Newsroom Standards in the AI Era

Tian Jian

Wang Feng

The advent of ChatGPT in 2022 sparked a global boom in generative artificial intelligence (AI). Its applications are rapidly expanding, and journalism is no exception. From AI-powered news anchors to assisted writing, editing, and transcription, image generation, and analysis of massive datasets, AI is now widely applied across every step of news production. Recently, newsroom-tailored AI consulting tools have emerged, aiming to promote “responsible AI use” among journalists.

In August 2023, numerous media organizations — including Agence-France Presse (AFP), the Associated Press (AP), European Pressphoto Agency (EPA), European Publishers Council (EPC), Gannett (the parent company of USA Today), and Getty Images — jointly issued an open letter calling for rules and responsible development principles for generative AI models. Soon after, the AP released its official AI guidelines, becoming the first major news organization to release AI use regulations for its newsroom.

In the Mandarin-language media sphere, Taiwan’s Central News Agency (CNA) and Public Television Service (PTS) published their own AI usage standards and guidelines in September 2023; The Reporter (報導者) , one of Taiwan’s top independent news outlets, followed with its own usage rules in July 2024. In China, the state-run China Media Group (CMG), the media conglomerate under the Central Propaganda Department, embedded political guidelines into its Interim Regulations on the Use of AI, introduced in March 2024, stressing that “adhering to correct guidance is always the foremost principle” and that “socialist core values” must be upheld regardless of technological development.

The AI-led transformation is impacting professional work cultures at some of the world’s oldest journalism outlets, including the Financial Times (FT), the British daily newspaper founded as a broadsheet in 1888. Like its English-language counterpart, the Chinese-language edition of the FT (FT中文网), broadly applies AI across its news production and distribution. It has launched its own chatbot and normalized AI integration into functions such as audio news readouts, newsletter production, image generation, and column translation.

FT Chinese editor-in-chief Wang Feng (王丰), who also teaches journalism at Tsinghua University’s School of Journalism and Communication in Beijing, has witnessed the AI wave in journalism firsthand. Over the summer, he spoke with Tian Jian (田間), the China Media Project’s sister publication on Chinese-language journalism and media, to talk about how FT embraces AI technology while safeguarding journalistic professionalism — providing readers with more valuable services.

