A New Shade of Chinese Feminism

Dalia Parete

Eva Liu

China’s nascent feminist movement has been one of the many victims of authorities’ crackdown on independent civil society and other perceived threats to Communist Party rule over the past decade. In recent years, the tightening of state controls and the introduction of restrictive laws on domestic NGOs has led to a new stage where digital platforms are more crucial than ever for feminist expression. Coupled with the rise of online nationalism, this has given rise to what media scholar Eva Liu of Ohio University calls “pink feminism” — an amalgamation of feminist discourse and ideals with the jingoism of China’s online nationalists, popularly known as “little pinks” (小粉紅).

Is this a true marriage of two ideologies traditionally considered at odds with one another, or just a way for digital feminists to get their voices heard without incurring the government’s wrath? Might “pink feminism” also contain some valuable kernels of truth about the origins of feminism in China? CMP researcher Dalia Parete spoke with Eva Liu to discuss these and other important questions.

Dalia Parete: I know it’s a bit ask, but could you briefly tell us about the history of feminism in China?

Eva Liu: I don’t want to oversimplify the complex history of Chinese feminism. Drawing from Chinese feminist historians, the first wave of Chinese feminism emerged at the turn of the 20th century, primarily led by male intellectuals and nationalists. This wave viewed the vulnerability of Chinese women as the root cause of the nation’s weakness and aimed to strengthen the nation by liberating its women.

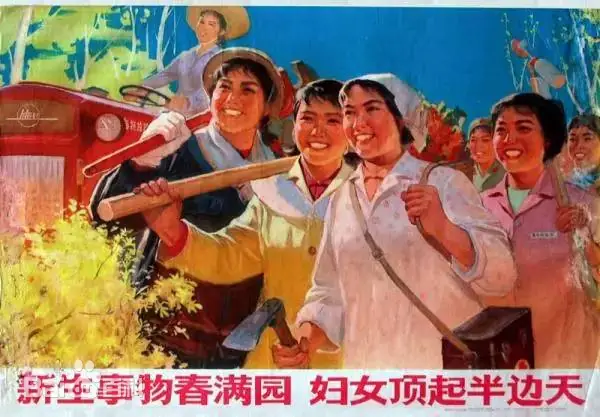

In 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) established a socialist regime, and I’m sure everybody is familiar with Mao Zedong’s famous slogan, “Women hold up half the sky.” During this historical period, public gender discourse emphasized the “sameness” between women and men, encouraging women to enter the public sphere of waged labor. Although this paternalistic discourse of women’s liberation never explicitly used the label of “feminism,” the educational level and workforce participation of Chinese women significantly improved then.

After the “Reform and Opening Up” in 1978, Western feminist theories began to enter China, and some Chinese universities started offering Women’s Studies courses. In 1995, China hosted the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, which not only facilitated more cultural exchange between Chinese and international feminist scholars and activists but also introduced the concept of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to China. After that, feminist NGOs began to spring up across the country.

In the 21st century, the Chinese government withdrew its support for local feminist NGOs, and the Foreign NGO Law, coming into effect in 2017, also prohibited local NGOs from receiving overseas funding. Since then, Chinese feminism has rarely mobilized through formal organizations, but individual expressions on social media become the primary force of feminist voices in China today, just like in many other countries.

DP: How would you define the relationship between feminism and nationalism in the context of Chinese digital feminism? Does this complicate traditional feminist movements?

EL: It is quite complex. In a recent article, I wrote how many Chinese anti-feminist influencers now stigmatize Chinese feminists as “Western hostile forces,” even if there is a clear lack of substantial evidence. At the same time, many gender-related discussions on social media are intersecting with nationalist sentiments. For example, during the Paris Olympics, numerous Weibo posts were celebrating the achievements of the 2021 Tokyo Olympics and the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics.

Many women have demonstrated their patriotism to the authorities by actively participating in nationalist campaigns such as the 2021 Xinjiang cotton controversy. These show that female citizens can be more “patriotic” than their male counterparts, who continue to watch NBA games after its executives showed support for the 2019 Hong Kong protests. This somewhat challenges the male-dominated nationalist narrative.

Many women have demonstrated their patriotism to the authorities by actively participating in nationalist campaigns.

It is important to avoid making hasty conclusions about whether these posters genuinely embrace both feminism and patriotism or if they are merely using nationalist discourse to “legitimize” feminist expressions in an increasingly restrictive online environment. The focus should be on emphasizing this “complexity,” both within digital feminist movements and in a broader context, including the Chinese setting.

DP: How do you think online censorship influences the strategies and discourse of Chinese feminists? Are there specific examples where censorship has hindered or inadvertently promoted feminist activism?

