Telling Ukraine’s Story of the Russian Invasion

David Bandurski

Vita Golod

David Bandurski: Needless to say, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has been devastating and disruptive to people’s lives in your country. So first off, I just want to wish safety and security to everyone there. Our thoughts are with you.

Vita Golod: Thank you for your wishes. Right after the full-scale invasion, we got so many messages from our colleagues – sinologists from all over the world. Polish colleagues were conspicuous. Fifty-two Polish sinologists signed a support letter. Through the horror of the first weeks of the invasion, I can still remember the kind words of support. I appreciate this solidarity and the sincere desire to help.

David Bandurski: Maybe you could start off by telling us a bit about the Ukrainian Association of Sinologists, where you are Chairman of the Board.

Vita Golod: The Association was founded in November 2003. This year we celebrate our 20th anniversary. It is a non-government organization, a Ukrainian think tank focused on China studies and Ukrainian-Chinese relations. We unite more than 200 experts in different disciplines, like economics, international relations, political science, history, culture, linguistics, philosophy, literature, and so on. Most of us speak Mandarin and have a live-in-China background. Our goal is to promote the development of research on China in Ukraine and the development of Chinese studies, and we popularize modern knowledge about China.

LEARN MORE

David Bandurski: I know the war must have transformed the work that you and other sinologists and China experts do in Ukraine. Part of that for you has been building better communication. Could you talk about that?

Vita Golod: I was among those Ukrainians who did not believe that there would be a full-scale invasion. The next issue of the Ukraine-China journal was almost ready. We were going to dedicate it to the 30th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Ukraine and China. In one moment everything changed.

So, on the twenty-fourth of February, 2022, the day of the invasion — it was around 9:45 PM, I remember — I put a message in our social media group of interpreters about the idea of how our knowledge and expertise could be useful for Ukraine in wartime. All of us have WeChat accounts, and many of us have Weibo and Douyin accounts. It might work, I thought. We would just need more followers.

Every day we translated the official Ukrainian news and spoke Chinese to explain what was going on in Ukraine, replying to the comments. It was tough emotionally and needed a lot of time. We also organized live sessions with bloggers inside and outside China that have a large number of followers. We knew there were no Ukrainian media in China, so we hoped our work could at least present the Ukrainian view of events, which was hidden by Chinese authorities due to different reasons.

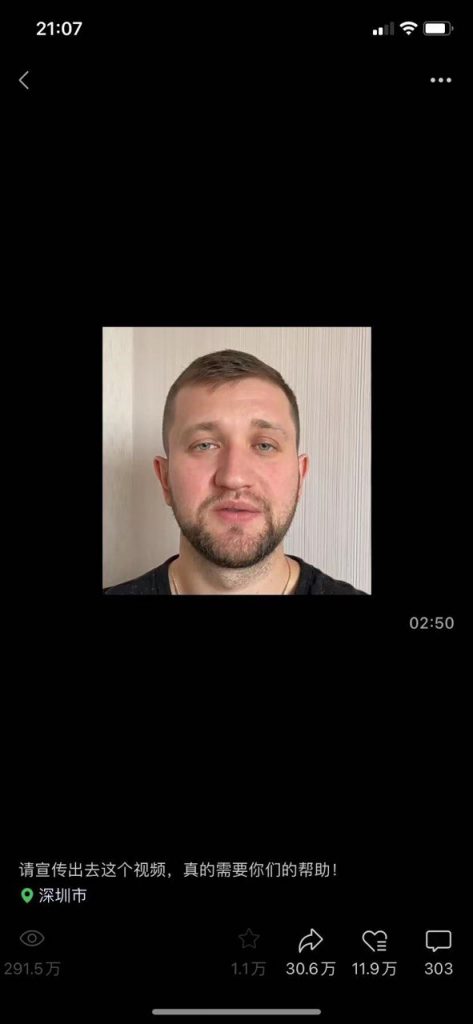

The day after the invasion, my colleague Kyrilo Chuyko posted a video in which he addressed the Chinese audience directly, expressing the feelings of people who were invaded, and who were experiencing fear and despair. It was a call for humanity.