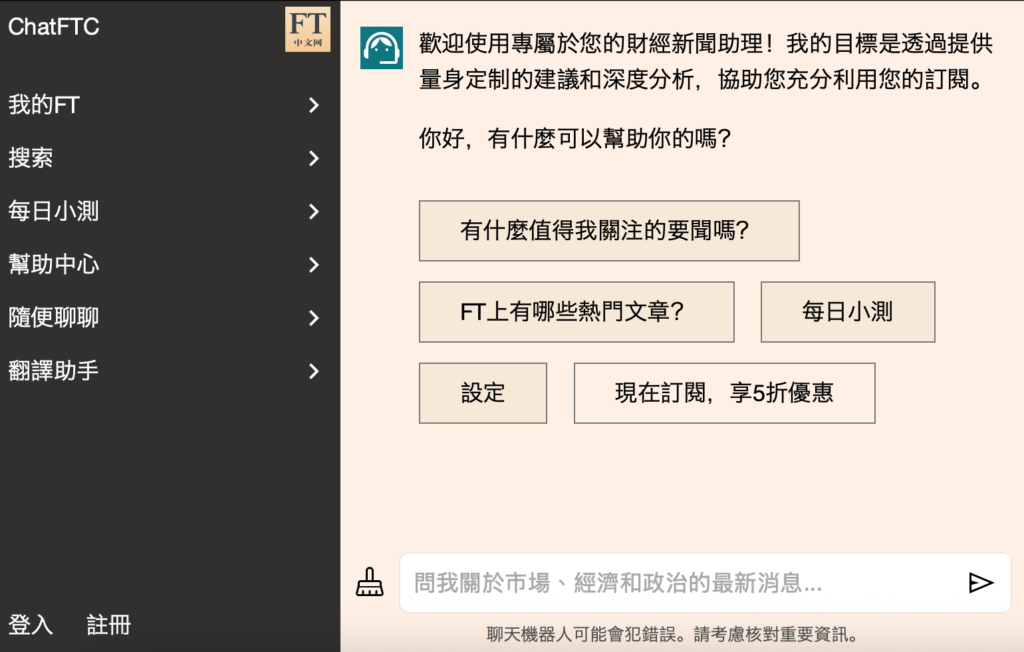

Tian Jian: FT Chinese makes extensive use of AI. From the reader’s perspective, the first thing that stands out is your dedicated chatbot, “ChatFTC,” whose name resembles ChatGPT. It acts as an AI financial news assistant for users. Could you share the process of the model’s development? What training data was used? And how have usage and reader feedback been so far?

Wang Feng: This wasn’t originally developed by FT Chinese. It’s a product created by the FT headquarters, where a technical team of over a hundred people built and pre-trained it. It’s based on the ChatGPT framework, but trained on FT’s news content. On that basis, we (FT Chinese) then retrained it again using our Chinese-language content.

Its special feature is that you can ask questions such as: what coverage has there been on this topic in FT’s reporting over the past year? What facts, what data? Give me a timeline, give me a long-term background introduction to this or that topic … In short, it allows an ordinary reader, beyond reading just one piece of news, to have a deeper experience, grounded in the FT news archive.

But I’m afraid it’s still difficult to completely avoid hallucinations. At least for us editors, the chatbot is still something of a black box. The tech team hands it to us after developing it, but we editors are not completely clear on how exactly they built and trained it, and to what extent it accesses the news database.

So we’ve explained to readers that this remains an experimental product. We hope it enhances their experience, but we cannot 100 percent guarantee accuracy. If someone needs reliable guidance for work or research, we recommend ultimately relying on FT-published articles as the standard.

Tian Jian: When did FT headquarters begin developing AI-related tools? Was there a delay for FT Chinese [compared to other newsrooms]?

Wang: FT now has a cooperation agreement with OpenAI. But in 2023 — before the OpenAI partnership — at the annual executive meeting at FT headquarters, all executives were required to immediately register for an Anthropic account and a Claude AI account. The idea was to press us to see firsthand how much AI had already advanced.

As FT executives, that was the first time we realized large language models had made such dramatic progress in text. Around the same time, the London headquarters began negotiating with AI companies, including Anthropic and OpenAI, and in 2023 and 2024, they began in-depth development. FT Chinese progressed in parallel — once HQ has built something decent, we can adopt it without delay.

Tian Jian: How are FT users currently using the AI financial news assistant “ChatFTC”?

Wang: Of course, we can’t see exactly what readers are doing with it. But the tech team can see how many people are using it, how much traffic it consumes, and roughly how frequently each reader engages. They regularly pass this data back to the editorial team.

But at present it’s more of an interesting novelty; the usage rate is not very high. One major issue is that ChatGPT is inaccessible in mainland China. Even for myself, though I’m based in Hong Kong, I have to use a VPN to access it. Readers in the mainland need to scale the firewall in order to use this tool, which is very difficult. It’s also limited to subscribers. So there are multiple levels of restriction, meaning perhaps only the most tech-savvy [mainland] readers who know how to successfully bypass restrictions end up using it.

Tian Jian: How is the readership for FT Chinese distributed?

Wang: Our primary market is mainland China, which makes up the overwhelming majority: 85 percent of readers are in the mainland. Hong Kong accounts for 5-8 percent, followed by Taiwan and Singapore, and then overseas Chinese readers in North America, Europe, the UK, Australia, and Canada. FT Chinese was originally created as a Chinese-language product geared toward mainland China. When we started 20 years ago, the idea was to translate FT’s English content into Chinese for those in the mainland who had very limited access to international information.

