The clacking of keyboards; a cacophony of ringing telephones; and the distant whirring of a printing press: such are the sights and sounds of the newsroom in the public’s imagination. Outdated though these may be, they still reveal the enduring priorities for any journalistic organization: writing, news gathering, and publishing.

So where does that leave a group like China Daily USA, one of the key overseas bases for the English-language daily newspaper published by the Chinese Communist Party’s “Central Leading Group on Foreign Propaganda” (中央对外宣传小组)? According to its latest filings to the US government, the paper makes no profit, spends little on reporting, and outsources printing to major American newspapers in the markets where editions are distributed.

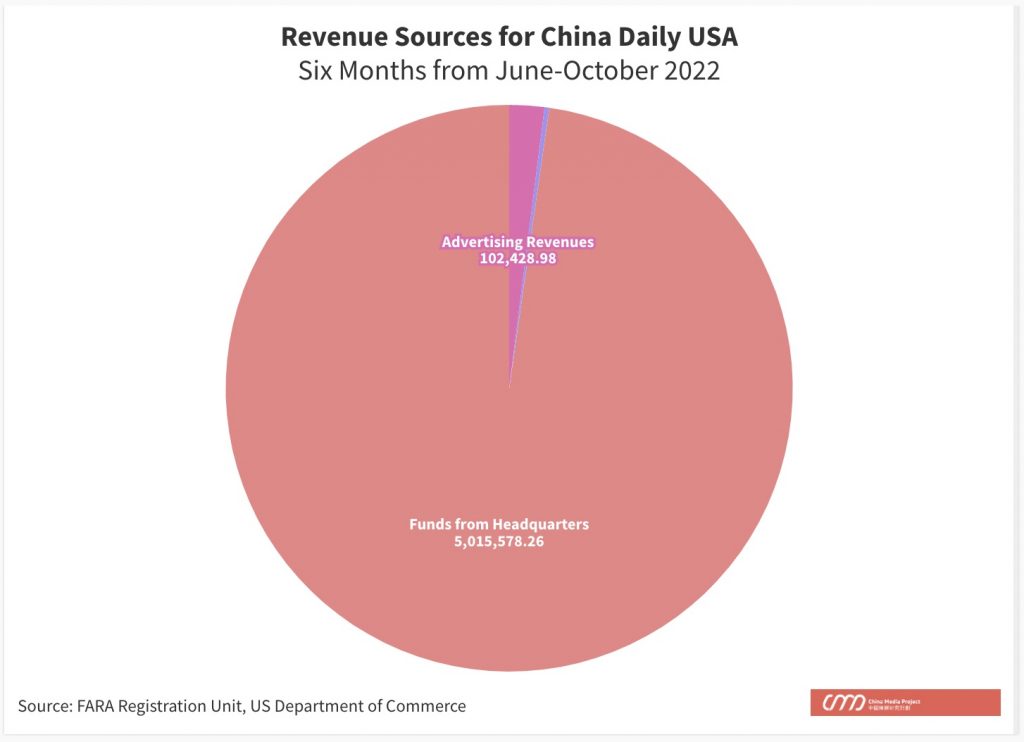

Between June and October 2022, China Daily USA brought in just over 102,000 dollars in advertising profits and a mere 13,000 dollars from subscriptions. The lion’s share of “revenue”— about 98 percent—came in the form of a handout totaling over five million dollars direct from China Daily headquarters in Beijing. For perspective, subscriptions and advertising accounted for 67 percent and 23 percent of revenues for The New York Times, respectively, in 2022, according to the latest annual report from the paper of record.

