The enduring zeitgeist of Chinese “wolf warrior diplomacy” has created an atmosphere wherein nationalistic outbursts and calls for retribution are not only welcome but rewarded. But as Shanghai TV personality Zhou Libo recently discovered, not all calls to relive national glory are welcome.

On the eve of President Xi Jinping’s first state visit to Moscow since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the stand-up comedian and China’s Got Talent judge was banned from social media platforms Weibo and Toutiao for suggesting in a post that Xi’s “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” should include recovering land ceded to Russia in the 19th century. While calls to “take back” other lost Qing possessions like Taiwan are staples of Chinese nationalism, Zhou’s case shows that such revanchist rhetoric gets a frosty reception on the country’s Siberian frontier.

Despite the trembling induced in some Western observers by the sight of Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin gliding toward one another in the Kremlin’s gilded halls, censors have had their work cut out for them keeping the bad blood between these two on-again, off-again rivals from bubbling to the surface.

A Most Unequal Treaty

In what has become known as the Amur Annexation, the Qing court ceded over one million square kilometers of land along its northeast frontier to Tsarist Russia between 1858 and 1860. Foisted upon a desperate dynasty as it was ripped asunder by the Taiping Civil War and assailed by Britain and France in the Second Opium War, the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and the 1860 Convention of Peking were two of the most egregious of the infamous “unequal treaties” that Beijing was compelled to sign with belligerent foreign powers.

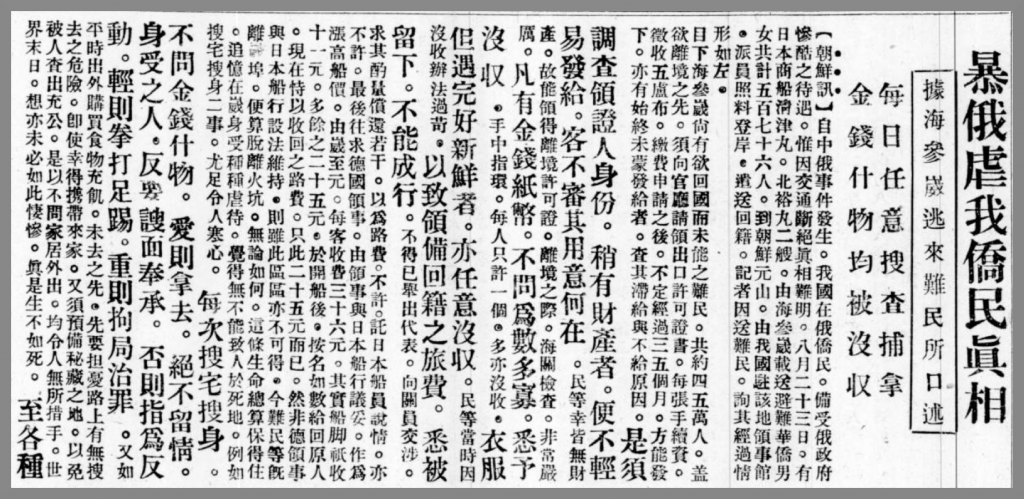

Qing territorial losses in these treaties were 12,700 times that of the original unequal treaty ceding Hong Kong Island to Great Britain in 1842. At a time when wars were decided by sea power, it also completely sealed off China from the strategic Sea of Japan. On the ground, the integration of these newly Russian territories was a chaotic and often bloody process: As many as 5,000 Qing subjects were killed in the 1900 Blagoveshchensk Massacre when local Russian authorities, fearing a spread of the anti-foreign Boxer Uprising, forced them to cross the border at the Amur River, with most drowning in the attempt or being cut down as they tried to flee. Later under Stalin, thousands of ethnic Chinese living in the Russian Far East were forcibly deported, in many cases to forced labor camps in the Arctic.

These incidents are not entirely forgotten but rank low on the Western- and Japanese-dominated pantheon of national humiliations used to boost patriotism and bolster regime legitimacy. Whereas the retrocession of British Hong Kong and the taking of Taiwan — two much smaller possessions ceded in Qing-era unequal treaties — are considered sacrosanct milestones for the “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation,” the area known now as Outer Manchuria is politely overlooked.

One consideration may be how the Amur Annexation undermines a key pillar of nationalist storytelling: Far from immutable entities with borders unaltered “since ancient times” (自古以来), the Qing and Tsarist domains were contemporaneous, competing imperial projects that experienced rapid expansion in the modern era.

Long before Royal Navy gunboats steamed up the Pearl River Delta, Qing officials signed the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, fixing the inter-imperial border with the Tsardom as its eastward drive march across Siberia ran up against the nascent Chinese dynasty’s own push northward through the ancestral Jurchen homelands previously considered beyond the pale. The first treaty signed by the Qing with a Western nation, Nerchinsk was also regarded as an unequal one signed under military duress— but only by Russian accounts, in a dynamic that would later be reversed as the Qing declined and Russia shored up its position in the far east.