David Bandurski: Did the video get a strong response?

Vita Golod: It went viral. The video was viewed by more than seven million people in just the first month of the war. Then, it gathered millions of comments and reposts on WeChat in China. That’s how this volunteering project started. About one-hundred people contributed their time and efforts translating news, making videos and captions, communicating with state and non-state organizations, and spreading hundreds of files through Chinese social media. We called the project an “informational defense of Ukrainian sinologists against Russian propaganda in Chinese social media.”

We did it voluntarily outside our main jobs, from all different parts of Ukraine — even from the occupied places like Borodyanka and Bucha, under the sirens and during evacuation. We have kept some of the products in an online archive on the association’s website. Our work can also be found on the Stand with Ukraine (烏克蘭需要你的支持) YouTube channel.

David Bandurski: I see that one of the projects the association has been involved in is a news and information website called Ukraine Online (乌克兰在线), which includes current reports about politics and society in Ukraine in the Chinese language. Could you tell us more about the thinking behind that and how it got started?

Vita Golod: The Ukraine Online platform was launched this summer. We were thinking about how to develop the volunteer activity we’ve done over the past year into a real long-lasting product. This project was organized by the Ukrainian Association of Sinologists and the Institute for Contemporary China Studies named after Borys Kurts, a Ukrainian historian, orientalist, and teacher. The editor-in-chief of the online platform is Yevheniia Hobova, a board member of our association. She’s a Ph.D. in linguistics, and is now a junior researcher at the A. Yu. Krymskyi Institute of Oriental Studies at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

As I mentioned before, there are no Ukrainian media in China, and Russian influence on Chinese state narratives is harmful to us. So, we have translated and promoted news about Ukraine in Mandarin daily, aiming to reach Sinophone audiences around the world. The website presents the Ukrainian view on events, and sometimes it is very different from the one available from the media inside China because of Russian influence.

There are no Ukrainian media in China, and Russian influence on Chinese state narratives is harmful to us. . . . It is essential to show the side of Ukraine that may not be visible in mainstream Sinophone media.

While the Russian-Ukrainian war is certainly the central topic for all world tabloids, we try to cover the events from various angles — including politics, social issues, the economy, culture, and the people’s personal stories. It is essential to show the side of Ukraine that may not be visible in mainstream Sinophone media. Also, we publish news on our Weibo and Twitter accounts. Soon we will be on WeChat too. The website can be opened in China without a VPN. So, we’d like more people from the Sinophone world to know about this platform. I hope this interview can help us reach a wider audience.

David Bandurski: Just now you mentioned the importance of personal stories. Is there any particular story that has stood out for you?

Vita Golod: Every family in Ukraine was touched by this war. Everyone has their own story of evacuation, loss, fear, and depression. So many of them. The personal stories of the people from Bucha, Kharkiv, and Mariupol, who lost everything and people they loved, every time made me cry. We have translated many of those stories.

