The State of Surveillance in China

Joyce Chan

Liza Lin and Josh Chin

Joyce Chan: Can you start off by introducing your backgrounds? How did the idea of this book come about? And what goals did you have in mind when you got started?

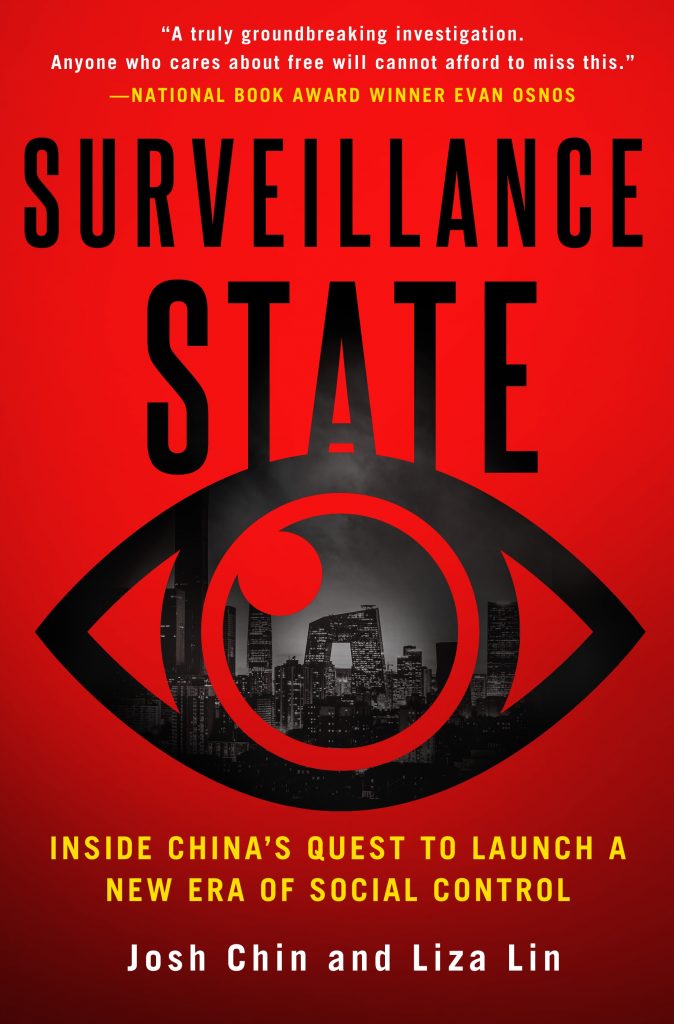

Josh Chin: We’re both reporters for The Wall Street Journal with a long-term focus on China. The book began in 2017 with an investigative series that we led for The Wall Street Journal looking into the Communist Party’s embrace of digital surveillance, which itself began when we noticed a lot of investment flowing into Chinese artificial intelligence startups that were doing a brisk business selling facial-recognition systems to police.

Over the course of our reporting, it became clear that this was more than a gee-whiz tech story. The party was exploiting data and AI in pursuit of a new, more nimble form of authoritarianism that looked like it had tectonic potential in terms of the global political landscape. It was science fiction in real life. We wanted to explore the story of that ambition in the most comprehensive way possible, with a particular emphasis on the human experience of living inside such a radical experiment.

Joyce Chan: Your book begins and ends with the account of a Uyghur poet named Tahir Hamut. Could you describe the process of choosing Tahir as the main character of the book?

Josh Chin: We got to know Tahir while reporting on the spread of surveillance in Xinjiang for a series at the end of 2017. He had recently escaped to the U.S. – essentially, he was the last prominent Uyghur intellectual to get out of Xinjiang before the doors slammed shut. At first, he didn’t want us to use his name because he was afraid of the consequences for his family. Later, he changed his mind and agreed to speak with us on the record. It was an act of real courage that gave the story – and then the book – crucial credibility and gravity.

Joyce Chan: How did you go about fact-checking the details that Tahir gave of various surveillance processes, given that so few sources from Xinjiang are willing to speak with foreign journalists?

