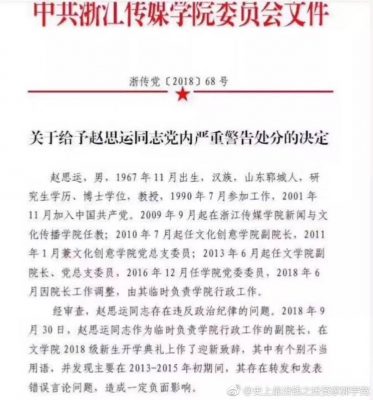

In a report last week, The Paper, an online news site operated by the Shanghai United Media Group, revealed that Zhao Siyun (赵思运), a professor at the Communication University of Zhejiang serving as deputy director of the Academy of Literature, had been issued with a “severe internal-Party warning” (党内严重警告) for a speech he gave in September to incoming students.

According to a university document cited by The Paper, Professor Zhao was being disciplined because his welcome speech to students had “contained violations of political discipline” (政治纪律). As a result of the incident, Zhao’s prior words and conduct were also apparently subjected to greater scrutiny, and the notice alleged (in apparent reference to Zhao’s social media accounts or online speech) that between 2013 and 2015 he had “shared and posted erroneous remarks, creating a negative influence.”

What exactly did Zhao say?

His welcome speech to incoming students focusses broadly on principles of “self-discipline,” “respect,” “dignity” and “responsibility” — none of which would seem unwelcome concepts to instill in young minds. But Zhao’s address links these principles first and foremost to the individual — and independent — agency of the student and intellectual as “living creatures capable of independent thought,” each with their own “completely unique dignity and value.”

Zhao’s masterstroke of political mischief seems to have been his resurrection and definition of the concept of the “public intellectual,” or gonggong zhishifenzi (公共知识分子). This term has become a deeply sensitive one in China over the past decade, and has never in the reform era been more sensitive than it is now under Xi Jinping. Readers may remember that the notion of “civil society,” closely connected to the role of the public intellectual, was explicitly targeted in the so-called “Document 9” in 2013, which even months before Xi’s August speech on ideology that emphasized the supremacy of the “Party spirit” that proponents of civil society “want to squeeze the Party out of leadership of the masses at the local level.”

In his welcome speech, even Zhao notes the sensitivity of the term, saying: “In recent years, the idea of ‘the public intellectual’ has been stigmatized, and there is a need for us to get back to the roots of this concept.”

At the root of Zhao’s failure of “political discipline” is the notion (so threatening to the Party) that the intellectual, that the thinking mind, owes its allegiance primarily to independent conscience of the individual — that the intellectual finds self-respect and dignity in knowing her own mind in relation to society, and in applying her knowledge and conscience to the betterment of that society.

As a matter of immediate context, we should remember that the Party’s own discipline regulations, recently revised with an emphasis on Xi Jinping and the centrality of his leadership, put the Party itself as the heart of discipline. What the Party demands is loyalty. Dignity? The only ideas that will be dignified are those that serve the interests of the Party, and of Xi Jinping as the Party’s “core.”

We include a partial translation of Zhao Siyun’s welcome speech below.

Readers may note that there are various versions of the story of the death of translator Fu Lei and his wife, Zhu Meifu, at the outset of the Cultural Revolution. In his speech, Zhao returns to this image of the couple as symbols of love and partnership, but also of deep and unshakeable conscience, refusing “vulgar compromise.”

The Public Intellectual is a Scarce Resource

By Zhao Siyun (赵思运) / September 30, 2018

Beloved classmates, and respected teachers, good morning!

I’m really delighted that at the right time, in the right place, we have all the right people here! On behalf of the Academy of Literature (文学院), I offer the warmest congratulations and welcome to all of you who have come today!

Everyone has had a look around already, and all of us here are from the Academy of Literature! But what especially makes me happy today is to look out and see in your faces so thirsty for knowledge my own younger self. Allow me in the name of youth to take this opportunity to speak my heart.

Each year when new students arrive, parents will pull teachers, class heads or leaders aside and say: “We leave our children in your hands!” This is about trust, about great trust, and I thank everyone for the trust they have placed in the Academy of Literature. However, from another perspective, it’s as though you are household “valuables” that have been placed from your family hands into the school’s hands. What I want to say is that you do not belong to your parents, and you do not belong to the school. You are living creatures capable of independent thought (独立思考), and you each have your own completely unique dignity and value. Your parents watch you grow, and your teachers watch you grow. Your parents have been your left hand, and your teachers have been your right hand. Now, 18 years of age, you are entering the university campus, and beginning your own independent journey in life. From here on out, you will begin to find maturity. The first sign of maturity is “self-discipline” (自律). This is the first keyword I would like to discuss with everyone today.

Self-discipline is a form of cultural conditioning. This process of education comes through the details of daily life. We can carry out self-examination: When others pour water for me, do I support them with my own hand as a way of showing respect? When I offer drink or food or wine to others, do I do so with both hands? When I am the last to enter through the door, do I remember to close the door behind me? When I ask a question to my teacher, should I stand first? Look again at the classmates all around you. Haven’t we had classmates that already within five minutes have gone off to the toilet as though no one else is around them? Or classmates who just before class is about to finish will just head off for the toilet as though no one else is around? Let us remember: a person capable of self-examination, and who is full of self-restraint, has real spiritual strength!