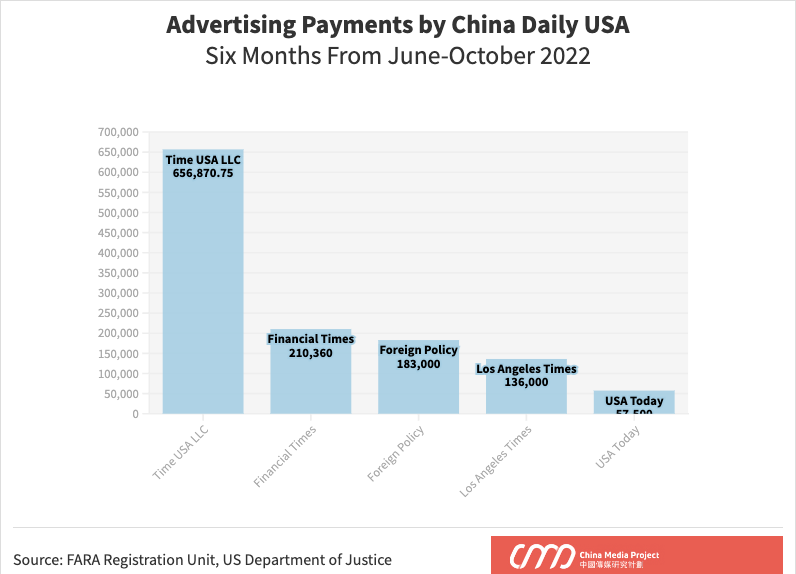

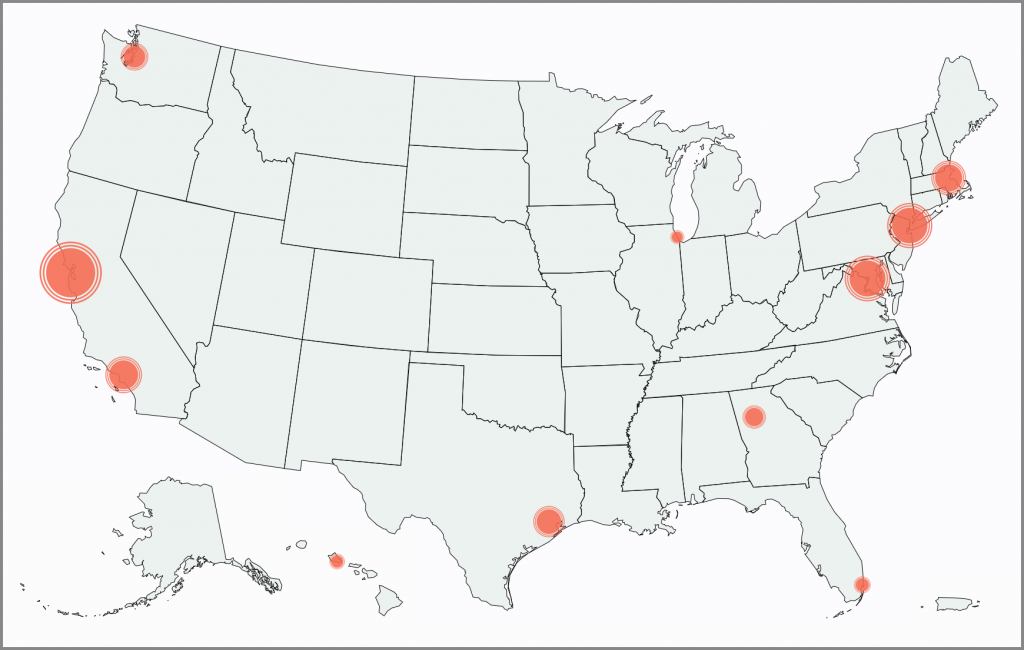

During the same six-month period, China Daily USA spent 604,974 dollars on payroll expenses to its stateside staff but well over twice that amount on “advertisement expenses” paid out to publications including TIME, Foreign Policy, USA Today, the Financial Times, and the Los Angeles Times.

This is a staggering amount to spend on advertising in an industry generally expected to make money from advertising. The picture gets more curious when one considers how the ads China Daily USA buys are designed to masquerade as news.

Most if not all of the payments to major US newspapers labelled as advertising in the latest filing would have paid for the printing and placement of the news-like “China Watch” supplement — eight pages of flattering coverage of the Chinese leadership and its policies designed to pass as legitimate reporting by virtue of its insertion inside the pages of trusted US news sources. While these supplements are labelled as “advertisements” by the host papers, it is left to US readers themselves to recognize them for what they are: state-sponsored propaganda.

While the government’s Information Office — the preferred global face for the “Central Leading Group on Foreign Propaganda” — has explicitly stated that the paper is “one of our most important tools in carrying out external propaganda,” China Daily has maintained the fiction that it is about factual reporting. In its 2014 media kit, the newspaper called itself simply “a global media with an Asia focus.” It referred to its advertising relationships with foreign newspapers for the “China Watch” supplement as “partnerships.”

In the global development section of its official website, China Daily boasts that “China Watch” reaches 4 million “high-end readers” through its “diversified cooperation with over 40 media organizations worldwide, including The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The Daily Telegraph, the Guardian, etc.”

But all of these “high-end” publications have since stopped accepting sponsored content from the Chinese government, with these transactions coming under greater scrutiny from authorities and readers who have felt deceived by the content’s presentation. The deals have generally been rescinded quietly and without comment by the papers involved. But when a group of major Australlian newspapers pulled out of the agreement in 2020, political editor Chris Uhlmann said he found it “extremely disturbing […] that Communist Party propaganda has the apparent endorsement of an Australian media organization.”

Details of the ins and outs of China Daily USA are publicly available thanks to the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), which requires anyone acting on behalf of a foreign government to register with the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and file public reports disclosing their budgets and expenditures.

After languishing in obscurity for decades, a diplomatic furor erupted around the World War II-era law in 2017 when the Trump administration required journalists with Chinese state media in the US to register as foreign agents. A report to Congress accused Chinese state media entities of involvement in spying and propaganda and recommended their US-based staff be required to register as foreign agents. China Daily has been designated as a foreign agent since 1983, although only its top executives had been obligated to individually disclose their work for the publication prior to this point, and before 2012 itemized financial statements for their “China Watch” advertisements were not provided to the DOJ.

Australia introduced its own Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme Act, modeled on FARA, in 2018, while in the United Kingdom, a Foreign Influence Registration Scheme has been introduced to Parliament through an amendment to the National Security Bill. Blind spots remain in some regions such as Europe but are also being eliminated elsewhere in response to growing concerns about Beijing’s influence. After intelligence reports of Chinese election “meddling” were leaked earlier this month, Canada opened a public consultation on its own version of a foreign influence transparency registry.

Hardening attitudes toward Beijing clearly have not been stymied by the millions spent to bolster China’s image through state-sponsored content like “China Watch.” US perceptions of China have fallen off a cliff over the past four years, with a record-low 15 percent of Americans viewing China favorably in the latest Gallup polling—19 points lower than the lows hit during the aftermath of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre.

With nearly all of China Daily USA’s inflow coming directly from the Party’s Propaganda Department and the vast majority of that ending up in the coffers of publications still willing to promote their message to potentially unsuspecting readers, how should one characterize the nature of this organization?

Their revenue sources make it clear they are not a viable business. How these revenues are then used shows they are not primarily a journalistic operation, either. If the skeuomorphs of the American newsroom are the mechanical keyboard and rotary phone, China Daily USA’s can be imagined as a deluge of cash and coins gushing noisily into a funnel, never to be seen again.