China’s Sentinel State

Dalia Parete

Minxin Pei

China Media Project researcher Dalia Parete spoke with Pei about the titular idea behind his latest book, The Sentinel State: Surveillance and the Survival of Dictatorship in China. Pei tells us about what makes the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) brand of mass surveillance unique, considering how it anticipates rather than simply reacts to dissent and how it combines the latest technology with grassroots mobilization and internalized censorship, involving citizens in the very machinery controlling them. It’s a system as old as the PRC itself, but one that has changed dramatically in the past few years and which will only continue to evolve.

Dalia Parete: What is the “sentinel state,” and how does it differ from the more familiar concept of the surveillance state?

Minxin Pei: In my book, I introduce the concept of distributed surveillance, highlighting how China conducts its surveillance distinctly. While all dictatorships employ repression, the most sophisticated ones, like China, lean heavily on preventive rather than reactive measures — essentially ex-ante repression versus ex-post repression. The real challenge lies in designing an effective system for this preventive repression. Should all surveillance responsibilities be concentrated within a single agency or distributed across multiple entities? Each approach has its trade-offs. For instance, if you go the route of a centralized agency like the Stasi [East German secret police], you invest heavily in a large bureaucracy that could ultimately threaten the ruling party itself.

On the other hand, China’s strategy involves decentralizing tasks horizontally across various security agencies, and vertically by incorporating civilian involvement. These civilians, while formally part of the security apparatus, take on key surveillance functions. This creates a unique system where surveillance is distributed and multifaceted, allowing the government to maintain control without the vulnerabilities that come with a single, centralized authority.

While all dictatorships employ repression, the most sophisticated ones, like China, lean heavily on preventive rather than reactive measures.

DP: Which is more important for this sentinel state — the technologies of repression or the human resources of state control?

MP: There’s often too much focus on technology itself. While it can be a useful tool, it is used by people. And let’s not forget that technology has lots of blind spots. It can accomplish many tasks, but if people implement countermeasures, technology becomes ineffective. For example, if someone wears a mask or a hood, facial recognition systems struggle to identify them. Similarly, if you hide your phone in a Faraday bag, the government loses track of your movements. There are lots of limitations to technology. This is why I believe the most effective approach combines human intelligence and technological resources. China has both advanced technology and a highly organized structure.

DP: What did the Covid-19 pandemic reveal about China’s surveillance capabilities?

MP: During the pandemic, China’s approach to enforcing lockdowns was truly remarkable, particularly in how it used cell phone monitoring. The most crucial part was the actual collaboration projects with private companies like Alibaba and Tencent, as they developed health tracking systems.

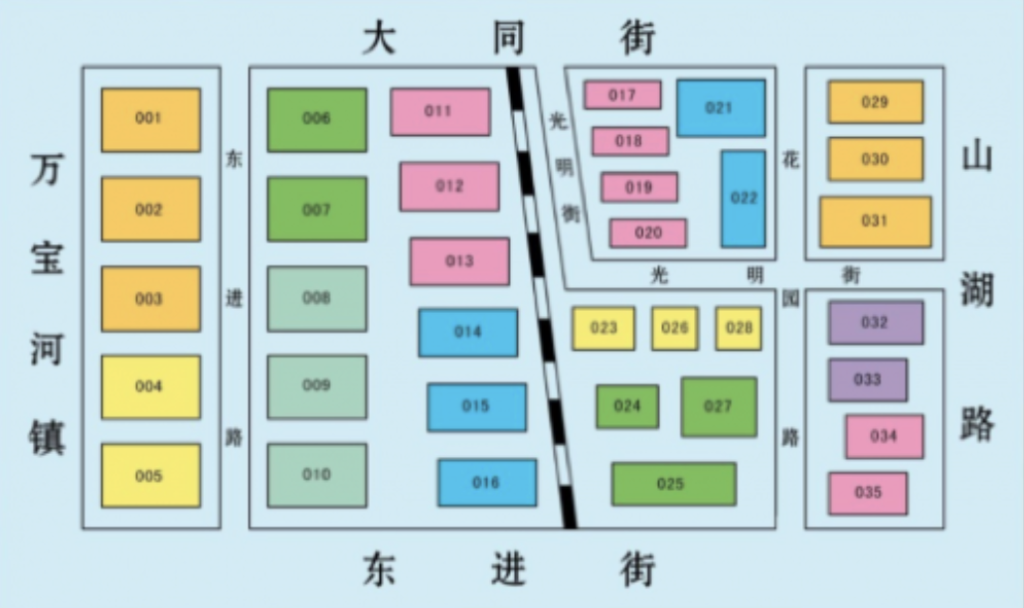

Another significant aspect was the use of so-called “grid management” (网格化管理), which is much more labor-intensive and human-focused than technology-driven. This approach proved to be quite effective during the pandemic. China implemented a system where communities are divided into several grids, typically comprising around 1,000 people or 300 families. Each grid is closely watched by an individual who not only monitors these families but also provides various community services.