EL: Unfortunately, even some “moderate” feminists who do not directly criticize the state may still have their accounts deleted, be temporarily silenced, or be shadow-banned, meaning that fewer followers can see their posts in their feeds. It’s clear that there are double standards in how these platforms are managed, as online harassment against feminists often gets overlooked and online harassment against feminists is often tolerated.

In these circumstances, some feminists seek alternative platforms to express their opinions, which is not easy but worth trying. Others stay on mainstream platforms and confine themselves to a few “safe topics,” such as celebrating Chinese sportswomen.

Interestingly, when male users express dissatisfaction with certain content, feminists sometimes respond with nationalist rhetoric. Eileen Gu is a prominent example. Gu is viewed as a feminist for her empowering messages and also as a “nationalist” for renouncing her US citizenship and representing China, as reflected in the CCP’s official rhetoric. When male netizens criticize Gu — often over her dual citizenship — her female supporters frequently defend her by referencing official media coverage. These responses are particularly significant in today’s landscape, where alternative platforms are increasingly scarce.

DP: You recently co-authored a paper with Professor Han Ling on the phenomenon of “pink feminism” on Chinese social media. What do you mean by “pink feminism?”

EL: The term “pink feminism” has been circulating online for some time, and our work in this paper was to theorize it. It’s important to note that we do not define it as a feminist camp or identity, as very few people would call themselves pink feminists. Rather, the term is often used by those who are critical of it. We understand “pink feminism” as a practice, or more specifically a way of doing feminism in a highly restricted environment.

DP: How does this form of activism differ from more confrontational feminist approaches, and what are its potential strengths and weaknesses?

EL: I want to stress that pink feminism encourages young feminists to reexamine our indigenous history and corpus. In recent years, early Chinese feminists like Qiu Jin and He-Yin Zhen, along with socialist feminists, have been rediscovered by feminist communities.

Young Chinese feminists aren’t just passively studying Western feminist theories without thinking about local differences. They’re actively continuing the fight for gender equality, a goal that generations of Chinese feminists have worked towards.

This not only acknowledges the contributions of local feminist predecessors but also resists Western hegemonic interpretations of feminism. It is also an important step in countering the popular misconception that feminism is from the West. Young Chinese feminists aren’t just passively studying Western feminist theories without thinking about local differences. Instead, they’re actively continuing the fight for gender equality, a goal that generations of Chinese feminists have worked towards.

The limitations are quite clear: regardless of whether participants fully embrace nationalism, they are forced to avoid overt criticism of state policies. In other words, they end up compromising the critical edge of feminism just to increase their chances of staying safe.

DP: You suggest that pink feminism may reinforce existing power structures that feminists aim to dismantle. Can you provide examples of this?

EL: Yes, some pink feminist practices might indeed end up reinforcing neoliberal consumerism and state authoritarianism. When young feminists come across sexist ads, they usually take one of two approaches. One is through economic action — they’ll boycott the product, rally others to join in and look for alternatives. The other is more political — they’ll report the issue to the authorities. These actions show that women are using their power both as consumers and citizens. However, it’s important to remember that being a gender-conscious consumer often requires some level of class privilege.”

Participants need to stay reflective and not just accept government decisions without question. If the government doesn’t take action, it doesn’t automatically mean that feminists’ concerns are unreasonable. And if the government does take action, it’s crucial not to overlook the issue of procedural justice. Take Kris Wu’s sexual assault scandal in 2021 as an example. His social media account was deleted while he was under arrest, even though he hadn’t been convicted yet.

DP: How do you suggest Chinese feminists navigate the challenges of nationalism and engage with pink feminism without compromising their principles?

EL: In this paper, we want to highlight the internal diversity within Chinese feminism. We cannot label them as simply pro- or anti-state, and nor can we assume the superiority of feminisms that openly criticize the CCP.

For example, during the Olympics, we saw a lot of social media posts celebrating the achievements of Chinese female athletes. Even though female athletes have been winning more medals since China started competing, the sports fandom is still pretty patriarchal, and mainstream media often focuses more on male athletes. These social media discussions not only help boost the visibility of female athletes but also offer role models for young girls, encouraging them to be active and pursue fitness rather than aiming for unrealistic body ideals.

However, this “happy feminism” shouldn’t overshadow the need for feminist critiques of deeper structural issues, and it definitely shouldn’t be co-opted by state propaganda. While some critiques might struggle to get through on mainstream platforms because of censorship, we can look for alternative platforms that offer more freedom, even if that means losing some media visibility. Most importantly, even if the state or the neoliberal market seems to promote a certain type of feminism, feminists mustn’t let this biased form become the only version that’s seen as legitimate.

Dalia Parete