Fandoms and “Digital Labor” in China

Joyce Chan

Yiyi Yin

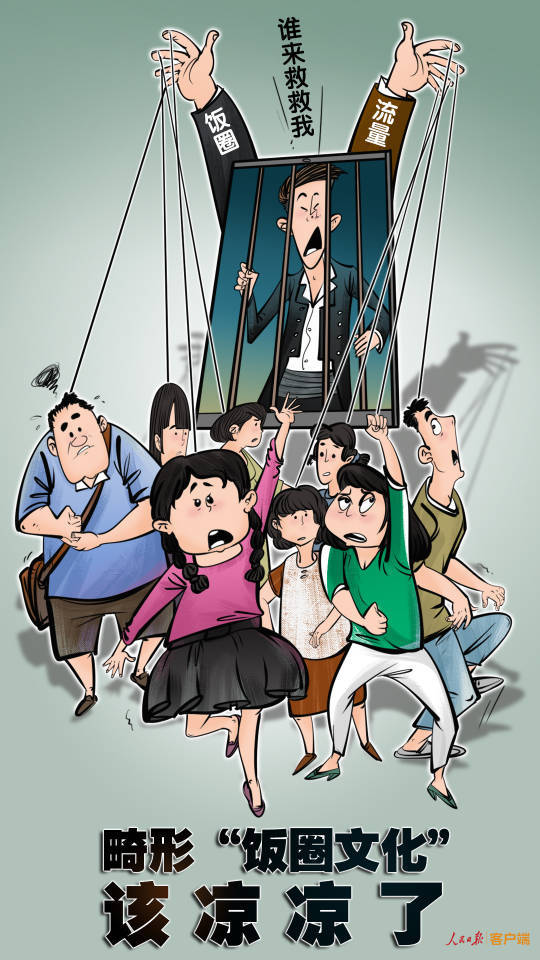

The Trouble With Fandoms

Joyce Chan: Fandom culture recently became a new target of the Cyberspace Administration of China (10-point guidelines published on 27 August), because of celebrity scandals and fan community cultures that are seen to be overstepping boundaries. Could you briefly explain the rationale behind this? Why are fandoms seen as a problem?

Yiyi Yin: This was not the first time a fandom-related policy was released. In the past few years, online fandoms have been portrayed by the state and media as a source of trouble, and thus recognized by the public as such. Several socially influential cases happened, including the conflict between celebrity fans and the site AO3 (227 incident), and more recently the case of Kris Wu and Zhehan Zhang.

Cases like these led directly to the adoption of the policy, which should not be understood simply as a regulation of fandom, but more generally of the whole internet sphere, and of capital expansion of both internet companies and the entertainment industry. In other words, the current regulation is in fact targeting more on the platforms, celebrities, and entertainment companies, rather than merely on fans.

Joyce Chan: In your paper, you talk about “emotional capitalism” and “emotional labor” when you write about fandoms. Could you explain for our readers how fandoms in China work, and how you see these concepts applying to Chinese fandom in particular?

Yiyi Yin: It’s quite complicated to explain. In general, we see fans often contributing, first of all, to the public image or popularity of the so-called idols, celebrities or fan objects. Secondly, the material profits benefiting the fan objects. Their contribution was based on the affective intimacy, [a perception of closeness and emotional bonding], that was both imagined and manifested in fan practices. In one sense, the capitalization of fandom was facilitated and legitimated by this kind of affective intimacy or the affective para-social relationship between fans and the fan objects.

In China, digital labor was constructed as an efficient way to actualize or manifest this affective relationship, as the data itself has become an “object” relating fans’ affective pursuit and the celebrities who were not actually accessible offline.

Joyce Chan: Just to clarify, the term “digital labor” refers to the often-unpaid work of social media users creating value by generating interaction with idols. Is that correct? And are there any figures available to indicate the level of economic activity that has been created in recent years by the relationship between fans and their idols?