To effectively lock down a community, you need active participants. So, those two elements — phone monitoring and grid management — played vital roles. Interestingly, traditional tools like facial recognition and video surveillance were not very useful during the lockdown since people were confined indoors.

DP: Would you say the pandemic was a trial run for China’s technological capabilities?

MP: Because of the uniqueness of the pandemic, it was a limited test. There was a lot of self-enforcement because people also did not want to get sick. So, during the pandemic, the government didn’t need to resort to heavy-handed coercion. About half of the population probably complied with regulations simply out of self-interest and a desire to stay safe.

DP: What role does the Chinese media, including state-run outlets, play? Are they part of the sentinel state?

MP: In this case, official Chinese media don’t play a significant role. Their primary function is to disseminate government-sanctioned messaging. I think that social media is the main target for surveillance because the government has a very sophisticated and effective way of monitoring what’s happening on social media. If a particular topic starts trending, they swiftly intervene to suppress it. There is a very good system in place in that sense.

In my book, I don’t focus on the output side of this — essentially, how the government employs censorship. One lesser-known aspect of China’s internet surveillance is how they monitor who is accessing the internet. They’ve created effective technology to ensure that anyone using the internet has their identity recorded by the authorities. This way, they maintain tight control over online activity.

DP: What lies behind the Chinese state’s paranoia and need for control?

MP: This system was developed in the aftermath of Tiananmen Square. This taught the Chinese Communist Party a very important lesson: they needed to be aware of what was happening in society. Like other dictatorships, the Chinese Communist Party is very fearful of dissenting voices, especially activists, because they need to deter the population from engaging in protests, in anti-regime activities. Most of the time, these activities can be led by a small number of activists. Because they set an example, they show the rest of the population that they are not afraid. To make sure this does not happen, the government relies heavily on surveillance. If somebody dares to challenge the Party’s authority openly, that person will be discovered and punished.

In my book, I discuss what I call “key individuals.” These are people who are subject to close monitoring by human assets and technological means. There are even “internet key individuals” whose online activities are closely tracked. Some of these individuals are restricted from accessing certain websites or services to further limit their influence.

DP: What do you make of China’s plans to introduce a national cyberspace ID scheme?

MP: From the Party’s perspective, the more control they can exert, the better. That’s their mindset. However, we also have to consider the law of diminishing returns. In this context, the additional benefits the Communist Party might gain from implementing a cyber ID are likely quite limited. Given how effectively they control the internet, I’d estimate they oversee about 95 to 97 percent of online activity. To capture that remaining two to three percent would require a substantial investment of resources, leading to high marginal costs that probably don’t yield significant benefits. You have to hire people to monitor. You have to actually harass people if you catch them. Then what if they keep posting? It will probably cost them a lot of manpower.

This feels excessive, especially considering that the party can quickly identify who is online. When you use home internet from state-owned providers, your IP address is already known. The same applies to your phone. Even in public places like cafes they have surveillance systems to track IP addresses. So why introduce a cyber ID? It seems largely unnecessary. Additionally, many people in China are already quite cautious about their online behavior, leading to considerable self-censorship.

DP: So why do you think these plans are being rolled out right now?

MP: Xi Jinping has been emphasizing a comprehensive approach to security. National security is not just about defense against external enemies but also maintaining social stability and cybersecurity. So, under that guideline, Chinese censorship agencies and domestic security agencies will ask, “How can we carry out the top leadership’s instruction?” So, they propose all kinds of measures, such as cyber IDs. From a bureaucratic perspective, this is a clear response to new directions from the central authority, prompting the bureaucracy to take action. When we look at the current circumstances, like the slowing economy, there’s probably more social unrest. There will be a lot more public dissatisfaction. The government aims to suppress expressions of this dissatisfaction and potential social unrest.

By introducing something like a cyber ID, the Party hopes to enhance self-censorship, as people will be afraid to express their dissatisfaction online. However, this approach might backfire. If individuals feel they can’t voice their frustrations online without repercussions, they may resort to more destructive means of expression. That’s why I believe this strategy may not be beneficial. Over time, this will also depend largely on the economy, as the Chinese security apparatus is primarily funded by local governments. If these local governments do not have the resources, both the human and technological components could suffer. They won’t be able to recruit more informants or maintain and upgrade their technology, which, as we know, can be quite costly.

By introducing something like a cyber ID, the Party hopes to enhance self-censorship, as people will be afraid to express their dissatisfaction online.

DP: Finally, what are the scenarios in which the sentinel state might break down?

MP: If the economy breaks down, it will be the first sign of trouble. You’ll likely see a degradation of the security system and a rise in public discontent. Another concern is the potential for corruption within the system itself. Those in charge of security wield significant power and have access to resources. Instead of using funds for informants or upgrading the system, they might enrich themselves, leading to better facilities and higher salaries rather than enhancing security.

Additionally, there’s the issue of overreach. The demand for security can seem insatiable, like a beast that can never be fully satisfied. This could result in unnecessary spending on resources — like an excessive number of surveillance cameras using the latest technology — when it may not even be needed.

Dalia Parete