Xi Jinping signs an order for the Central Military Commission in January 2019.

For most writers and publishers in China today, opportunities for expression have dwindled in the face of overt and covert repression and creeping political hypersensitivity. As one long-time publisher summed up the tight squeeze recently: “You cannot say China is bad, and you cannot say that foreign countries are good.”

On the reverse side, this repression can be seen saliently in the return of the use of the press as a tool of personal political power. In the digital age, Xi Jinping may be unable to create, as Mao Zedong once did, a media monoculture to serve his narrow political ambitions. But in an echo of the pre-reform era, when Mao‘s supremacy was trumpeted through the so-called “Two Newspapers and One Journal” (两报一刊), Xi Jinping now dominates not just the headlines — but often, as in the case of the CCP’s leading theoretical journal, the bylines.

The same is true when it comes to books. Xi Jinping is far and away the most published Chinese leader in four generations. Not since the time of Chairman Mao and his pervasive “Little Red Book” has any leader’s voice commanded the presses so convincingly.

Consider: In yesterday’s edition of the People’s Daily, the front page was topped with two separate announcements of books published in Xi’s name. Before the so-called New Era, Xi’s predecessors could wait a full year, or as much as three years, for a single volume of any description.

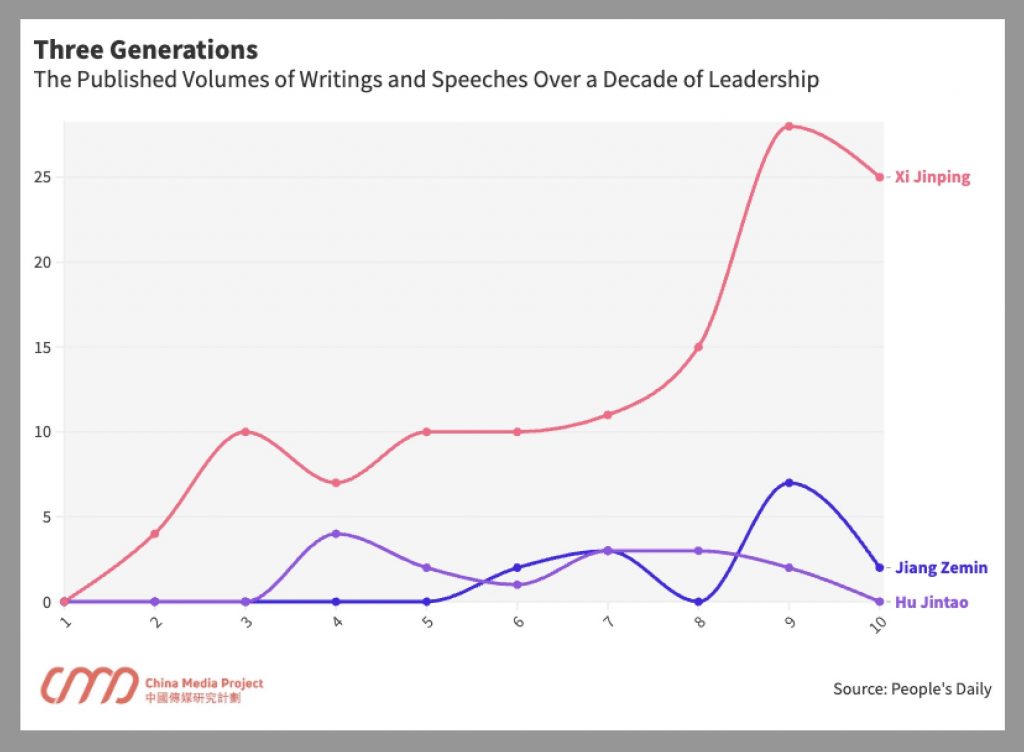

But exactly how does Xi stack up?

To find out, I made a headline search in the People’s Daily for the phrase “published and distributed” (出版发行), and then cross-referenced for mentions of Xi Jinping and his two immediate predecessors, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin — defining 10-year periods for each corresponding to their time in power. This allowed the isolation of instances of book publication related to each leader, including the release of special volumes, collected writings, and so-called “single-volume editions” (单行本), printed versions of major speeches and policies.

Xi Jinping is far and away the most published Chinese leader in four generations.

The gap I found between Xi Jinping and his predecessors in this arena is substantial. During his first decade in power, Xi published an average of 12 unique titles per year, all given rather prominent treatment in the People’s Daily. By comparison, Hu Jintao published just 1.5 titles per year. Jiang Zemin? Just 1.4.

Behind these numbers is also a clear transformation in the relationship between publishing and power. The bottom line: While the publishing of books and special volumes was not central to the exercise or consolidation of power for Xi Jinping’s predecessors, it has become a crucial means over the past decade to signal the centrality and essentialness of Xi and his ideas — and therefore the legitimacy of his grip on power.