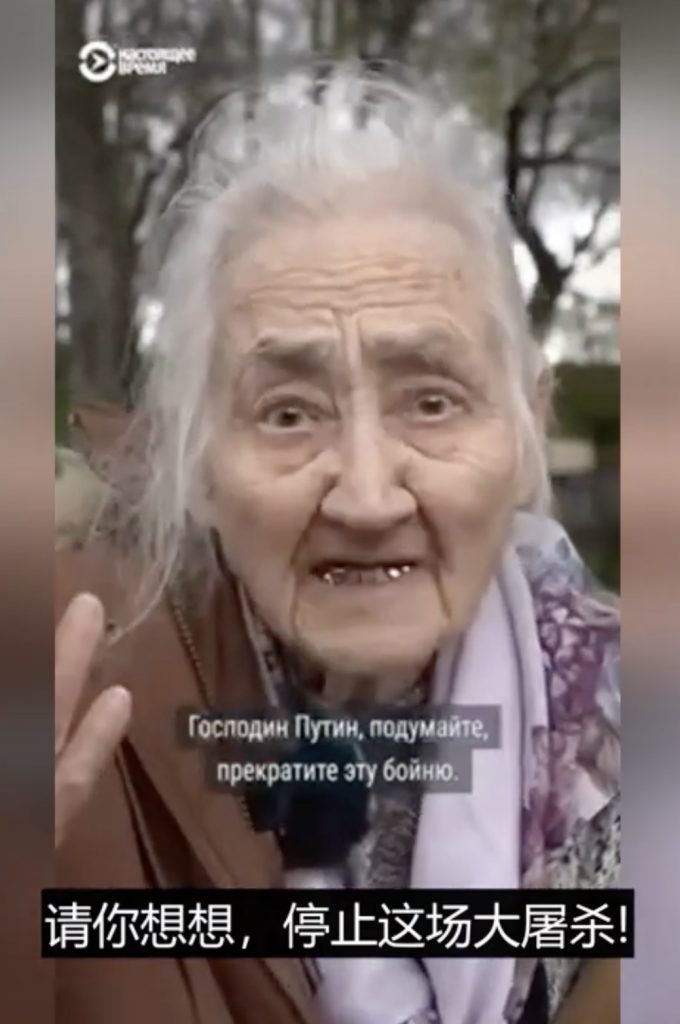

The interview with Elvira Borts, an old woman who narrowly escaped the horrors of Mariupol and survived, is a particular one. We shared her story, subtitled in Chinese.

I live in the Bucha area, but closer to Kyiv. My village luckily wasn’t occupied by Russians, even though they were very close and we heard the sounds of battles. I still remember how empty Kyiv was in March 2022, a city of 3.8 million citizens. I once passed through Khreschatyk Street, the main street running through Kyiv, in the middle of the day, and my car was the only one in both directions. I stopped at the red light and then realized there was no sense in it. I can’t even describe how sad I felt seeing abandoned streets, and house pets roaming around. The air was toxic.

Some of our colleagues have joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine. I’d like to mention Oleksyi Koval, the only Ukrainian professional journalist-sinologist, who reported from five Chinese Communist Party Congresses and worked with key Chinese media. His example deserves respect.

David Bandurski: Do you have any indication of how Chinese audiences have responded to these stories?

Vita Golod: When we went on WeChat with the stories, messages, or pictures, many new Chinese social media users started to invite us to the pro-Ukrainian WeChat groups. I was joined by 20 different groups with 500-700 users. My colleagues even more. We posted news there and let them share it on their channels. We never knew how many users were involved, but it was everyday work. Daryna Ustenko, another association member, contributed the most to this communication. After some groups were banned, our supporters created new ones. Some groups are still working up to now.

When we went on WeChat with the stories, messages, or pictures, many new Chinese social media users started to invite us to the pro-Ukrainian WeChat groups.

Another example of our work was a live session Kyrilo organized with a DW journalist in April 2022. Our colleagues also joined to share their feelings with the global Chinese-speaking community. We have kept the video with all the comments and wishes. It’s very informative.

David Bandurski: I noticed that you’ve also interacted with Chinese outside of the media. For example, you sat down with artist Xu Weixin (徐唯辛). Could you tell us more about that?

Vita Golod: A few months after the full-scale invasion, we realized that Chinese artists were the most supportive vocally of Ukraine. They helped us to promote true information about the war through their art, music, and poems. Some stories were published on our website. Deng Kangyan wrote several poems dedicated to Ukraine and our heroic people.

