In April 1989, as protests raged in Beijing and other Chinese cities, I dispatched a telegram to Qin Benli (钦本立), the editor-in-chief of the World Economic Herald in which I expressed my sympathy and support following his ouster from the outspoken 1980s-era newspaper. I was an active-duty officer at the time, working as a reporter for the People’s Liberation Army Daily, where I was in charge of the news desk. Though intended only as a personal message of respect and support, that telegram opened a Pandora’s Box of troubles.

A Herald Fan at the PLA Daily

Back in those days, we were all in the habit of referring to the People’s Liberation Army Daily simply as the PLA Daily. We referred to the World Economic Herald simply the Herald. Nearly all of China’s newspapers in the 1980s were “organs” directly controlled by the Chinese Communist Party. The Herald, however, was different. The paper had been launched in 1980 by the Chinese Society of World Economics (CSWE) and the World Economics Research Center of the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. It maintained its own independent financial accounting, and it was accountable for its profits or losses. This was all completely new.

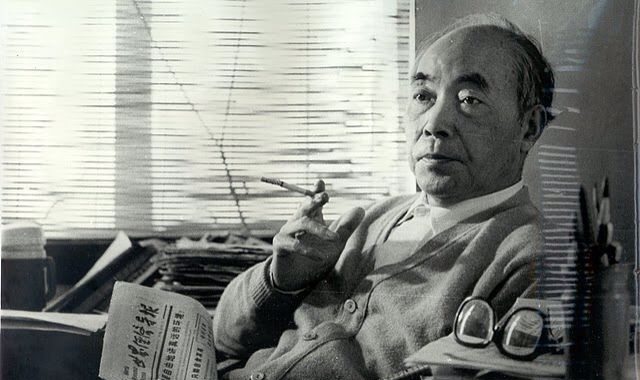

My attention was first drawn to the Herald in 1985. At the time I had just taken charge of the news desk at the PLA Daily, and my post came with a subscription allowance for various newspapers and journals, the likes of the People’s Daily, China Youth Daily, Red Flag magazine and Xinhua News Agency’s China Comment.

When I read the Herald for the first time, the paper astonished me with its clear support for reforms, its daring declarations and its fresh ideas. The impression it made on me was so profound that I can remember many of the headlines to this day: “Political Reform is the Guarantee for Economic Reform”; “The Chinese Communist Party Needs Democracy Like it Needs Air”; “Separation of Party and Government is the Crux of Political Reform”; “We Cannot Afford Not to Study the Political Reform Thoughts of Deng Xiaoping.”

My office would become a watering hole every time our copy of the Herald arrived at the PLA Daily.

The PLA Daily was conservative by contrast. But in the 1980s, even our paper was raked with the howling winds of media reform. The broader trend in the media at the time was to clean away the poisons of the Cultural Revolution and the vagaries of what we called jia da kong (假大空) — the “false language,” “bluster” and “empty words” that had surfeited Party media throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

Plenty of people at our newspaper were more open in their thinking.

In 1979, the PLA Daily had re-republished a lyric poem from Poetry Journal called, “Generals, This Cannot Be Done,” which criticized the demolition of a nursery school to make room for apartments for high-ranking military brass. One of our deputy editors was transferred from the paper for giving publication of the poem the green light.

Among younger journalists like myself, support for reform was strong. We interacted quite a bit with journalists from China Youth Daily and other publications known to push the bounds. We had a particular taste for bolder content.

In 1987, the World Economic Herald sparked a nationwide debate over the question of China’s international standing and the need for reform. The paper argued that the gap was widening between China and the developed world — that unless China was more robust in its pursuit of reform and development, it would be left out of the race entirely. It concluded that “the most urgent matter before the Chinese people remains the question of its ‘place in the standings.'” The debate rumbled across China and even drew international attention. It had never been clearer that the Herald was driving the agenda.