Jiang Zemin: Book Dedicator in Chief

Jiang Zemin, in fact, was prolific in dedicating books by others, and in penning calligraphic titles for such works. Related news could be found in the pages of the People’s Daily several times a year through the 1990s. Jiang, however, was rarely ever the center of attention, and he and his ideas were never — so far as I could find — the focus of the books in question. More often, they dealt with past leaders such as Deng Xiaoping, sending a message of continuity rather than making claims of historic breakthrough.

Revealingly, Jiang Zemin’s peak year of more personal, legacy-related political publishing was 2001, the year ahead of the 16th National Congress of the CCP that would mark the appointment of Hu Jintao as general secretary. These volumes were about putting the final punctuation on Jiang’s time in power as he prepared to step aside, and about consolidating his contributions to the CCP canon.

In marked contrast to Xi Jinping, whose Governance of China was published during only his second full year in power, Jiang Zemin’s On the ‘Three Represents’ (论三个代表), the book dealing with his legacy phrase, was not published until October 2001, one year before he left office.

Hu Jintao: Anniversaries and Commemorations

Nearly all of Hu’s published volumes in 2006, one of his modest peak years (4), were anniversary commemorations — of the 85th anniversary of the founding of the CCP, and the 70th anniversary of the Long March. While the volumes were published in the name of General Secretary Hu, they were primarily about the milestones being commemorated.

The two other volumes published that year were not focused on Hu at all. They included a special volume of Hu’s reflections on his predecessor, Jiang, who had just published his collected writings, and Hu’s speech to commemorate the 120th birthday of Zhu De (朱德), the former commander-in-chief of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) who had died in 1976.

Hu Jintao peaked again in 2009 and 2010, with a series of published volumes commemorating various anniversaries, such as the one-year anniversary of the Wenchuan Earthquake, and the 30th anniversary of the founding of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone. But the only published volume with a clear relation to Hu Jintao’s political legacy was a single-volume edition (单行本) of his speech at a conference on the implementation of the Scientific View of Development (科学发展观), Hu’s banner term. This was already April 2010, as speculation simmered about possible successors, including Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang, or even, possibly, Bo Xilai.

Xi Jinping: A Power Tower of Books

With zero titles, the first full year of what would soon be touted as Xi Jinping’s New Era, 2013, was a slow one. But things picked up quickly the next year, putting Xi already on par with Hu Jintao’s historical publishing highs with volumes including a collection of his “important speeches” in June (followed soon after by translations into multiple ethnic dialects), and of course the Chinese-language edition in September of his Governance of China (习近平谈治国理政).

In 2015, I could find a total of 10 book titles, including special volumes, that gathered together Xi’s thoughts on various policy areas (such as governing the nation in accord with the law), as well as volumes that were plainly adulatory in nature. One example of the latter was Xi Jinping’s Allusions (习近平用典), which gathered together and explained 135 allusions — for example to classical literature — used by Xi in his official speeches.

Quite distinct from the past at this point, the focus was not just on meetings and special occasions, but on the inherent specialness of Xi Jinping. The Party-state media seemed to feed — and of course this was by design — on the character and cleverness of the general secretary, who according to the narrative had a genius for revolutionary ideas, delivered in language that could be down-to-earth, profound, or shrewdly historical.

Another example of this mode of publish-and-promote as a means of charismatic power construction was Xi Jinping Tells Stories (习近平讲故事), released in June 2017. The book, which, according to the People’s Daily (also the publisher) “selects more than 100 stories that embody his new concepts and philosophy for governing the nation,” again treated Xi as a font of Chinese wisdom (中国智慧).

From 2017 onward, following Xi Jinping’s formal designation as China’s “core” leader in the fall of 2016, the publication of Xi-related volumes steadily climbed, as can be seen in the graph further up.

The focus was not just on meetings and special occasions, but on the inherent specialness of Xi Jinping

Xi Jinping’s books consolidated his “talks” and “speeches” on virtually every topic imaginable — from his ideas on media and journalism to the economy, diplomacy, Party history, and even women and children. Some were “study outlines “ (学习纲要) as the country was gripped — or so it seemed in the CCP’s own headlines — by a fever of Xi study. There were special volumes for his official tours: Xi Jinping in Zhejiang; Xi Jinping in Ningde; Xi Jinping in Fuzhou; Xi Jinping in Xiamen.

In 2021, the year in the run-up to the 20th National Congress, there were 28 Xi titles promoted in the People’s Daily. Many of these were also foreign language editions, as the CCP sought to advertise Xi Jinping’s ideas, such as “building a community of shared destiny for mankind,” as visionary not just for China but for the entire world.

The dip in titles seen in 2022 is likely a short-term trend, like that previously seen in 2016. We can expect special volumes on Xi Jinping’s views on civilization, on “Chinese-style modernization,” on “whole-process democracy,” on “high-quality development,” and so on. The number of Xi volumes published and announced during the first five months of this year (11) already matched the total for 2019, and surpassed levels seen for 2017 and 2018.

Now in his unprecedented third presidential term, His Authorship will ensure that for years to come, there will be a veritable torrent of Xi Jinping-related books to publish — and not a drop to read.