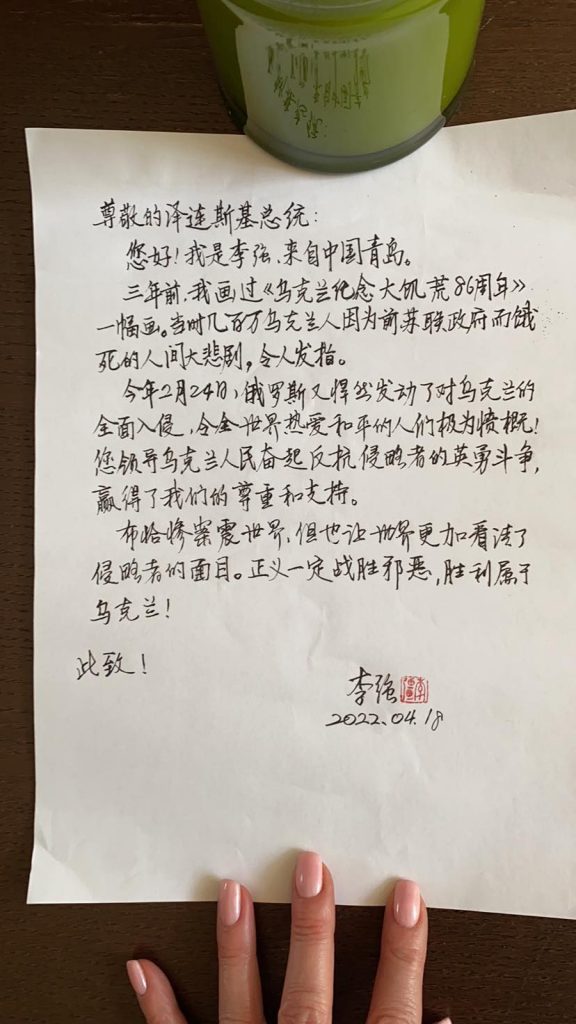

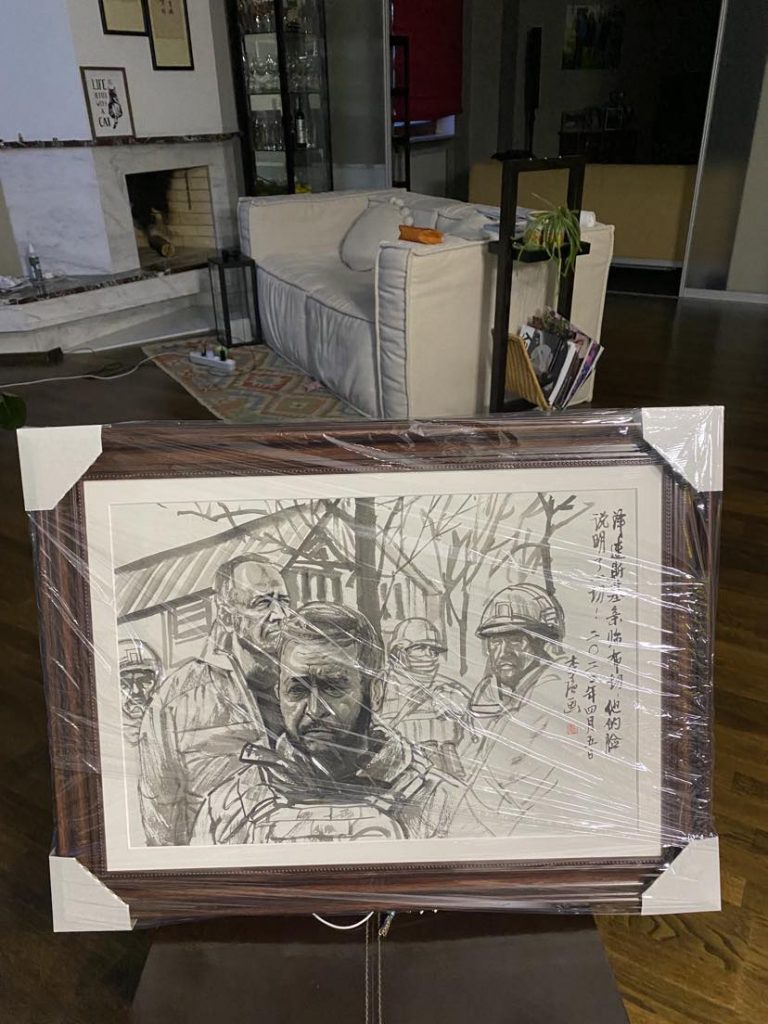

Li Qiang was the first artist who contacted me in April 2022. His WeChat group was the most productive in supporting Ukraine. He couriered to Kyiv one of his works — a portrait of President Zelensky, depicting his face after learning of the Bucha massacre, along with a letter to him. We passed it along with the portrait to the president’s office.