Yiyi Yin: I would define digital labor as the often-unpaid work of social media users creating value by patterned use of digital media, and in the case of fandom, this patterned way of media use is legitimated affectively by the interaction or imaginary interaction between fans and idols. I don’t think I have any figures indicating the level of digital labor or its generated economic activity, but you might be able to find some useful data in the annual reports on entertainment industry. Tencent publishes an Entertainment White Paper (娱乐白皮书) every year, and I believe they have included some reports on fandoms.

The Social Impact of Fandoms

Joyce Chan: Moving on to the social impact of fandom culture, it seems clear from several cases in recent years that fandoms have been highly organized communities. And they’ve mobilized around a lot of issues beyond just favored idols. For example, around aid for the fight against Covid. Could you speak briefly about the organizational power of fandoms?

Yiyi Yin: One reason is because the fan community is usually mobilized affectively. It gains organizational and activist power from affective identifications and enthusiastic love. They consider the collective fan practices, including fan-cheering, collective purchasing and helping the fight against Covid-19 as the embodied practice manifesting the imaginative intimacy between them and the idols. Some of these practices both favored the idols and the public, while others might only favor the idols and relevant actors – for example, purchases and so on.

The fan organization has a long history going back to the 1980s and has developed to be more organizational, facilitated by the Internet and social media platforms like Weibo. Weibo serves as a very important platform for Chinese online fan culture, as it enables different fan communities and fandoms to be connected and visible to the public. This kind of visibility and connectivity influences the organizational structure of fandoms and how they mobilize themselves to perform in front of the public in some way. I would say the organizational power of fans is sometimes performative as well.

“I would define digital labor as the often-unpaid work of social media users creating value by patterned use of digital media, and in the case of fandom, this patterned way of media use is legitimated affectively by the interaction or imaginary interaction between fans and idols.”

Joyce Chan: When you say that the power of fans is “performative,” what exactly do you mean by that? Could you provide an example of how this works in practice?

Yiyi Yin: Fans sometimes mobilized themselves to “perform” the good public image of the celebrity. For example, in the case of Covid-19, fans donated under the name of an idol primarily to contribute to the reputation of the celebrity. In this case, the primary significance of their actions is not always about the political or social good, but about the visibility of the celebrity, as in how the online public would perceive the celebrities because of their acts. If we consider fan practice as a form of performance, then the prediction and the attempt to control visibility serve as a significant rationale for their acts.

Joyce Chan: Could you describe the fan practices that are characteristic of such fandom groups? Are the groups now banned from continuing these practices due to the “purification” of the online atmosphere on various platforms?

Yiyi Yin: As I described in my article, digital labor has become a daily practice for many celebrity fans. Besides voting as a ritualized practice, their digital practices include “comment spamming” (控评), “anti-trolling” (反黑), and “formatting postings” that would be counted towards traffic data and that can boost the online visibility of the celebrity. These digital labors have often been organized and motivated by the social media platform logic that is driven by traffic data.

For now, the groups are not technically banned. Nevertheless, since the regulation targets platform rules in terms of traffic generation, some of the digital practices might be restricted. For fans, however, this is not necessarily a bad thing, since they didn’t actually enjoy carrying out the practices in the first place. The acts of digital labor were dictated by the platform infrastructure, and fans had no choice but to accept the affective power attached to them.

Joyce Chan: It’s interesting that you describe voting here as a “ritualized practice.” Could you explain what you mean by that? How does it play a role in social media algorithms for fandoms?

Yiyi Yin: Traditional voting takes place through a competition, which only lasts for several months and leads to a result with significant titles. In voting, fans have to organize themselves as a sort of working group or voting group to participate in the particular competition. This is how the voting has been ritualized.

However, in the algorithmic fan culture, digital labor has become embedded into the everyday practice of online fans. They don’t need to join any group or take serious tasks to complete the voting, but only need to post in particular formats or sign in to Weibo every day. The data contribution has been routinized in common fan practice and even common media use. For fans, this is how they use social media platforms.