My office would become a watering hole every time our copy of the Herald arrived at the PLA Daily. I distinctly recall one issue that discussed the issue of “shareholding,” something completely fresh to us at the time. We had a lively debate at the office about what our own enterprises might look like if workers and ordinary people held shares.

Only once did I come close to meeting Qin Benli face to face. That was in 1986, when two of our reporters at PLA Daily were assigned to ride bicycles along the coast, filing stories on the way. When they reached Shanghai, I joined one of the reporters on a visit to the offices of the World Economic Herald. The idea was to pay our respects.

Unfortunately, Qin Benli was not there that day. We met instead with one of the paper’s deputy editors. So in the end, I would only knew Mr. Qin through the books of others, and of course through his work.

Revolutionary Newsmen

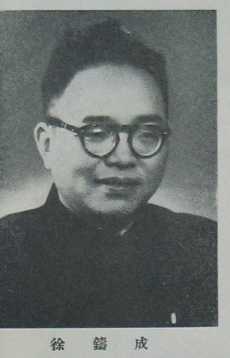

In the early 1980s, there was one book in particular that became a must-read for all of us working in the media. The book was News Anecdotes (报海旧闻), a memoir by former Wenhui Daily editor-in-chief Xu Zhucheng (徐铸成). During the Anti-Rightist Movement in 1957, there was a purge at the Wenhui Daily. Mao Zedong himself said that “the bourgeois-leaning tendencies of the Wenhui Daily must suffer criticism.” At the time of the purge, Xu Zhucheng was editor-in-chief and Qin Benli was deputy editor and secretary of the paper’s Party Leadership Group. While Xu was branded a rightist, Qin suffered only demotion.

Qin Benli was an old Party newspaper veteran. When the People’s Liberation Army took control of Shanghai in 1949, Qin and other noted Party journalists, including Ge Yang (戈扬), entered the city along with them. Qin Benli, it is said, even slept on the roadside with the soldiers at night. Qin Benli was tasked by the Party leadership with taking control of Shen Bao, China’s oldest modern newspaper. He also took part in the launch of the Liberation Daily, Shanghai’s official Party organ.

For a time, Qin was recalled to Beijing by Deng Tuo (邓拓) , the noted intellectual and journalist who committed suicide at the start of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, but was then the top official at the People’s Daily. Deng put Qin Benli in charge of economic reporting at the People’s Daily. But Qin later returned to Shanghai and the Wenhui Daily.

In 1989, this was all I knew about Qin Benli, but it was enough to inspire in me the deepest admiration for him. There were a handful of other capable and courageous journalists working within the Party newspaper world at the time – the likes of Deng Tuo, Hu Jiwei (胡绩伟) and Liu Binyan (刘宾雁). As an army reporter myself, I regarded them as greats worthy of emulation.

The Herald Falls

On April 15, 1989, Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦), the former General Secretary of the Party’s Central Committee, passed away in Beijing. Though a popular reform leader, Hu Yaobang had been ousted by Party conservatives in 1987, and Deng Xiaoping also bore much of the blame. The day after Hu’s death, a spontaneous public demonstration in the capital called for a reassessment of his legacy — and at the heart of this movement was growing displeasure with the conservative faction and with Deng Xiaoping.

On April 19, the World Economic Herald hosted a forum in Beijing to honor Hu Yaobang’s legacy. The forum was attended by noted liberals like Hu Jiwei (胡绩伟), Li Rui (李锐), Yu Guangyuan (于光远), Su Shaozhi (苏绍智), Yan Jiaqi (严家其), Dai Qing (戴晴), Chen Ziming (陈子明) and Zhang Lifan (章立凡).

In its April 23 edition, the Herald devoted five pages to coverage of the Beijing forum. The eulogies reported in the newspaper spoke not only of Hu Yaobang’s historic achievements, but also touched on Hu’s eventual political fate and what it exposed about the lack of rational mechanisms for succession within the Party. There was a focus in particular on the lack of democratic mechanisms within China’s political system. The consensus was a hope that authorities would resolve China’s political crisis by pushing ahead with political reforms.