Xu Weixin is another example. He lives in the US now. Every day since April 15, 2022, he has sketched war scenes, the faces of politicians, soldiers, activists, and ordinary Ukrainians. Xu has created 539 works in total so far. The first time I interviewed him was in the fall of 2022 for an issue of the Ukraine-China journal. Then I visited twice his studio in New York. He said he would not stop his project until our victory, even though he got tired. We agreed one day that he would sketch my brother’s portrait as well. He is in Donbas now. Everyone who fights this war is a hero.

David Bandurski: How do you think the war has impacted the relationship between China and Ukraine? How do the people of Ukraine feel about China?

Vita Golod: According to opinion polls, Ukrainians have the most positive view of the responses to the invasion by Poland, the UK, and the US. That is completely understandable. The 32 countries that have shown neutrality in their UN votes toward Russian aggression can’t be considered favorably.

Ukrainians’ expectations of China playing a mediating role in the settlement of the conflict are gradually melting. China’s official neutrality, its peacekeeper image, and its rapprochement with Russia at the same time are confusing to Ukrainians. Our media pay attention to the role of China in this war, letting the Ukrainian audience hear the different points of view.

Ukrainians’ expectations of China playing a mediating role in the settlement of the conflict are gradually melting.

We have media freedom in Ukraine, which is one of our great achievements. But fact-checking and professionalism should take priority over clickbait. I would like to say, the number of non-professional comments on China has been rising in Ukraine, particularly since China announced its so-called peace plan. Sometimes, Ukrainian media, unfortunately, invite people to comment on China with zero relation to Chinese studies or even foreign policy. That provokes incorrect or even deliberately negative perceptions of the situation.

Since the invasion, President Zelensky personally and his office have taken on full responsibility for the foreign policy of Ukraine. He sees that China could play a role as a mediator in this war, and he very much welcomed the mission of China’s envoy, Li Hui, to Ukraine. This visit as well as the online meeting between Ukrainian and Chinese leaders were widely covered in the Ukrainian media and had a positive effect. Future bilateral relations will depend on China’s real actions on the peacemaking mission in Ukraine. For now, it’s ambiguous. I still truly hope Ukrainian foreign policy remains independent and won’t be designed somewhere in Brussels or Washington.

David Bandurski: In terms of Chinese coverage and discussion of the war, what do you and your colleagues observe today? Is there any change? And what would you say to the Chinese, and the Chinese media?

Vita Golod: I’d like to mention one important date. On April 11, 2022, the People’s Daily newspaper published the first big article about, as they call it, the “Ukrainian crisis,” in which it said that Ukraine was a pawn in the geopolitical game of the United States. Since then, China’s main narrative has remained unchanged.

Two days after the People’s Daily article, we published a response in three languages on our website — signed by the Ukrainian Association of Sinologists — and this was circulated through our international network. We publicly addressed intellectuals and policymakers in the Chinese-language world to make clear that the “Ukrainian crisis,” as they called it, arose as a result of Russia’s direct armed aggression against Ukraine. Ukrainians are fighting for their freedom and independence. Of course, we didn’t expect any reaction from officials in Beijing. It was our position, to call for fairness and justice.

David Bandurski: At CMP we looked quite a bit at the People’s Daily’s official treatment of the war, the “crisis,” and even how for months and months President Zelensky himself is never mentioned. But it’s also true that some Chinese media have tried to tell a slightly more nuanced version. We’ve covered that too. Assuming there’s room somehow for finding new ways to reach Chinese who are willing to listen, what other ways do you think your group can reach them?