Taming Nationalist Discourse

It is hard to tell which drew censors’ ire more: Zhou’s invocation to reclaim Outer Manchuria or his criticism of Chinese who fawn over “Emperor Putin” and refer to Russians by the cringey moniker “the martial race” (战斗民族). “Why are there always some Chinese who inexplicably send such kind words to Russia?” the post asked. “Do you still see Russia as your father? Friendship is fine, but flattery is not.”

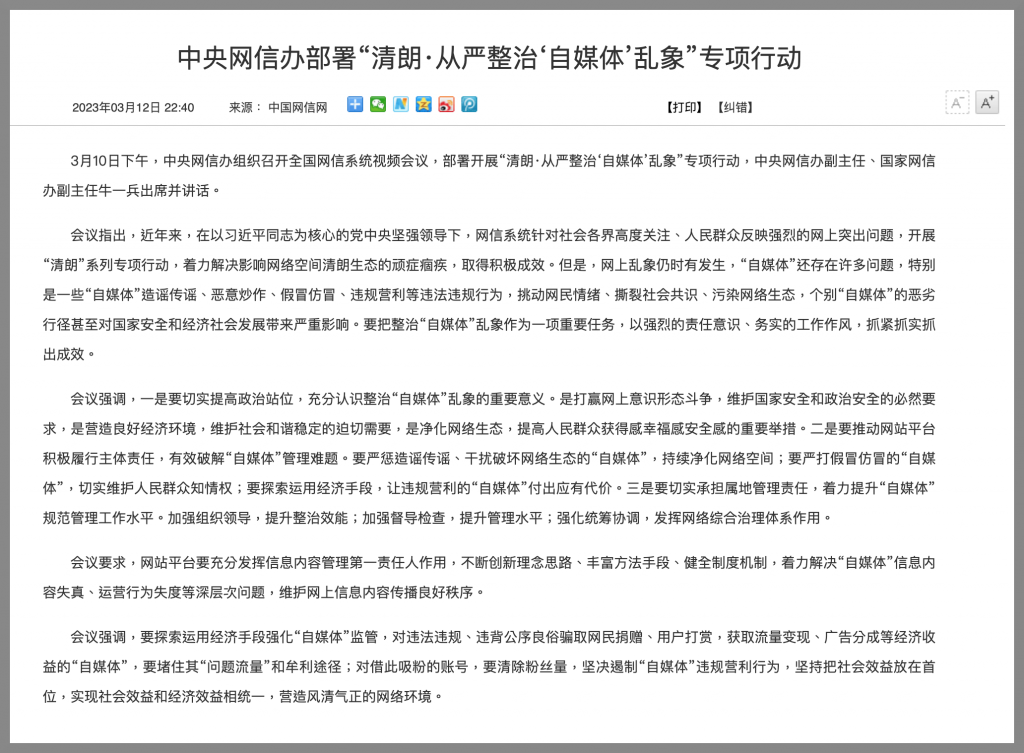

Zhou’s social media ban also came amid a renewed campaign by internet censors to “strike hard” against bloggers and live-streamers who post unauthorized content. On March 12, China’s Cyberspace Administration pledged to crack down on “rumormongering” by citizen journalists and to “win the online ideological struggle and maintain national security and political security.”

This episode is far from the first time that boisterous patriots have found themselves in the crosshairs after overstepping the mark. Anti-Japanese demonstrations that erupted in response to Japan’s nationalization of the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands in 2012 were eventually suppressed by riot police when property damage escalated and protesters began targeting the central government itself for not taking a sufficiently hard line against Tokyo. In 2021, a viral video calling for China to drop atomic bombs on Japan, should it come to Taiwan’s aid, was also removed from social media platforms — though only after it was shared by Chinese officials and amassed millions of views.

The window of acceptable discourse takes on very different dimensions depending on whether one is looking out over the East China Sea or the Siberian taiga. In the case of the former, talk of restoring imperial borders is familiar to the point that it has become mere background noise; the latter, however, provides a sobering vision of what happens when such “historical claims” are applied evenly and taken to their logical, bloody conclusions.

Reflecting and Projecting

Beijing’s increasingly asymmetric partnership with Moscow has rekindled speculation on whether China will push for the return of the vast tracts of land lost in the Amur Annexation. The punishment meted out to Zhou Libo for calling for just this is an indication of how unlikely such demands are to receive official backing, but the incident as a whole plays out like a satire of revanchism, exposing the fantasy of returning to a glorious past when what is and is not China’s was determined once and forevermore.

While history is often seen as what Song Dynasty scholar Sima Guang (司马光) termed a “comprehensive mirror” to better perceive the present, the unequal treatment allotted to the unequal treaties shows that the way we look back at the past is just as much a reflection of present exigencies. Sino-Russian partnership might have “no limits” according to the statement signed by Xi and Putin at their last tête-à-tête just days before the Ukraine invasion, but it does have a shelf life.