningful.

Guo Zhaofan: This year, I’ve become more emotionally volatile. I’ve taken several actions in response. The first is to limit my time on social media. The second is to bring parents and colleagues together to read and do more in-depth things — to combat fragmentation. The third thing is to promote more actions to do more within the small scope of our company. For example, I’m in Shenzhen, where many street and community policies are particularly unreasonable, and abuse of power exists. We will lodge certain complaints, ask for the disclosure of policy documents, and so on, doing whatever we can.

Lan Fang: I’d like to add one more thing. As I mentioned earlier, I have become more disheartened over the years and have become less and less involved in the discussion of public events. But I have also persistently documented them all myself. I am very disappointed with the current court of public opinion and feel that I cannot say many things to help. But I still have a project of my own, which is to write down all these things that happen around us, including so many absurd things in the past six months, and one day, people will know their value. Our future generations, too, have the right to see another perspective and a different record. This is a private writing project of mine.

Fang Kecheng: Looking back, is there anything you have not achieved? And is there anything that has happily surpassed expectations?

Guo Zhaofan: One thing we haven’t done yet is to popularize critical thinking. We certainly hope to reach more people and want more people to understand critical thinking more deeply. I didn’t expect we would build a very structured graded reading product for children.

Lan Fang: I think after six years, we are still alive, and in fact living quite well. We’ve balanced income and costs, and been able to develop sustainably. The team is getting bigger and bigger. We experienced many policy changes and changes in the public opinion environment halfway through, but we developed steadily. I feel a pretty good sense of accomplishment. To be able to stick to the original vision for the last six years was not an easy thing to do.

Fang Kecheng: I strongly agree. I hope you can continue to steadily pass critical thinking on to more people. I believe it will also influence our public discussion in a quiet way.

Translation by Sara Yurich.

________

Featured Image: From left to right: Guo Zhaofan (郭兆凡), Lan Fang (蓝方) and Ye Mingqin (叶明欣), the co-founders of Plan C. Image courtesy of Plan C.

Fang Kecheng