Liza Lin: We took multiple trips to Xinjiang ourselves, including after we first interviewed him, so certain details – like what his neighborhood looked like – we were able to corroborate directly. But for a lot of details, we had only Tahir and his family to rely on. Our solution was to interview them repeatedly and only use the details that they consistently agreed on.

We also talked to several people who knew Tahir, all of whom remarked on his personal integrity and his tendency to play down his own story, which we can also attest to. Getting him to talk about his personal fears was like pulling teeth. That was frustrating a lot of the time, but it gave us confidence in everything he did finally decide to tell us.

Joyce Chan: Your book points out that China’s surveillance systems in regions with ethnic minorities like Xinjiang and Tibet can take very different forms compared to majority Han regions, such as the city of Hangzhou for example. But do you think the pandemic and China’s digital response have taken surveillance beyond regions like Xinjiang and Tibet?

Liza Lin: We had a Chinese human-rights activist tell us in 2017 that what was happening in Xinjiang was just a prelude, that the same systems were bound to be rolled out in the rest of China. We weren’t sure at the time. The levels of surveillance in Xinjiang were so extreme, it was hard to imagine them being implemented on a broad scale. But the pandemic proved us wrong. Not long after the “novel coronavirus” escaped Wuhan, you started seeing residential compounds in Beijing being locked down with only one way in or out – a system that borrowed directly from Xinjiang.

Later, you had the health code system, which tracked the movements of everyone in China and assigned them ratings according to their exposure risk. Again, there was a parallel with Xinjiang, where surveillance systems tracked, or at least purported to track, the exposure of Uyghurs to the “ideological virus” of radical Islam.

The levels of surveillance in Xinjiang were so extreme, it was hard to imagine them being implemented on a broad scale. But the pandemic proved us wrong.

Joyce Chan: How does the Chinese government use popular social media tools like WeChat in its digital surveillance of the population?

Josh Chin: WeChat is so ubiquitous within China that it’s proven to be a very effective tool in both social and discourse control. There are a few ways the Chinese government has put WeChat to use. Firstly, WeChat has become a goldmine for Chinese police in investigations or if they are trying to track down protestors and their relevant contacts.

WeChat is a super app that isn’t just chat messaging anymore. It offers users the ability to buy train and plane tickets. Many use it for mobile payments as well. Access to WeChat data has allowed national security agencies in China to retrace someone’s steps, tap his or her contacts, and monitor their purchases and movements.

Secondly, WeChat is also the main conduit for chat messaging within China itself, and through computer and human censorship, the Chinese government enlists tech companies such as Tencent to track what regular citizens say or do and punish them accordingly. We saw this happen recently when many Chinese were permanently locked out of WeChat’s social functions after sharing photos of a protestor on Beijing’s Sitong Bridge.

Finally, post-Covid, WeChat is one of the gateways hosting China’s health code, which as we described above, has helped to spread real-time surveillance across China.

Joyce Chan: One example of China expanding its surveillance systems overseas can be seen in Uganda. The book highlights the intricate involvement of Huawei in the country, which worked in favor of Uganda’s president Yoweri Museveni — using facial recognition tech, for example, to crack down on dissent. Can you elaborate on why it is in China’s interest to export these surveillance technologies to other countries, where China knows it might get little political gain in return?

Josh Chin: There’s a narrative out there that China wants to spread its model around the world. We think that’s too simplistic. China’s model is hard to replicate – a fact that the Communist Party likes to point out from time to time. There just aren’t that many countries out there that can combine vast amounts of data with cutting-edge technology, a robust economy, and a large, relatively competent bureaucracy.

So why export these technologies? First, it’s lucrative. Chinese surveillance companies, like companies everywhere, want to make money, and there’s a huge demand out there for what they’re selling. Second, it serves the Communist Party’s purposes for there to be a large number of governments around the world using surveillance technology to exert social and political control, even if they don’t do it as effectively as China does. The point is to make it normal.