Joyce Chan: If we can turn for a moment to the topic of fandom nationalism. Can you tell us how the development of fandom nationalism, exemplified by the construct of “Brother A-Zhong” (阿中哥) – a kind of idolization of the Chinese nation – and Diba Expeditions, has influenced the overall dynamic of fandom culture on Chinese social media?

Yiyi Yin: I am not an expert on fan nationalism, so I might not be able to answer the question profoundly. I would say the development of online nationalism might influence the atmosphere of the internet sphere more broadly, rather than only fan cultures. It’s also a tricky thing to equalize the “fans” of Brother A-Zhong and fans in the Diba cases to the fans or celebrity fans we discussed in other questions. The “fandomization” (the appropriation of fan practices) and the rise of online nationalism can be considered as parallel in the internet sphere in China.

Joyce Chan: Does the rise of fandom nationalism concern the authorities in China? It certainly seems to have been a rather grassroots, even to some extent democratic, phenomenon. Is that a concern now?

Yiyi Yin: Again, I’m not an expert regarding this topic, but from what I know, the rise of fandom nationalism has become a kind of mobilized power that concerns the authorities. There have been cases that the social media account of Communist Youth League tried to announce virtual idols to mobilize “mainstream” fans.

Joyce Chan: So, what impact do you think the new rules about fandom culture will have on fandoms in China?

Yiyi Yin: So far, I would say there are some good signs especially in terms of platform regulation. The new rules have shut down platform league tables, which somewhat “released” the fans from the ongoing practice of digital labor. The online visibility of fandoms decreased as well, which I believe might be a protection rather than a restriction of fan culture. Nevertheless, as fandoms have concerned the authorities increasingly, fandoms, especially celebrity fandoms, will probably become more “mainstream” in the future.

Joyce Chan: That sounds quite unexpected and even counterintuitive. Can you elaborate a bit more on the logic that while platform regulations decrease online visibility of fans, fandoms would become “more mainstream” in the future? What do you mean by this?

Yiyi Yin: As I mentioned, the attempt to control the visibility of celebrity, such as preventing negative rumors or news of the celebrity to appear in the trending list; or increasing the visibility of the positive public image of idols by donating materials to Wuhan in the case of Covid, is the significant rationale underlying online fan practices in China. In this process, fans have to compete with other participants on social media platforms such as fans of competitors, the digital media, entertainment reporters and so on.

To some extent, fans have no choice but to take part in this game of visibility, otherwise they would lose control of the visibility of their idols’ public images. This is exactly how emotional capitalism works, since the social media platform sometimes convinces the fans that the consequence of losing visibility could be miserable, like by protecting or promoting certain digital media accounts that routinely spread false rumors. Therefore, for fandom specifically, the regulation indicates an “authoritative” selection of visibility.

As the new policy cuts off the visibility of celebrity and digital fandoms by removing several league tables and trending topic rankings, visibility in this sense would no longer be “controlled” by the platform, but by the authorities. Consequently, fans on the one hand wouldn’t need to compete against others for visibility, on the other hand they would have to act more “mainstream” as a “societally positive community” when they find themselves in the public eye. [Editor’s Note: “Societally positive” here refers to the government-sanctioned positive moral values, which the authorities wish to put in place through the new regulations. “Mainstream” in this context refers to values in line with official frames, just as “mainstream media” in a Chinese context refers specifically to Party-state media.]

Joyce Chan: Do you foresee the fandom community resisting the regulations in some way or trying to alter the mechanisms placed on social media platforms, given their demonstrated creativity as been described in your journal article, “An Emergent Algorithmic Culture: the Data-ization of Online Fandom in China“?

Yiyi Yin: I would say that fans will find their own way to survive, which is why I insisted that fan groups would not be banned or disappear. Fans have been highly creative and flexible individuals, who would participate in affective practices in multiple ways.

Since the offline era, fans often traveled from one site to another, developing creative ways to manifest, embody and actualize their affect. I would say that the current regulation would largely influence the forms and rules of digital fan practices, but would not dismiss the fan culture. Fans might not directly resist the regulation, but they will find ways to negotiate and live with it. This is how fan culture has always been shifting.

Joyce Chan