Tian Jian: From a reader-centric standpoint, when it comes to products like chatbots, has the team considered integrating DeepSeek? What experience does your team have with Chinese-developed AI tools?

Wang: This touches on the geopolitical regulatory problems with large AI models. Since our parent company (FT) is a British company, and has already signed a cooperation agreement with OpenAI, the company recognizes it as sufficiently safe. The current company policy is to mainly use OpenAI’s products for AI applications. On top of that, because cross-border data flow issues under the EU’s GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) affect China, the UK, and Europe, even if FT Chinese wanted to collaborate with DeepSeek, it’s unlikely that headquarters would approve.

The current company policy is to mainly use OpenAI’s products for AI applications.

Our staff currently doesn’t have very strict limits on using Chinese tools. But when transcribing interviews, if sensitive information is involved, can we upload it to iFlytek’s servers? If colleagues are concerned, we discuss it together. My advice is: if it’s sensitive, don’t use iFlytek. Transcribe it manually. Luckily, most of our content doesn’t reach that level of sensitivity.

My colleagues and I use DeepSeek, Tencent Yuanbao, and Doubao quite a bit. We find DeepSeek’s most significant flaw is hallucination: it often presents fabricated information in a serious manner. This happens quite often, more often than with Perplexity or ChatGPT. So I personally rarely use DeepSeek for interviews or content-related work. That said, its proficiency in Chinese is much smoother, so sometimes I’ll use it to rewrite headlines or write summaries — but I always re-read to ensure accuracy.

FT recently began conducting surveys to better understand which AI tools everyone is using. I suspect the next step is to formulate a strategy to prevent possible data or privacy issues. We are making up the rules as we go. Internal management policies are continuously being updated.

Tian Jian: Does FT headquarters currently have a set of guidelines or rules for AI use?

Wang: They have some basic codes of conduct, and employees are required to undergo regular annual training and internal examinations. But enforcement is difficult — no company can really monitor every single task each employee does.

In daily work, the way these principles are applied comes down to individual judgment. If you’re unsure about something, you talk to your manager for guidance. If the supervisor can’t decide, it escalates to consultation with a legal counsel or an in-house lawyer.

I often discuss these issues with my colleagues and share my own AI usage experiences with my team. The most basic principle is: even if AI generates something, you are still 100 percent responsible for its accuracy. You must verify everything it tells you.

Right now, most people are still exploring how to use AI. Few are thinking far enough about how to ensure AI outputs comply with all professional, ethical, and legal standards. Even just ensuring 100 percent accuracy is already quite difficult. We are still in the very early stages.