I was away on a reporting trip while all of this was happening. But as soon as I returned to Beijing, the word on the street was that the Herald was in trouble. Shanghai’s Party secretary, Jiang Zemin (江泽民), had sent a special team to carry out a purge at the Herald, and Qin Benli had been stripped of his post.

The authorities ordered that Issue 439 of the World Economic Herald, which covered the Hu Yaobang forum, be recalled and destroyed. The news spread rapidly among journalists. And all of this was happening on April 26, the very same day that the People’s Daily ran its now infamous 4-26 editorial, “We Must Oppose Disorder With a Clear Banner.” The hard-line editorial, which argued that people with “ulterior motives” had used the Hu Yaobang commemoration to “spread lies” and “attack the leaders of the Party and the government,” enraged student demonstrators. The fuse of the June Fourth Incident had been lit.

A Personal Telegram

After the publication of the 4-26 editorial, journalists in Beijing were furious. They knew only too well that conservative forces within the Party had exercised strict control over the media since the Hu Yaobang protests, and had ordered the publication of completely fabricated news reports.

As soon as I returned to Beijing, the word on the street was that the Herald was in trouble.

On April 21, the People’s Daily had run a front-page report called, “Hundreds Surround Xinhua Gate and Create a Disturbance; Beijing City Issues Warning to the Malicious Instigators.” The news piece said there had been an attack on Zhongnanhai, the headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party:

Close to 300 students gathered in front of the Xinhua Gate and attacked Zhongnanhai. Some made inflammatory speeches, others shouted reactionary slogans, and still others threw bricks and soda bottles at police there to maintain order.

The report was not written (as advertised) by a Xinhua News Agency reporter. And it was a complete fiction. As journalists marched, shouting slogans like, “Don’t force us to fabricate lies,” and as news of the purge at the World Economic Herald spread, more and more journalists across the country pushed for media reform and greater freedom of expression.

Journalists in Beijing launched a joint signature campaign calling for Qin Benli’s reinstatement as Herald editor-in-chief, and one day I received a phone call from a colleague wanting to know whether I could help them gather signatures at the PLA Daily.

The request put me in a tough position. I was pained by the tragedy unfolding at the Herald, and I sympathized with its venerable editor-in-chief. But I was mindful at the same time of our special circumstances as serving military personnel – and I knew the unique nature of the PLA Daily.

In fact, the Cultural Revolution – the national tragedy whose horrors inspired the new endeavors of China’s media in the 1980s – had been abetted by the monopolization of speech and ideas by what we called the “two newspapers and one journal” – meaning the People’s Daily, the People’s Liberation Army Daily and the Party journal Red Flag. This media triumvirate had whipped up ideological fervor and aided the murderous politics of the day.

I knew that the political interference of the PLA Daily was part of the story of that tragic decade. And that hardened my conviction that the newspaper must eschew direct political involvement. In my view, a military newspaper like ours should strive to be a professional publication about military affairs. Surely, in the era of reform, a military paper with strong political overtones should be a creature of the past.

I wavered for several days over these questions. And then finally, on April 30, 1989 – it was a Sunday, I remember very clearly – I walked over to a post office in Beijing’s eastern suburbs and sent a telegram off to Qin Benli.

The telegram was personal. Never did I imagine that my colleagues at the World Economic Herald would transfer the message to a protest banner – or that they would hoist it up on Shanghai’s Huaihai Road along with messages of sympathy from 82 People’s Daily journalists. I never imagined either that the telegram would result in disciplinary action and dismissal from my PLA Daily post, as well as my discharge from the army.

A couplet, twelve characters on each line, my telegram simply said:

To you, the honor of history is granted unreservedly;

Pioneer of free speech in China, Qin Benli.