Let me talk next about respect and dignity. We are all equal in life, and we have inviolable dignity. Therefore, people should uphold mutual respect between one another. During Teacher’s Day this year, a student I taught during my first year of teaching, Qin Xulin (秦绪林), sent me a poem that he wrote, and in this poem he talked about how one day he went to my office to seek my input on something, and he felt a sense of “equality” and “respect” between teacher and student. From his description of our exchange, I get a deep sense of how a teacher must maintain an attitude of equality and mutual respect.

King Edward [VIII] of England once went visiting among the poor in London, and he stood in the doorway of a dilapidated house and said to penniless old man inside: “May I come in?” This demonstrated his respect for those at the lower strata of society. We might even witness greatness in the person of a female prisoner. On January 21, 1793, as one female prisoner was led up to the guillotine at the Place de la Concorde in Paris, she inadvertently stepped on the foot of her executioner, and immediately she spouted out: “Pardon me, sir.” I was really moved by that story. And I would say that that female prisoner showed “greatness.”

We could look also at the famous translator [of Balzac into Chinese] Fu Lei (傅雷). On September 2, 1966, after two days and three nights of incessant humiliation at the hands of Red Guards, the translator Fu Lei was, “like the silent prophet, or the solitary lion, resentful and proud, never stooping to vulgar compromise or bowing his head” (in the words of his son, Fu Cong). For the sake of dignity, on that night, he and his wife Zhu Meifu (朱梅馥) went hand-in-hand to death inside their house on Shanghai’s Jiangsu Road. Zhu Meifu prepared warm water so that Fu Lei could ingest his poison. In order to preserve Fu Lei’s dignity, Zhu Meifu propped him gently on the sofa, and then herself ripped up the bedsheets to make a noose with which to hand herself. She was 53 years old. In order to ensure that the sound of her kicking away the stool would not wake the neighbors, they first spread a quilt out on the floor. Then, quietly, they went . . . .

But very often we grow estranged from our sense of “respect” and “dignity.” Over the summer this year, I saw in my neighborhood a repairman working under the blazing sun. I said to him respectfully: “You’re working hard!” He didn’t respond. I said more loudly this time: “You’re working hard!” This time, he raised his head and gave me a look of acknowledgement, but still said nothing. After I had passed, I heard him behind me saying under his breath: “Does that guy think I’m someone he knows?” That’s right, self-respect and conducting oneself with dignity are valuable points of character. Respecting others begins with respect for oneself; it begins with the discovery of one’s own dignity. As teachers and students in the Academy of Literature, we must always seek out respect for life, must seek out the meaning of life, and we must protect our integrity and dignity.

The third issue I want to discuss with you is the way personal dignity and the vigor of our national character (国家民族的担当) are closely linked together. As university students in the New Era, you must take responsibility for the future of the country and our people. The famous scholar Ge Zhaoguang (葛兆光) said recently: “Our university system today is giving rise to a generation of people who tend toward their specializations but have no care for their society.” Peking University professor Qian Liqun (钱理群) hit the crux of the issues a few years ago when he said: “Chinese universities are raising a mass of pure egoists (精致的利己主义者).” On this note, I call on you — to carry on the great tradition of intellectuals: “In my ears are the sounds of wind, rain and reading; but my heart cares for the affairs of home, country and people.” I call on you — to rebuild the belief in “public values” (公共价值) among intellectuals.

In recent years, the idea of “the public intellectual” (公共知识分子) has been stigmatized, and there is a need for us to get back to the roots of this concept. The precise sense of the “public intellectual” is someone knowledgeable who has a background in scholarship and professionalism; someone who offers advice to society and who takes action in public affairs; an idealist who is vested with a critical spirit and a sense of nerve and justness. This right now is a spiritual resource that is scarce. Social responsibility is a sense of responsibility for the entire public, and it is required of each and every one of us, so that no one can find any reason to choose silence. There is a very good saying that goes like this: “To let everyone know the facts you know is to have justice; to share your understanding with everyone is to have responsibility; to tell everyone of the wickedness you have witnessed is to have conscience; to tell everyone the truth you understand is to have morals; to warn everyone of the lies you hear is to have fraternity . . . . ” Only those who have a deep and abiding love for their country and their people will criticize the darker aspects of their society. Only those who cherish the light will go and expose the vile corners of life. Because they know that this is their responsibility, that it is the bounden duty of the modern citizen! These days, we see every day how people online throw out curses about “bad people are getting old” (坏人变老了) — [NOTE: This is a popular online phrase about elderly people forcing courtesy on the young, such as making them give up train seats that are legitimately theirs] — but we should caution ourselves and wonder whether in years to come future generations might curse us in exactly the same way, saying that “bad people are getting old!” I also want to say that justice isn’t about just complaining and letting off steam. Primitive justice may be precious, but true justice is justice built on reason and law.

. . . .