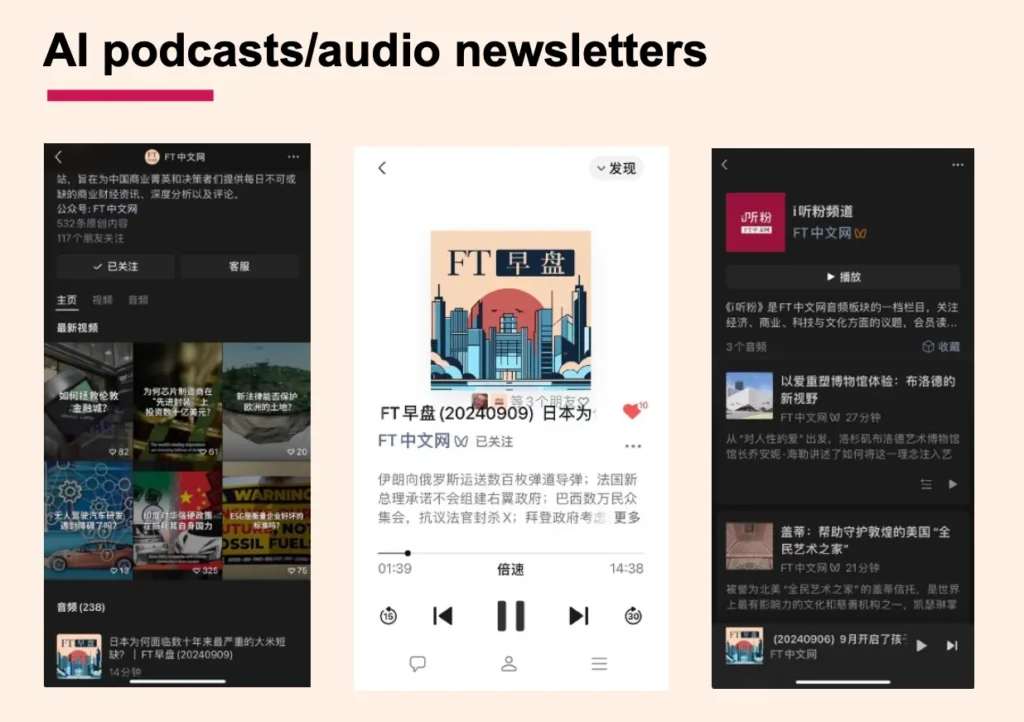

Tian Jian: Aside from ChatFTC, is FT also using AI in podcast production?

Wang: Many of these are still experiments and have not yet been officially launched. For instance, people found it interesting that NotebookLM could create podcasts, but after a few days of using it, they realized it’s not possible to control how issues are discussed, so the final results aren’t good enough to present to readers as a news product. It’s more useful for internal brainstorming. Many AI tools are like that: fun to try, but we haven’t figured out exactly how to apply them yet.

Where FT Chinese has applied AI in its news products more systematically is in voice summaries. For example, turning a 2,000-word article into a 200-word summary, then using an AI voice to read it aloud, and sending it out daily to readers via WeChat. This is useful for drivers or commuters who can listen to articles with their earphones.

I think Chinese readers are very open to new things. They’ve responded very well to AI voice summaries. But I once tested an AI podcast on my personal WeChat account. As soon as readers were told it was just two AI voices talking to each other and was made by AI, their interest declined. So the key is still the added value of humans.

FT Chinese uses AI tools mainly for peripheral tasks, especially on the content distribution side. When producing original content, we still abide by tradition.

Tian Jian: Reporters and editors are responsible for their output. Has FT Chinese ever encountered problems with AI use?

Wang: We haven’t had any scandals or major factual errors. Our internal practice is that original editorial content passes through at least two pairs of eyes. Compared with traditional media, where three or four people review drafts, this may leave more room for error, but so far we haven’t encountered obvious problems.

Currently, FT Chinese uses AI tools mainly for peripheral tasks, especially on the content distribution side. When producing original content, we still abide by tradition: reporters conduct face-to-face or video interviews, record everything, then turn it into text, video, or audio — a very traditional content creation process.

Where does AI fit into this process? For instance, when interviewing an expert in a field we know little about, how can we come up with good questions? This is an area where we will use AI more often. The interview itself is still conducted face-to-face, and what the interviewee says must still be noted and written down by us.

If AI helps with transcription, we still need to verify the content afterward. This process already filters out most inaccuracies or hallucinations that AI might produce. So AI plays a supporting role.

Once we’ve produced the text or video, we can then use AI to further process it — turn it into a newsletter or a podcast. In other words, content is produced through a traditional, verifiable journalistic process, and then it’s further produced or distributed with the help of AI.

Tian Jian: Does this show that journalism as a profession still has value? How do you view today’s flood of AIGC (AI-generated content) online?

Wang: Articles written by AI absolutely cannot be published directly. Even after multiple rounds of editing, we’re not necessarily confident that AI-generated drafts can have accurate journalistic judgment.