One achievement we’re quite proud of in the past year is that we launched the Ukrainian Platform for Contemporary China. We succeeded in gathering prominent international sinologists for four round tables. I appreciate your contribution to one of those as well. Why was that important? We created a platform for professional dialogues on China, where Ukrainian audiences could see and hear well-known China experts, ask questions, and get some takeaways. It was important for us as well to share our concerns and find a consensus on sensitive topics. This platform helped us to create a network with different universities, think tanks, and media — including Chinese.

CMP COVERAGE OF CHINESE OFFICIAL REPORTING ON UKRAINE

I’m glad we are building relations with a new generation of Chinese scholars. Slowly, they have started to see Ukraine as a European country, not a part of the post-Soviet sphere. Last month an assistant professor from Peking University spent three weeks in Ukraine. We are preparing an article on how China sees Ukraine now versus then. As he said in one of our conversations — now I know there is a real war in Ukraine, not a Ukrainian “crisis” or a Ukrainian “issue.”

I hope more young Chinese researchers come to Ukraine. We are interested in a dialogue with young Chinese intellectuals. In fact, more Chinese journalists are coming to Ukraine now. One example was a group of reporters from CGTN who came in February this year. They spent two weeks in different parts of Ukraine. Not everything we did together or we recommended was published. But some episodes I’ve seen. They are really good. I know about CGTN’s Russian office, which shows the opposite news. Anyway, I was glad our colleagues were a source of help to show and tell the true story.

David Bandurski: As I’m sure you’re aware, the question of Taiwan’s security is often raised in discussions of the war in Ukraine. Sitting here in Taipei, I have to ask: Do you have any thoughts on that?

I spent a year of my life in Taiwan. That was a long time ago, and since then I’ve seen a crucial re-evaluation of Taiwanese identity. The tensions in the Taiwan Strait became a big media interest in Ukraine after Russia’s full-scale invasion. Some people have put both cases into a single basket. To clarify some of the related issues, I published an article with Dmytro Burtsev, another member of the Ukrainian Association of Sinologists, who is currently a postdoctoral research fellow of the National Chengchi University in Taiwan. We posted it to Ukrinform, a platform of Ukraine’s national news agency.

I hope more Chinese young researchers come to Ukraine. We are interested in a dialogue with young Chinese intellectuals.

Most Ukrainians, including journalists, have little knowledge of Taiwan. Sometimes, falsely overconfident “experts” and even officials use this as a manipulation tool, which is harmful to Ukrainian diplomacy, especially in wartime. When I mentioned in an interview that there are direct flights between Taiwan and China, and many Taiwanese factories are located in the eastern and southern Chinese provinces, the journalist doing the interview was genuinely surprised.

David Bandurski: Has the association been involved in outreach to Taiwan also to tell your story?

In July last year, actually, we successfully launched an advertising campaign in Taiwan called “Be brave like Ukraine.” This is a well-known project of Ukraine’s Presidential Office. Many cities worldwide supported it, including London, Rome, New York, Amsterdam, Washington, and Stockholm. In Taiwan, it became possible because of the funding provided by six private companies, organized by Dentsu Taiwan through Dentsu’s Ukraine office.

Getting it done took a long negotiation process. Many people and organizations were involved. After getting the permissions we needed, a member of our team selected fonts for the Chinese traditional characters. Then we started to communicate with different Taiwan institutions, including at higher levels, who might support us — but this failed. In the end, personal business contacts helped us to realize the project. All six Taiwanese companies received appreciation letters signed by Mykhailo Fedorov, then deputy prime minister and minister of digital transformation of Ukraine.

Anyone in Taiwan at the time might have noticed the big billboards, as well as stickers on taxis in Taipei, Hualian, and other cities. It even made the local news. However, I expected a bigger impact, to be honest. Anyway, I hope the Taiwanese will never face the same tragedy we have faced — I hope they never have to be brave like Ukraine.

David Bandurski