Joyce Chan: How do you see this trend of China’s digital expansion developing in the future, with regard to Xi’s ambitious plans for the Belt and Road initiative, and building alliances in the Global South?

Josh Chin: The Belt and Road Initiative seems to have lost its way in recent years with so many projects getting mired in financial problems, but the tech-focused elements of it – otherwise known as the Digital Silk Road – are still going strong. China appears poised to increase its influence in the Global South through digital surveillance and other tech infrastructure programs – though recent U.S. moves to cut off China from access to top-end chips could undermine that.

Joyce Chan: A very interesting chapter of the book delves into the US situation and raises serious questions about the ethics and human biases in the adoption of facial recognition technology by police authorities. If a high-profile court case were to take place in China against the government, similar to where public defender Kaitlin Jackson sued the NYPD for the wrongful conviction of an innocent man using facial recognition, do you think it could shake up the people’s trust in the digital surveillance system and trigger wider resistance against privacy intrusion?

Liza Lin: The “ifs” loom large here. If such a case were to be filed in China, and if the Communist Party respected the rule of law enough to let it proceed, would it trigger resistance to state surveillance? Perhaps. But there’s so much corruption and caprice and human error at the local level in China, you might find people are comforted by the notion of rule by algorithms, regardless of whether they have bias baked into them.

Joyce Chan: How is the Chinese government managing to balance civil discontent that stems from rising awareness, and skepticism against the pervasiveness of digital surveillance — especially in the wake of individual protests that have sprung up in response to city-wide lockdowns across the country and the denial of human rights during the Covid-19 pandemic?

Liza Lin: Before the arrival of the Omicron variant, most Chinese people we talked to seemed generally happy with the surveillance state. Whatever privacy sacrifices it entailed, the system had prevented a huge number of deaths and made it possible to live some semblance of a normal life. Now it’s different. Omicron moved too fast for the surveillance system to track, so the government started using its technology to enforce mass lockdowns instead. That cratered the economy and led to a surge in public outrage over access to basic necessities like food.

You saw that frustration bubbling over with a protest in Beijing last month – just days before the 20th Party Congress – in which someone publicly described Xi Jinping as a traitor and called for him to be removed from power. It was remarkable that anyone could pull off that kind of a stunt in Beijing in this era. But the fact that a small protest drew so much attention is also a testament to how much control the Communist Party exercises over Chinese society. The Communist Party wants Chinese people to be happy, but it now has a whole new set of tools to maintain control even when they aren’t.

Joyce Chan: China’s Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) was passed in 2021. It is reportedly based on the EU’s GDPR from 2018, but up to now it looks like China lacks the enforcement to make it an effective law. What value do you see in the PIPL?

Liza Lin: PIPL was at least in part an attempt by the Party to deal with a real problem in China. Data leaks by telecom companies, internet firms, banks – you name it – are rampant in China, and people are angry about it. Under the PIPL, companies and certain state agencies have grown more cognizant of the need for cybersecurity and are held accountable for losses of data. What we found interesting was how China redefined the notion of privacy to focus the onus of the law on Chinese companies, avoiding penalties on data collection and use by the state. The law gives an exception for data collected for the purposes of national or state security, which indicates little will to change on that front.

Joyce Chan: Is there a point when citizens in China know full well that privacy infringement is an accepted reality under the rule of the CCP?

Josh Chin: There’s never really been a presumption of privacy in China, particularly when it comes to the government. You do see some incipient pushback against state surveillance, mostly in the biggest cities. That appears to have grown during the pandemic with stories of local officials using Covid surveillance tools for other purposes, like stopping protests. But it’s hard to say where that will go.

Prior to Covid, the Communist Party had done a good sales job for state surveillance in wealthy cities like Hangzhou, where you have AI-powered camera systems flagging illegally parked cars and automated traffic systems that help ambulances get to hospitals faster.

If Xi Jinping can find a way out of the zero-Covid quagmire, people might go back to their algorithmically streamlined lives and forget about their current frustrations. If not, then you’ll probably see the hard edge of surveillance being used more and more, and generating more resistance.

Joyce Chan