Our priority is to ensure as much as possible that in the core workflow of journalism – especially when it comes to originality, accuracy, objectivity, and newsworthiness – there is always human judgment. If we can ensure that, then the resulting content won’t differ much from what traditional processes produce. AI is only used for secondary or tertiary processing, improving efficiency in distribution. This way, we’re less worried about possible inaccuracies.

On YouTube and TikTok, you already see massive amounts of AIGC. Much of it is entertainment or leisure content, with low information value, not much different from the social media “clickbait” era before AIGC. Aside from wasting huge amounts of people’s time and causing “brainrot,” it’s not a major direct harm.

Our priority is to ensure as much as possible that in the core workflow of journalism – especially when it comes to originality, accuracy, objectivity, and newsworthiness – there is always human judgment.

But content that lies between entertainment and news and information, large volumes of AI-generated content that is unverified, contains false or incomplete information, and is spread widely — that can cause serious harm. Political, commercial, or criminal actors can weaponize it for misinformation or disinformation campaigns. The risks are many times greater than in the social media era and are deserving of serious vigilance. Some countries, including China, have already created legislation requiring social and information platforms to label AI-generated or AI-assisted content. I think that helps mitigate the harms that come with AIGC.

Tian Jian: What AI skills should journalists develop? Which AI tools do you most recommend?

Wang: Personally, my favorite is Perplexity. It’s very powerful, and even the free version can already examine a lot of content. For handling large volumes of data, NotebookLM is quite useful, since it ensures no fabrications. At the moment, it’s capable of handling cases like dozens of presentation slides or a few hundred thousand-word manuscripts or academic papers.

Another is Google Pinpoint. I’m still learning it and haven’t found the right opportunity to apply it. My understanding is that it’s well-suited for combing out datasets on the scale of something like the Panama Papers, when you need to sort through and search for leads. But we haven’t had the chance to test this tool with such large datasets yet.

There’s also Manus, currently the only AI tool I personally pay for. It can handle very complex tasks. Recently, I wrote a journalism textbook based on my past two years of teaching part-time at Tsinghua University (in Beijing) and the University of Hong Kong. But I didn’t write it manually: I uploaded 600–700 pages of PowerPoint slides to the AI and used it to write.

I tried many tools, including ChatGPT, DeepSeek, and Manus. After months of trial and error, I worked out a process. First, I had Manus create a clear chapter structure according to the slides, essentially creating the framework of the book. Then I used ChatGPT’s Deep Research function to fact-check, supplement content, and connect the logic within the text. After researching this process, I could write the book much more efficiently.

I give my students two basic principles. First, I encourage them, even require them, to use AI. Because if they don’t, by the time they graduate, everyone else will be using it, and they’ll lack competitiveness. Second, I tell them that they must take responsibility for all content, whether generated by AI or not. If AI produces hallucinations, bias, or inaccuracies, you must be able to detect and correct them.

And how do you detect and correct them? This is why we still need traditional journalism education. You still need to learn today about what journalism was 20 years ago, so you can know what AI gets wrong and what it gets right. Without that, you don’t have the ability to make judgments.

Tian Jian: For students using AI, do you set limits or quotas?

Wang: I don’t set any limits. Using a tool to determine whether 70 percent of an article was written by AI is a foolish task. So-called “AI-detection tools” are unreliable and always lag behind large language models.

Now, many students worry that, even if they wrote their papers themselves, tools may still say it’s “40 percent AI.” So they spend more time worrying about being mistaken for using AI to cheat. That’s completely counterintuitive. So I see no point in restrictions.

My view is: no matter what tools are used, if it’s well-written, that’s great. As long as you can ensure it’s accurate, I’ll give it a good grade.

Tian Jian: What advantages does the growing use of AI and social media among the next generation of journalists and journalism students bring to the profession?

Wang: At Tsinghua, I teach traditional journalism courses, English news writing, and business news writing. But every day I ask my students: where in the classroom could you use AI to be faster? Or, if you’re comparing financial reports from the same company across two years, which tool helps you be more accurate? I use AI tools in this way daily to reinterpret traditional journalism workflows.

AI is particularly helpful for journalists and students like us whose native language isn’t English; it’s particularly useful in helping us master writing style and correct grammar. Over the past two years, I’ve seen students’ writing improve a lot. The content they hand in is quite good. But I can’t be sure how much of that they learned themselves and how many shortcuts were made possible by AI.

I can also be sure that I must teach them how traditional journalism is done, what’s right and what’s wrong, what’s good. Even if you didn’t write it yourself, at the very least, you need the ability to make a judgment. Using AI to help with processing is fine — ideally, you would add your own insight and perspective during the process. Ultimately, the content must be accurate, meet traditional journalistic standards, be good, fresh, and sustainable. If you can do that, it’s enough.

Tian Jian: I’m curious, how do you think Western and Chinese-language media differ in their attitudes toward AI?

Wang: At least from what I’ve seen, journalists and readers in mainland China tend to be more open-minded. Of course, we must ensure everyone recognizes the risks, including the ethical, legal, privacy, and data security problems. But overall, compared with the West, China seems more accepting.

Within FT, I’m personally more cautious. Many of our senior journalists and editors are not so quick to embrace these tools. It’s still a challenge for the company to persuade them to adopt AI more fully.

Tian Jian: You seem curious, experimental, and enthusiastic about new technologies yourself. How about the rest of your FT Chinese team — what’s their general attitude toward AI?

Wang: I am indeed especially interested. I’ve been a journalist for 26 years across wire services, newspapers, and magazines, but for about 20 of those years, I’ve been an editor, mostly working on digital platforms. So I’ve always been something of an internet native, always relaunching websites, building new functions for the website, and adding social media features. Maybe that’s why I’m more open to AI.

To some extent, I influence my students more than my colleagues. For colleagues, all I can say is: “Here’s a process I figured out that will make your work simpler.” For example, when COVID started five years ago, the company carried out major layoffs. Suddenly, our staff had been reduced by a lot, but the workload was just as much as before, and everyone suddenly faced enormous pressure.

Even if you didn’t write it yourself, at the very least, you need the ability to make a judgment.

During that process, I helped them think through ways AI could speed up transcription. I drafted an initial workflow, then we discussed it together so they could see the practical benefits. Otherwise, they would be working 15-hour days. This way, they were more willing to buy in.

I never forced anyone, nor did I set KPIs or deadlines for AI adoption. I just showed them that sticking with the old ways was exhausting, while AI could boost efficiency; is this not a good thing?

Tian Jian: When reporting on China-related topics, how does FT Chinese strike a balance that maintains professionalism and depth, while also ensuring smooth publication? Have you encountered subjects that require extra caution?

Wang: FT Chinese’s mission is to serve China’s business and professional readers with economic, financial, and technology information. This positioning helps us resolve many potential legal, policy, and regulatory issues we may encounter in the Chinese market. At the same time, we emphasize showing the Chinese perspective, inviting many mainland and Greater China experts, scholars, and professionals to write original commentary and analysis. This helps us balance Chinese and Western discourse and provide readers with professional, neutral, and balanced in-depth information.

Tian Jian: On June 28, US financial weekly Barron’s partnered with Chinese financial-tech media TMTPost (鈦媒體 ) to launch Barron’s Chinese (巴倫中文網). How do you view Barron’s strategy to launch Chinese-language content at this moment?

Wang: Barron’s has a competitive relationship with FT, so naturally, Barron’s Chinese will also compete with FT Chinese in both the content and business aspects. Given that many international media platforms’ Mandarin-language sites have shut down or withdrawn from the mainland in recent years, we view other international outlets opening Chinese platforms to serve mainland readers as a positive development.

This interview was translated and edited by Jordyn Haime, with assistance from Claude AI.

Tian Jian